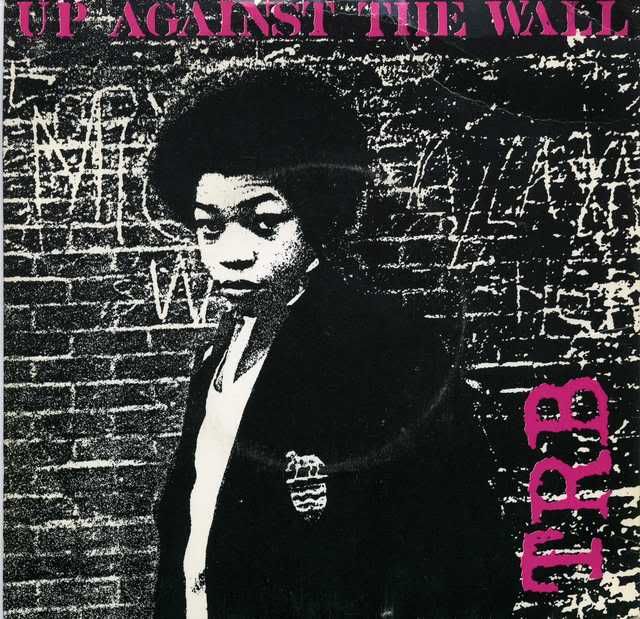

Absolutely thumping third 7″single from T.R.B. both sides that could have been written for the state of society and the labour goverment in 2008, let alone the state of society and the labour goverment in 1978, exactly thirty years ago.

Tom Robinson jettisonned his band Cafe Society after he attended a Sex Pistols gig and got to work on a band that what would become the overtly political T.R.B.

Storming stuff from a great band.

The debut 7″ single from Jam Today, a hardcore lesbian -feminist band mentioned by Tom Robinson in the excellent N.M.E. article below can be found on this site if you use the search function.

NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS – February 11 1978

By Phil McNeill

Pictures of naked young women are fun

In Titbits and Playboy, page three of The Sun

There’s no nudes in Gay News, our one magazine,

But they still find ways to call it obscene . . .

Long before Mary Whitehouse ever discovered the hideous charge if ‘blasphemous libel’ on which she spiked Gay News last year, the vigilante forces of our nation had worked out another method of hurting Europe’s foremost homosexual newspaper. If anything, it was even more slimy than Whitehouse’s tactic. See, Gay News has always been most careful to stay within the highly flexible limits of the laws governing obscenity. Like the song says, no nudes, no porn, no sensationalism. No way could GN be found to contravene the Obscene Publications law. But – and this was the BIG but that the authorities latched onto sometime around 1974 – just because a paper isn’t obscene doesn’t mean you can’t take it to court. It may come out of the case innocent, but the British courts have a clever way of fining the innocent: LEGAL COSTS.

Twice in 1974 GN fell victim to the British legal system. Police swooped on newsagents in Bath and some other south coast town, took the paper to court – and the judge, although deeming the magazine innocent, refused to award legal costs, thus depriving it of the several thousand pounds required to mount its defence against the police’s rejected charges. It was at a benefit to raise funds for one of these Gay News legal battles that I first saw Tom Robinson. The venue was the Royal Mail pub in Upper Street, Islington, the date late 1974. A typically jolly gay get-together it was. GN editor Denis Lemon – already a hero and potential martyr to the people there – blushingly handed out the prizes in the raffle, and then, to fill the gap before the headlining drag queen made her entrance, a pallid youth got up on the stage and diffidently strummed out a totally unmemorable little ditty he’d just penned.

That young man, of course, was Tom Robinson. If you’d told me then that three years later he would be leading one of the fiercest rock ‘n’ roll bands in the country, you would have been laughed out the door. So how did he get from sentimental acoustic love songs to Whitehall-up-against-the-wall? The glib answer would be; money. It would be very easy to accuse Tom Robinson of jumping onto a political slogan bandwagon just as the whole ‘movement’ gathered impetus in late ’76 – and people have already done so. One of those people, who has known Tom for five years now, is Ray Davies.

A well known groover, rock ‘n’ roll user,

Wanted to be a star.

But he failed the blues, and he’s back to loser,

Playing folk in a cafe bar.

Reggae music didn’t seem to satisfy his needs.

He couldn’t handle modern jazz,

‘Cause they play it in difficult keys.

