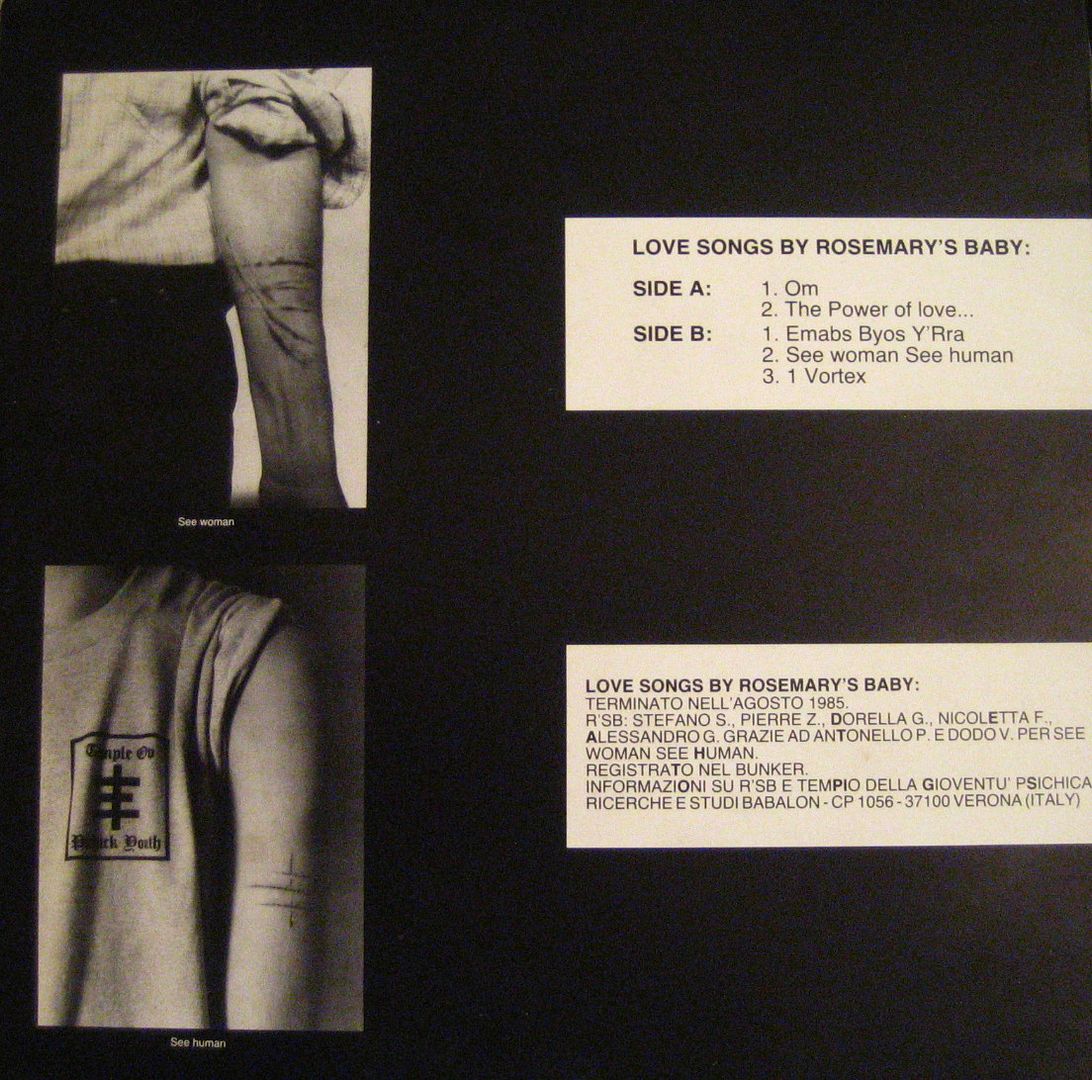

Emabs Byos Y’Rra / See Woman See Human / 1 Vortex

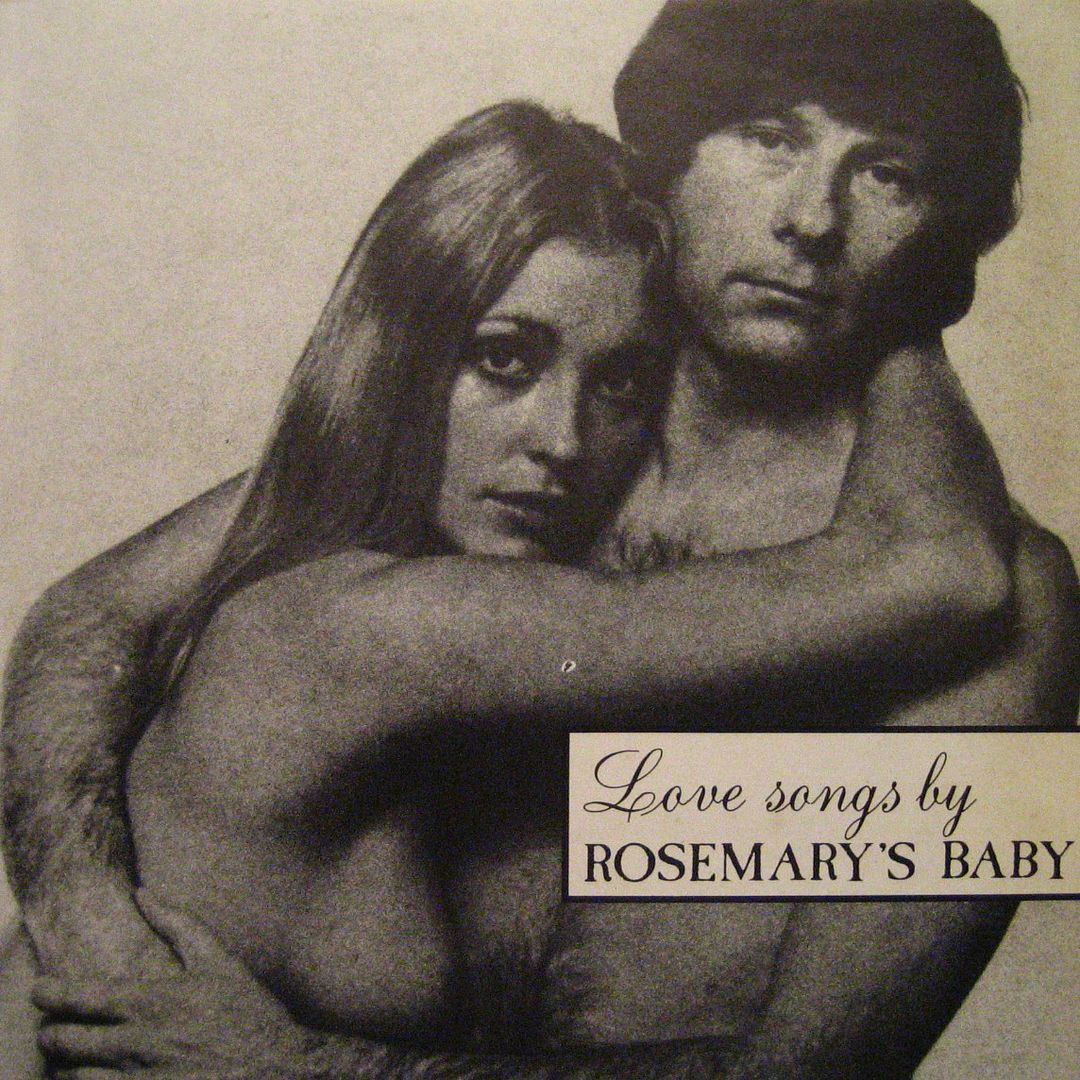

Rosemary’s Baby was the musical arm of Ricerche Studi Babalon (RSB), the Italian ‘access point’ of the Temple Ov Psychick Youth (T.O.P.Y.), which issued tapes, booklets, bulletins and videos.

Rosemary’s Baby’s main man was Pierre Luigi Zoccatelli. His ideas were rooted in Aleister Crowley’s Thelema and Magick, later turning into Guenonian Christianism.