But now he’s found a music he can call his own,

Some people call it junk, but he don’t care,

He’s found a home.He’s the prince of the punks and he’s finally made it,

Thinks he looks cool but his act is dated.

He acts working class but it’s all boloney,

He’s really middle class and he’s just a phony.

He acts tough but it’s just a front,

The prince of the punks.He tried to be gay, but it just didn’t pay,

So he bought a motorbike instead.

He failed at funk, so he became a punk,

‘Cause he thought he’d make a little more bread.

He’s been through all of the changes,

From rock opera to Mantovani.

Now he wears a swastika badge

And leather boots up past his knees.

He’s much too old at twenty-eight,

But he thinks he’s seventeen,

He thinks he’s a stud,

But I think he looks more like a queen.He’s the prince of the punks and he’s finally made it,

Thinks he looks cool but his act is dated.

He talks like a cockney but it’s all boloney,

He’s really middle class and he’s just a phony.

He acts tough but it’s just a front

The prince of the punks

Thus spake Uncle Ray on the B-side of his recent seasonal opus, ‘Father Christmas’. Sure, it could be applied to most current bandwagon jumpers – indeed, Ray denies that it was written with Tom in mind – except that Robinson is generally believed to be 28 (he’s actually 27), he does have a motorbike, he is gay, he did use to sing in a coffee bar (Café Society had a residency at Bunjies when they first signed to Konk), he is middle class, he does adopt a Cockney accent for a couple of songs . . . and he does want to be a star. Oh yes – and here’s the rub – he’s finally made it too. Even among TRB admirers, the question nags; what the hell was Tom Robinson doing in that wimpy band all those years? How come he’s only just started playing hard, committed rock in the past year? So . . . what I’d like to do is explain why Tom was in a basically heterosexual band in the first place, to counter some of the more disdainful write-offs of Café Society that have gone down in recent Tom Robinson interviews, and to trace Robinson’s path from indifference to dedicated activism and (as he would claim) back to non-activity.

A very rough chronology: Tom Robinson met Ray Doyle and Hereward Kaye in Middlesbrough around 1969/70. Tom ‘came out’ around 1971/72. Café Society was formed in 1973 after a reunion with Doyle and Kaye in London. His first ‘political’ act was to work at Gay Switchboard, which he did from early ’74 to late ’75. In other words, although he was openly homosexual by the time he formed Cafe Society, he was not ‘politicised’. By the time he was, his career with Café Society was well underway. Being a gay activist began virtually as a hobby, and at first had little or no relevance to his ‘day job’. Maybe this calls into question Robinson’s increasingly frantic ‘commitment’ – coinciding as it has done with his increased success – but I think not. In fact, if we pry into Tom Robinson’s past we see a remarkably clear-cut path of self-realisation and action.

Early in 1975 he did his first ever interview. It was in Gay News.

Q: What do you see as your responsibility within the gay movement?

A: Just to be openly that I think. If every gay in Britain were to come out overnight, an awful lot of the prejudice and ignorance that abounds among hets would disappear. This is a thing that so many people don’t realise about coming out. They imagine that if they come out people will think they’re a ‘nasty queer’, whereas in fact when one comes out with one’s friends they change their idea of what a ‘nasty queer’ is. A lot of people rationalise their fears about coming out. They say they’d lose their job or it would hurt their friends too much. One has to be very scrupulously honest with oneself to make sure one’s not making excuses. I was lucky in that I have a very tolerant father, who is heartily in favour of all forms of sexuality except asexuality.

Q: There are always times – when one meets someone on a train, say – when it would be so much easier not to come out to them. Do you have that sort of experience?

A: Yes, there are always occasions when one does find oneself passing (‘passing for straight’ being opposite of ‘coming out of the closet’). I wonder if there is such a thing as a totally come-out person? I expect there is . . .

Tom Robinson has since become such ‘a totally come-out person’ that he now says that he is “an ‘Uncle Tom’. I’m a straight man’s homosexual . . . a lone homosexual in straight circles.” In passing – we happened to be talking about a song from TRB’s new EP, ‘Right On Sister’, and in what ways men could or could not support women’s rights – Tom told me recently that he would “deeply resent a heterosexual writing about what it’s like to be a male homosexual.” I’m already aware of the trap, having encountered a bit of flak for supposedly patronising women whilst criticising the Stranglers’ sexism on ‘Rattus Norvegicus’. All the same, I reckon it’s possible for anyone to think about major personal ‘confessions’ from their own lives, then to consider the stigma attached to homosexuality – after all, it’s only ten years since it was illegal! – and begin to appreciate the pressures on gays not to come out. Hopefully this may go some way to explain why when Tom first joined Café Society he was apparently prepared to sublimate his sexuality in a group format, rather than storm the barricades from the first minute he registered with an oppressed minority. (“Registering’ is actually the telling appellation Tom gives to his decision to become a member of the CHE – the Campaign for Homosexual Equality.) And then of course, there was Café Society’s music – which was actually very good. I interviewed Tom for ‘Let It Rock’ in June 1975, and asked him then if he might not be happier in ‘an all-gay band’. “I suppose I might consider it,’ he replied, “but they’d have to be incredible, because I really believe in Café Society.”

At that time Café Society were, I guess, at about the peak of their blighted career. Their sole album had just been released; everything before them led up to it, subsequent events lust led down. From the start, Café Society were an imaginative, ‘professional’ trio. The demo tape they cut for Ray Davies – the one that persuaded him to sign them early in ’74 – contained a couple of the songs that would finish up on their debut album 18 months later. Even at that early stage, the crafted harmonies that gave the band its principal raison d’etre were inch-perfect. The album is still good. On the inner sleeve, each member wrote a note about another: Tom on Raphael, Ray on Hereward, Hereward on Tom.

“I sing the song of my friend Tom

Getting ready for his evening cruise

He looks askance in his baggy pants

And sparkling tennis shoes

He grabs his scarf and his other half

And they’re gone before there’s time to glance

‘Cos it’s Friday night and tonight’s the night

They go to King’s Cross to dance

On a silent shelf there’s a photo of himself

And harmonicas from A to G

A reel-to-reel, an A.S. Neil

And a letter to the NME.”

They were a sentimental band. Ray: “Hereward is a top hat and a rose, a mask and a melody, a song and a smile. He’s corny – we should all be so lucky.” Top hat and rose indeed – there was a real corny side to Café, a penchant for music hall which came out in their one single, ‘The Whitby Two-Step’, and which is still uncomfortably prevalent in TRB’s ‘Martin’. But Ray, as Tom put it, “sang with a frightening intensity”. A great singer, with a lovely, warm rasp to his voice. Combined with Hereward’s lyrical passion and Tom’s deft arrangements, it made for an album, which deserved to sell considerably more than the derisory 600 copies it finally shifted. Robinson was more impatient than the others – though none of them speak too highly of Ray Davies and Konk’s record (or lack of – they eventually bust up because the second album never looked like seeing the light of day). Had more Café Society products actually crept onto the market, the band might still be together, and the Tom Robinson Band might not exist.

On the other hand, Tom’s entry into the world of sexual politics definitely caused a certain amount of aggro in Café Society. At the same time as he gradually became frustrated within the confines of a band he now terms “great, but hopelessly ‘60s”, so Kay and Doyle became irritated by Tom’s attempts to inject gay content into the stage act. He now compares their feelings then to how he would feel if one of his band was a health food freak who insisted on singing songs about the evils of white bread . . . The first real infiltration of gay matter into Café’s material was, in fact, quite absurd. Soon after he first started working with Gay Switchboard, Robinson became involved with Gay Representation Action Group, who wanted to get a radio programme together for gay people. Tom wrote a jolly little jingle for the show – which, as far as I’m aware, never reached the airwaves – and somehow it got into Café’s set.

Audiences for the likes of The Kinks, Barclay James Harvest and Leo Sayer – all of whom the trio supported on tour – would blink with amazement when the three guys strumming guitars would suddenly gather at the mike and croon;

“If you’re down in London town and happen to be gay

There’s a great information service open every day

It will tell you who and where and when and how and why and more

On eight three double seven three two four.”

End of jingle. The Gay Switchboard number, incidentally, is still the same. Perhaps, understandably, the bigger the audience they played it to, the more embarrassed the other two began to feel. As it happens, the jingle did get played on the radio. “Kenny Everett played it once,” grins Tom, “and for an hour afterwards Gay Switchboard was swamped with calls with the answer to the Capital Radio Competition.”