For Rosmemary’s Baby’s first performance, Zoccatelli plastered the streets of Verona with posters, drawn up in the typical style of Italian funeral notices, simply announcing that “Rosemary’s Baby is born”. Unfortunately the local media thought that these posters announced the creation of a new group of Satanists in Verona. From that point on, the Verona public decided that Zoccatelli was a practising Satanist…

Since the short lived Rosemary’s Baby days, Zoccatelli decided to wander down the rather dubious route of the Alleanza Cattolica / Alleanza Nazionale. K.Y.P.P do not endorse, or share the views of this fundamentalist far right Catholic organisation.

This very rare 12″ record got me a verbal ticking off from Genesis P’Orridge when one day he heard the record being played upstairs on the sound system at his home in Hackney.

No trouble with the 12″ record as T.O.P.Y. were distributing it, or me for using his sound system.

The problem was that his young daughter Caresse was in the room at the time. Genesis quite rightly in hindsight, did not appreciate Caresse hearing this 12″ record.

This is a 12″ record to summon demons with.

Halloween history and traditions

Halloween, celebrated each year on October 31, is a mix of ancient Celtic practices, Catholic and Roman religious rituals and European folk traditions that blended together over time to create the holiday we know today. Straddling the line between fall and winter, plenty and paucity and life and death, Halloween is a time of celebration and superstition. Halloween has long been thought of as a day when the dead can return to the earth, and ancient Celts would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off these roaming ghosts. The Celtic holiday of Samhain, the Catholic Hallowmas period of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day and the Roman festival of Feralia all influenced the modern holiday of Halloween. In the 19th century, Halloween began to lose its religious connotation, becoming a more secular community-based children’s holiday. Although the superstitions and beliefs surrounding Halloween may have evolved over the years, as the days grow shorter and the nights get colder, people can still look forward to parades, costumes and sweet treats to usher in the winter season.

Halloween’s origins date back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain.

The Celts, who lived 2,000 years ago in the area that is now Ireland, the United Kingdom, and northern France, celebrated their new year on November 1. This day marked the end of summer and the harvest and the beginning of the dark, cold winter, a time of year that was often associated with human death. Celts believed that on the night before the new year, the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead became blurred. On the night of October 31, they celebrated Samhain, when it was believed that the ghosts of the dead returned to earth. In addition to causing trouble and damaging crops, Celts thought that the presence of the otherworldly spirits made it easier for the Druids, or Celtic priests, to make predictions about the future. For a people entirely dependent on the volatile natural world, these prophecies were an important source of comfort and direction during the long, dark winter.

To commemorate the event, Druids built huge sacred bonfires, where the people gathered to burn crops and animals as sacrifices to the Celtic deities.

During the celebration, the Celts wore costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins, and attempted to tell each other’s fortunes. When the celebration was over, they re-lit their hearth fires, which they had extinguished earlier that evening, from the sacred bonfire to help protect them during the coming winter.

By A.D. 43, Romans had conquered the majority of Celtic territory. In the course of the four hundred years that they ruled the Celtic lands, two festivals of Roman origin were combined with the traditional Celtic celebration of Samhain.

The first was Feralia, a day in late October when the Romans traditionally commemorated the passing of the dead. The second was a day to honor Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees. The symbol of Pomona is the apple and the incorporation of this celebration into Samhain probably explains the tradition of “bobbing” for apples that is practiced today on Halloween.

By the 800s, the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands. In the seventh century, Pope Boniface IV designated November 1 All Saints’ Day, a time to honor saints and martyrs. It is widely believed today that the pope was attempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related, but church-sanctioned holiday. The celebration was also called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmesse meaning All Saints’ Day) and the night before it, the night of Samhain, began to be called All-hallows Eve and, eventually, Halloween. Even later, in A.D. 1000, the church would make November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to honor the dead. It was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades, and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels, and devils. Together, the three celebrations, the eve of All Saints’, All Saints’, and All Souls’, were called Hallowmas.

Halloween has always been a holiday filled with mystery, magic and superstition. It began as a Celtic end-of-summer festival during which people felt especially close to deceased relatives and friends. For these friendly spirits, they set places at the dinner table, left treats on doorsteps and along the side of the road and lit candles to help loved ones find their way back to the spirit world.