But let us digress to Gay Switchboard. Up till his stint with them, Tom’s only gay ‘involvement’ had been to attend a few discos. Then a friend casually invited him to come over and see what went on, and Tom decided to join in. “I was just an ordinary volunteer,” he recalls, “It’s in King’s Cross – this office with three phones and two or three volunteers on a shift.” Tom used to work an afternoon a week. “The phones were just manned 24 hours a day. You’d get these calls in the middle of the night saying (adopts deep Scottish voice); ‘I’m in Abercrombie, and I think I’m a lesbian’ (laughs) – or somebody in Hampstead police station who’d just been arrested. You were like the ambulance service to the front lines. You really saw what was going on at the front, in the daily lives of ordinary homosexuals right across the country. There were calls from people who’d never spoken to another gay person in their lives . . . a lot of silent calls. The phone would ring, and they wouldn’t say anything, but they wouldn’t hang up either. You’d just talk to them, constantly, reassuringly, until you got them to talk. I always used to do that because that was what you were told to do – just on faith – until the first time I actually persuaded somebody to talk after five minutes. After that it was just a natural thing, because there really was somebody at the other end. Or you’d ask them to tap the phone so you’d know there was somebody there, listening. Terrified people all across the country calling you.”

Even so, Tom Robinson still wasn’t angry. I remind him of that first time I saw him, the GN benefit gig at the Royal Mail, and he laughs at how innocent he used to be. “Jesus, yes – I remember it well. But it all felt like a bit of a game, it all felt rather jolly. I don’t really feel . . . (punches fist into palm) this means you – and this means your teeth . . .” Ah, no. The younger Robinson was a man who really did feel ‘Glad To Be Gay’. The song by that title on the new TRB EP is actually ‘GTBG Part II’, or ‘(Sing If) You’re Glad To Be Gay’ – and it was written in direct response to ‘GTBG Part I’.

A typically infectious number, it was written specifically for the CHE Conference in Sheffield in 1975. “A jolly little sing-along calypso,” Robinsons spits contemptuously. “’A natural fact – it’s good to be gay’! And I really believed it!” Over the course of the next 12 months, Robinson discovered that people really did mind if you were ‘honest and gay’, and that rather than ‘prefer you that way’, they’d prefer you either locked up or hospitalised. “A year later I’d been thoroughly disillusioned not only by the apathy of the gay movement itself, but by the things that were being thrown at us as the gradual clampdown and the backlash came. “A year later I wrote, (Sing If) You’re Glad To Be Gay’ as a reaction against my own naivety in writing ‘Glad To Be Gay Part 1’. I’m sure I’ve gone down in print saying this lots of times before, and I’ll probably end up quoting myself, but we had fascist editorials – there’s no other word for it – in the Sunday Express and the Telegraph, about ‘The Buggers’ Charter of 1967’, and the People writing stories about vicars and scoutmasters with monotonous regularity during the early part of ‘76 . . . We had the Peter Wells case. Peter Wells was sent to prison for two years for having sex with a consenting 18-year-old – at 18 you’re meant to be an adult, man. You’re allowed to vote, kill, buy a house, get a mortgage – you can do anything except go to bed with another guy.”

Beginning to sound unnaturally like a politician even in the confines of his dowdy little Highgate bed-sitter, Tom runs on through the list. “One of my best friends, David Seligman from gay Switchboard, got beaten up by queer-bashers. His face is still scarred even now. Incognito, which is a gay publishing chain, got busted, and its shops were closed down. Okay, Incognito published a bunch of sexist shit, but they were busted because it was gay. By the time of Gay Pride Week, at the beginning of August 1976, Robinson was transformed. During that week, he staged his solo ‘Robinson Cruising’ shows for four nights at the Little Theatre, St Martins Lane, receiving an approving, sensitive NME review from Penny Reel (who, interestingly, recently remarked to me that he found the TRB’s sloganeering style trite and outdated). For that performance, Robinson would sing ‘Glad To Be Gay’, then reel off a list of gay clubs and pubs whilst a stooge in the audience hollered out the fate that had recently befallen each one of them: “closed – closed – busted – closed – busted – busted – closed . . .” Tom’s ire was not lessened by what he saw as his brothers’ and sisters’ apathy in the face of the backlash, retreating placidly to whatever new boundary the law chose to ring around them. He would then perform ‘Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay’.