Today’s Halloween ghosts are often depicted as more fearsome and malevolent, and our customs and superstitions are scarier too. We avoid crossing paths with black cats, afraid that they might bring us bad luck. This idea has its roots in the Middle Ages, when many people believed that witches avoided detection by turning themselves into cats. We try not to walk under ladders for the same reason. This superstition may have come from the ancient Egyptians, who believed that triangles were sacred; it also may have something to do with the fact that walking under a leaning ladder tends to be fairly unsafe. And around Halloween, especially, we try to avoid breaking mirrors, stepping on cracks in the road or spilling salt.

But what about the Halloween traditions and beliefs that today’s trick-or-treaters have forgotten all about? Many of these obsolete rituals focused on the future instead of the past and the living instead of the dead. In particular, many had to do with helping young women identify their future husbands and reassuring them that they would someday, with luck, by next Halloween, be married.

In 18th-century Ireland, a matchmaking cook might bury a ring in her mashed potatoes on Halloween night, hoping to bring true love to the diner who found it. In Scotland, fortune-tellers recommended that an eligible young woman name a hazelnut for each of her suitors and then toss the nuts into the fireplace. The nut that burned to ashes rather than popping or exploding, the story went, represented the girl’s future husband. (In some versions of this legend, confusingly, the opposite was true: The nut that burned away symbolized a love that would not last.) Another tale had it that if a young woman ate a sugary concoction made out of walnuts, hazelnuts and nutmeg before bed on Halloween night, she would dream about her future husband. Young women tossed apple-peels over their shoulders, hoping that the peels would fall on the floor in the shape of their future husbands’ initials; tried to learn about their futures by peering at egg yolks floating in a bowl of water; and stood in front of mirrors in darkened rooms, holding candles and looking over their shoulders for their husbands’ faces.

Other rituals were more competitive. At some Halloween parties, the first guest to find a burr on a chestnut-hunt would be the first to marry; at others, the first successful apple-bobber would be the first down the aisle.

Another day with connections to Halloween is Guy Fawkes Day, celebrated on November 5. Guy Fawkes was a Roman Catholic who planned to blow up the Protestant House of Parliament on November 5, 1606; luckily for the House, he was apprehended and executed. Afterwards, the anniversary of the day was celebrated by building straw effigies, entreating passersby for “a penny for the Guy”, and finally burning “the Guys” in bonfires.