Written initially as a venomous send-up of male homosexual complacency, with a verse (since deleted) referring specifically to Peter Wells, ‘Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay’ is both misinterpreted and completely bizarre when it’s yelled out lustily by a predominantly het TRB audience. “Yes, very bizarre,” Tom agrees. “It was on the strength of the thing as a song rather than who it was for or about, that it ended up in the set. Now it would be a sell-out not to play it. I don’t know how I feel about hearing 2,000 heterosexuals singing it at the Lyceum. I have very serious reservations about it. I don’t know how I feel about going to play in Middlesbrough, and I see all these butch young men who are either working down the docks or the steel works or unemployed, who I used to be in terror of having my head kicked in by when I used to live there, standing there waving their scarves, going, ‘SING IF YOU’RE . . .’ I don’t know how I feel about that. All the time I lived in Middlesbrough I was terrified out of my life, in case anyone found out I was gay . . .”

Apart from the anti-homosexual backlash over that year, ’75-76, the other major influence on converting Tom Robinson from passive pride to militant action was a New York theatre group called Hot Peaches. A radical, outrageous drag show, their leader Jimmy Centola became a firm friend of Robinson’s – indeed, he guested on the Robinson Cruising shows – and it was his brash drag queen approach that pushed Tom out of his previous laidback ‘cool’ stance into fist-brandishing anger. “Apathy ruled that summer,” Robinson recalls. “Still does, come to that.” The Hot Peaches came over to do a week’s stint at the ICA. They needed a guitarist, and Tom was enlisted . . . “It was just sweltering in the theatre – people had their shirts off – and every night there was another riot down at the Colherne. While we were playing, the news was filtering back. That’s when I wrote ‘Long Hot Summer’ – a gay street-fighting song.” Its inspiration was taken from a Jimmy Centola rap/poem, in which he would describe the events, which took place at Stonewall, New York, one night in 1969 – the gay world’s most famous riot.

Robinson spits this out now, word for word – he has an amazing memory – to illustrate Centola’s straight-ahead, shocking, audience-confrontation approach. I never saw Hot Peaches, but according to Tom they would stun even the most upfront gay into a new self-pride. Again written principally for gay consumption, ‘Long Hot Summer’ actually found its way into Café Society’s set towards the end of Tom’s sojourn with the trio. Indeed, its easy flow matched that group as irresistibly as its tension now matches TRB.

That song was first unveiled during the Robinson Cruising Gay Pride Week shows – when Tom’s band included, incidentally, Café’s Ray Doyle and a guy who would later play guitar in an early incantation of the Tom Robinson Band, Roy Butterfield (a.k.a. Anton Mauve). It must have struck an ironic note, with its call to resist police harassment, because the Gay Pride Rally, which climaxed the week was Apparently governed with an iron fist by the friendly Bobbies.

A swift drive through the cross-town traffic to a Queensway Chinese restaurant, and Tom describes the events of that day. We’re actually discussing the compromises Gay News makes in terms of toning down its content to get a place on W.H. Smith’s racks. Tom defending it staunchly against those gays who put it down – “They’re as stupid as Mary Whitehouse is shrewd” – but he has to admit that even he couldn’t take the respectable face that the Gay Pride Rally attempted to put on homosexuality. “The reason I sang ‘Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay’ at the rally in Hyde Park was because I found out who the speakers were – like the “Gay Vicar of Thaxted’ (a safe, religious homosexual frontman); Ian Harvey (former Tory MP) . . . there was nobody radical there at all.” So Robinson performed ‘SIYGTB’, followed by a song written by Bradford GLF (more of whom later). “Halfway through singing it a message came through from the police: ‘If he doesn’t shut up we’ll arrest him’. I had to stop in mid-song. Mind you, “Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay’ isn’t the most pro-police song.” I can imagine then being irritated . . . “Yes. We were surrounded and practically outnumbered. They used the same tactics on us as they later used on the blacks at Notting Hill, only the blacks wouldn’t put up with it. We did. We arrived at Hyde Park, and I think there were eleven buses of reinforcements waiting. And they made a little avenue for us to walk down into the park, and then just fanned out into a circle around us. A real heavy show of strength – like, ‘You may think you’re liberated, but just don’t come it!’”

The Notting Hill Carnival ’76, less than a month later . . . the rise of the National Front. “Coming to a realisation that gay people were copping it, was only a short way away from looking around and seeing that it’s happening every night in Brixton. You only have to open your eyes, once you realise it’s happening to you, to see it’s happening to other people. So yeah, that’s how I became politicised.” Three months later, infuriated with the lack of danger in Café Society, he quit the band and started fixing up gigs for a group that didn’t yet exist . . .

On its day, that group can be devastating. The Tom Robinson Band is one of the very best rock ‘n’ roll bands to emerge in the great rock renaissance. Without them, Tom would still be plugging away inside the closed world of sexual politics, instead of blasting out his ‘message’ in punk clubs and concert halls, in newspapers and on the radio. Without Danny Kustow, Brian Taylor and Mark Amber you would probably never have heard of Tom Robinson. What’s more, they’re all good interviewees, judging by what I’ve seen of them in print (particularly the excellent interview in Rock Against Racism’s ‘Temporary Hoarding No. 4’. However, the TRB feature awaits another writer. The idea of this one was sheer exploitation of the fact that Tom and I have been good mates for so long.

He is unique in that he is the only rock singer of the new breed of ‘street’ kids who actually had a solid ‘political’ involvement before he began singing about it. In fact, as the story shows, initially he sang for his bread and spent his spare time campaigning – totally the reverse of the singer who forms a band) or for that matter, the writer who loins a newspaper) and then finds an issue to beat his/her breast about. As Tom says, in a most telling turn of phrase, “You know, I’ve only been acclaimed as a campaigner for gay rights since I ceased to be one.” Although he hasn’t allowed his CHE membership to lapse, he is no longer involved in the nitty gritty of sexual politics. He doesn’t even do benefit gigs (preferring to donate gig money – like the recent Hope gig for Gay Switchboard) because the band find the audiences either too unresponsive or too preoccupied with the niceties of whether Tom demonstrates the correct stance. The classic example of that particular problem came with the celebrated incident in Bradford when the lesbians of the local Gay Liberation Front ‘zapped’ TRB – stormed on stage – during ‘Right On Sister’, accusing Tom of being patronising. Most people would come out of that incident cursing the women who interrupted the show. Tom’s reaction; “It’s cool. I stopped playing it at once. It was written as a statement of solidarity with those women, and if they don’t want it I’m just gonna play the next number.”

As it says on the sleeve of the new ‘Rising Free’ EP, on which ‘Right On Sister’ is the last track, the song was inspired by Jill Posener, a playwright whom Robinson worked with in Gay Sweatshop, because ‘That was the first time I’d worked with real dynamite lesbians. It’s not about women’s lot – that’s for women to write about. I wrote it from a man’s standpoint, and most women take it in the spirit it was intended. I can understand it if Spare Rib don’t like it when they review it – I dunno . . . But I’d just like to point out to women who find it patronising that I did have a letter from a 14 year old girl who said, ‘Dear Tom, thank you for ”Right On Sister”. I thought me and my pen friend in Norway were the only two who felt like that.’ Now that girl doesn’t care what’s right on or politically correct, but that one little song, stupid and banal as it is, touched a chord in her. I hope that means something to feminists. There’s such a danger with the Left generally –and people involved in sexual politics in particular – that the things they attack are on their own side. For instance, the Bradford GLF lesbians zap us but not the Stranglers. It’s their party trick. The rest of the band were totally freaked out by it,” he chuckles.

It’s evident that Tom actually quite relishes the ins and outs of the gay politics he reckons to have left behind. Nevertheless, its obvious he must now reach thousands of hung-up gay kids who’ve never even heard of CHE, GLF or Kinsey, and would never dare to read Gay News. His grounding in sexual politics is a breath of fresh air in rock music. For a supposedly libertarian genre, there are an astounding number of people in this business who don’t even realise how much their exploitation of their own and others’ conditioned responses to sex reinforce an oppressive status quo. Tom Robinson has sexual oppression sussed. Amazingly, he’s the first major rock singer to simply be homosexual rather than pose about and use the ‘abnormality’ of gayness as titillation. As Steve Clarke observed, his onstage persona is “low-key macho”. He has a horror/fear of appearing camp, because for him it’s not a flirtation, it’s a hard fact. No bisexual chic, and no gratuitous outrage (not onstage at least – though he did manage to outdo any attempts at outrage I’ve ever seen when we went for a meal together at Christmas, in a posh West End restaurant, and Tom merrily sported an extraordinary ‘obscene’ Seditionaries fist-fuck T-shirt for all and sundry to blink at).

Robinson’s awareness of political games also makes him extremely wary. So resolutely upfront is he about his desire to be successful, I doubt whether even my most cynical colleague could berate TRB for selling out.” I wanna be a star,” Tom insists. But, I offer, you are also very dedicated to personal communication. The newsletter, free badges . . . “Only because that makes you more successful as a rock star,” Tom deadpans. “Obviously, if an audience feels personally involved they’ll enjoy it more. You give away a free badge that cost three pee to make; they’ll wear it as a present from the band. That’s sound marketing. I don’t understand why other people don’t do it. Kids pay £1,50 to see you, £4.00 for an LP, 80p for a single, £2.00 for a T-shirt . . . If you can’t give them a little three-pee tuppenny ha’penny badge, what’s it all about? If you make people feel you care about them, that makes them care about you. That’s why we write back to all letters. If you don’t, word gets about. So you send them badges even if they forget the stamped addressed envelope, and Charlie out in South Glamorgan tells all his friends, “Jesus, I got a personal reply, and I didn’t even send a stamped addressed envelope!” That’s ten people’s worth of good vibes. It all makes good financial sense.” So all these people who write to you are just being used? “I didn’t say that. But it does make perfect commercial sense.”

Even so, the sight of the TRB office in full spate during a letter-answering session is completely unnerving. I dropped round one evening recently – no set-up or anything – and there was the whole band and a couple of friends sitting on the floor surrounded by mountains of mail, scribbling and typing personal notes to stuff in all these envelopes along with badges, stickers and newsletters. Baffled, I retreated to manager Steve O’Rourke’s empty office (yes, that is Pink Floyd manager Steve O’Rourke . . . Tom reckons he’s such a nice guy, he was almost hurt when I expressed suspicion; good business sense again, as O’Rourke has already exerted his weight by getting EMI to put out what amounts to half an album at single price with ‘Rising Free’) and only the exhausted Danny Kustow was tempted off the factory floor to share my indolence. “The thing is,” Tom stresses, “all those things are not against my personal interests. Again, he’s completely honest about making compromises for commercial success – for instance in choosing ‘Motorway’ as the first single.

At the same time he praises to the skies bands who he reckons haven’t compromised, like the Sex Pistols (he recounts an incident at the Music machine where Johnny Rotten accosted him and hissed “Don’t ever give in” and was promptly sick on the carpet) and the feminist band Jam Today, whose stance is so ‘pure’ that their drummer even resents men being in the audience. Jam Today, he says, don’t make any bread, but they act as a “signpost for the rest of us”. On the other hand, I suggest, Jam Today don’t reach as many people as you. Would you say it was necessary for bands like them to inspire groups like yours, who are more likely to effect change? “NOOOO!” he howls, “I’m not gonna say that! Bollocks. I’m not gonna go round blowing that trumpet. I was pissed off when Ray Coleman (in Melody Maker) invented the quote ‘Clash and Pistols equivocate, we don’t’. I never said that. I said that their stance was equivocal, but I didn’t say immediately afterwards “we don’t.”

In fact, he proceeds to detail how he’s actually “ripped bits off” from those two bands, and later goes into a whole long list of people he’s blatantly taken ideas and inspiration from: Hot Peaches, Frank Zappa (Zappa used to do a kind of Mothers News column in some papers, which inspired the TRB bulletins), Hereward Kaye, The Kinks, Dylan, Bobo Phoenix (whose onstage ferocity with Dead Fingers Talk made Tom discard Café Society’s “discreet performance”), Robert Godfrey (whose persistence in keeping The Enid afloat through numerous trials and tribulations was another inspiration), Andy Fraser (“the guvnor bass player”) . . . “I’m a magpie,” he says. “I’m not an original thinker. I’ve gotta admit the only new thing about TRB is the synthesis.”

And, I would venture, the honesty and the extremism. Extremism? Yeah, I know what you’re thinking – TRB are safe. And it’s true. In a world where the rock audience’s senses have become blunted by ever more ludicrous extremes of outrage, in a world of pop groups bidding desperately to outdo one another for grotesque appellations (Moors Murderers, “Pretty Paedophiles”, etc.), in a world where rock journalists pretend to be literally bored to the point of suicide (if only . . .) and search for ever more nonsensical insults just because last week’s idol didn’t toe some party line that he or she hadn’t the least idea existed. . . In this world, yes, TRB are ‘safe’. They’re polite, they’re friendly, they don’t provoke riots. I would even doubt, despite their outspokenness about, say, homosexuality or the National Front, whether they are in any more physical danger than you or I – except, that is, when Tom frequents gay pubs like the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, which was recently raided by over a dozen heavies in NF badges who stormed in and smashed glasses, furniture and the barman’s ribs and hospitalised one customer before fleeing in waiting taxis.

Listen, I’ll tell you what’s extreme about Tom Robinson: he is making a stand on behalf of people. There is no mistaking what he’s saying, no way – apart from the odd ode to a motorcar or some tiresome imaginary brother – that any TRB song, uh, equivocates. And he’s not just preaching to the converted (not that it would necessarily invalidate anything if he were) because not only is he going to reach an audience who came to rock first and listen later, but also his major statement – that human rights are inseparable, that you can’t divide it up into homosexuals, immigrants, women, etc, etc, that you have to decide which side you’re on – that statement is a cliché only for those who can’t be bothered to think about it. It is extreme. It requires that hoary old beast: constant re-evaluation of oneself. Our prejudices are so conditioned into us that even now – after watching and supporting the gay movement from the outside for several years – even now I listen to ‘Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay’ or Tom’s Jimmy Centola rap, and I discover that there is still room to lower my personal barrier of irrational fear of homosexuals by another notch. The work of twenty years is not necessarily undone in less than a decade.

Tom Robinson, I would suggest, is extreme because he is rational. Normally we think of people as extremists – Patti Smith or Johnny Rotten, for instance – for exactly the opposite reason; because they lay bare their irrationality. This sparks against our own insecurity, and our need to come to terms with their extremism is cathartic – and, incidentally, a powerful factor in their success, both artistic and commercial. But Tom Robinson is just plain old rational. Straight. Mr Nice Guy. In fact, I’m slightly surprised he’s so popular in these times of mental machismo . . . Characteristically, Tom tries hard to defuse any attempts to lumber him with a saintly image, and I don’t blame him. But everyone is someone else’s guru, and in some respects Tom Robinson is mine right now. It’s easy to become complacent about truisms like the evil of the National front, and Robinson’s constant reiteration of his beliefs acts upon me in the same way it would appear that, say, Jam Today inspire him.

Finally, let me make a guess about the album. See, they’ve already dispensed with most of the off-centre stuff; ‘Motorway’, ‘I Shall Be Released’ (the George Ince song), ‘Don’t Take No For An Answer’ (the Ray Davies song), ‘Martin’, ‘Glad To Be Gay’, ‘Right On Sister’. Which leaves . . . ‘Up Against The Wall’, ‘Power In The Darkness’, ‘Long Hot Summer’, ‘Winter Of ‘79’, ‘I’m All Right Jack’, ‘Better Decide Which Side You’re On’, ‘We Ain’t Gonna Take It’, . . . the street-fighting songs, the wide-screen anti-Front songs, the backlash songs. Take a listen to ‘Don’t Take No For An Answer’ on the new EP. LOUD. Now think; Chris Thomas is producing the album, that band is playing it, those are the songs they’re playing . . . I tell you, it will be a real fist in the face of oppression – our oppression as well as “theirs”. A clenched fist, naturally.

kperry

September 10, 2008 at 1:28 amgreat to hear these old TRB songs again Thanks for up’ing them. If I can find it I have a Cassette of TRB at the Bottom Line in New York City, was a radio broadcast. If I can find it I will post it to media fire and let ya all know of the link

cheers

betab

September 10, 2008 at 1:18 pmStill a superb first album.

Most of the post TRB stuff available on Tom’s own website for download

John Mullen

November 5, 2008 at 10:00 amI’m writing a history article about political rock. If anyone has articles or memories about Tom Robinson’s effects in the late seventies, I’d love to hear from them. In particular the attempts by the band to encourage political mobilization, and the difficulties of doing so as a rock star…Thanks

baron von zubb

November 5, 2008 at 6:19 pmUp against the wall…

Oh I get it now. It’s a quickshagsong.

What a naughty boy he was.

Jimmy Centola

November 20, 2008 at 7:33 pmVery nice writing and regards to Tom. While “Centola” was the name I used early in my erstwhile career, my name is actually Jimmy Camicia and I imagine the poem which turned on Tom was “Change For A Dying Queen,” which can be accessed all over the internet. Sincerely, Jimmy

Merrick

February 26, 2009 at 10:10 pmI’ve often wondered what would’ve happened if Up Against The Wall had been TRB’s first single. It’s got such a killer punch to it and great social observation lyrics, it would’ve scorched a blazing trail.

2468 Motorway might’ve had more populist appeal, but that was precisely why it didn’t gel with the burgeoning punk/new wave scene.

Merrick

April 8, 2010 at 4:47 pmThanks for reprinting this massive and fascinating article.

I’ve just done an entire site for Glad To Be Gay, with the background and the various versions Tom’s done over the years. The Links page has a link to your crucial page.