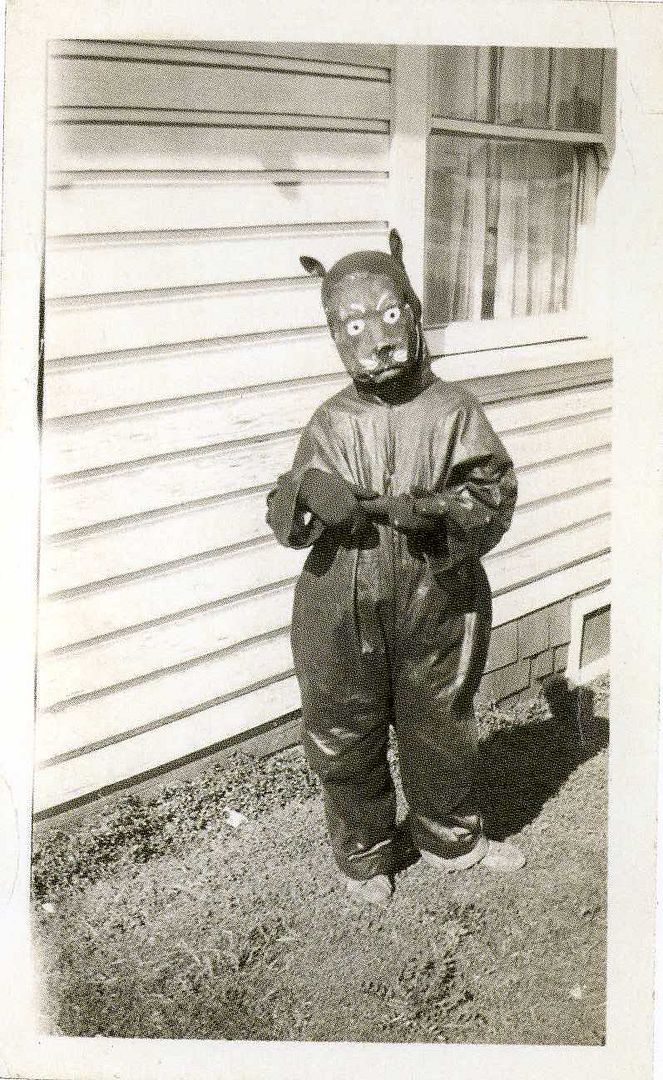

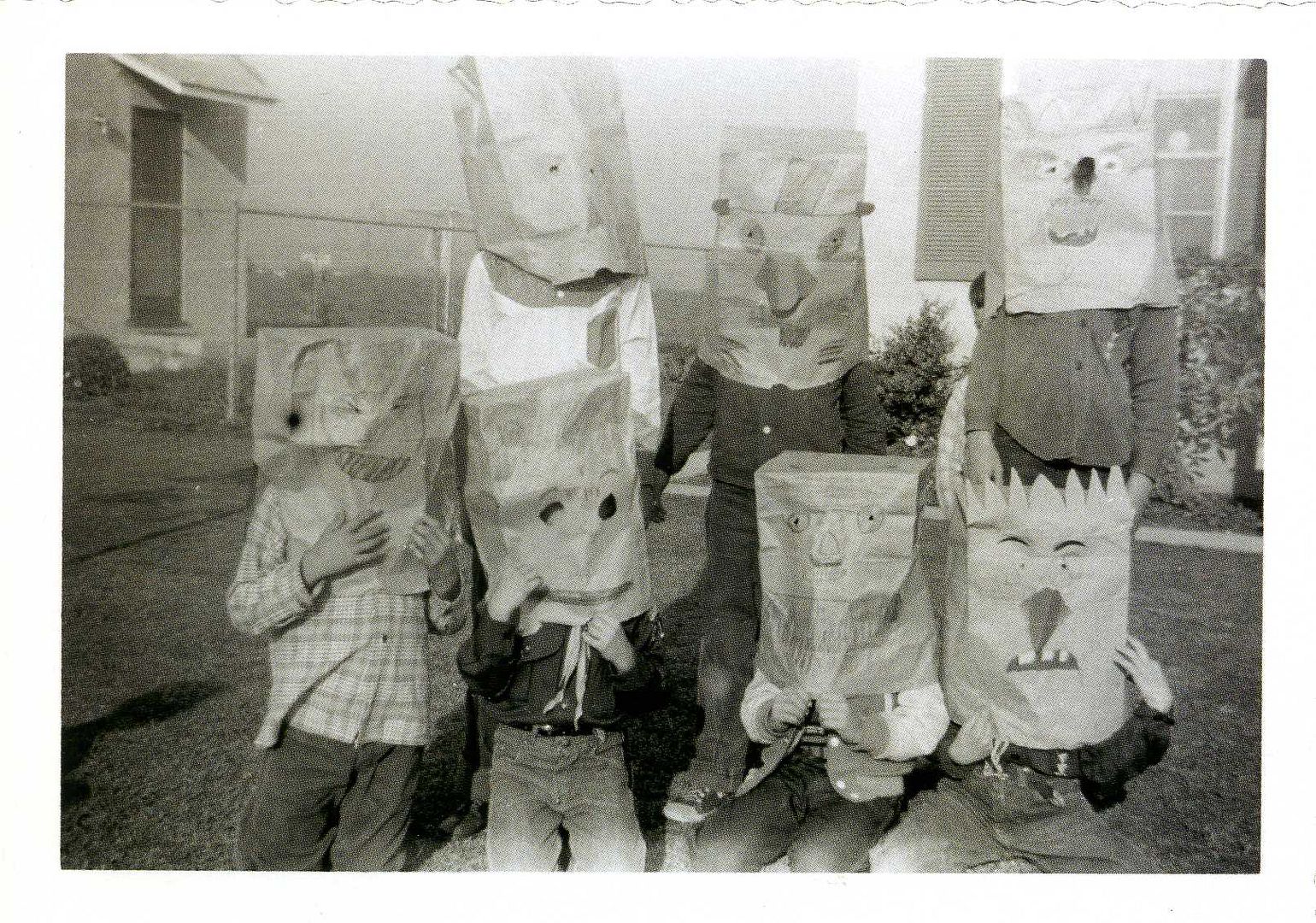

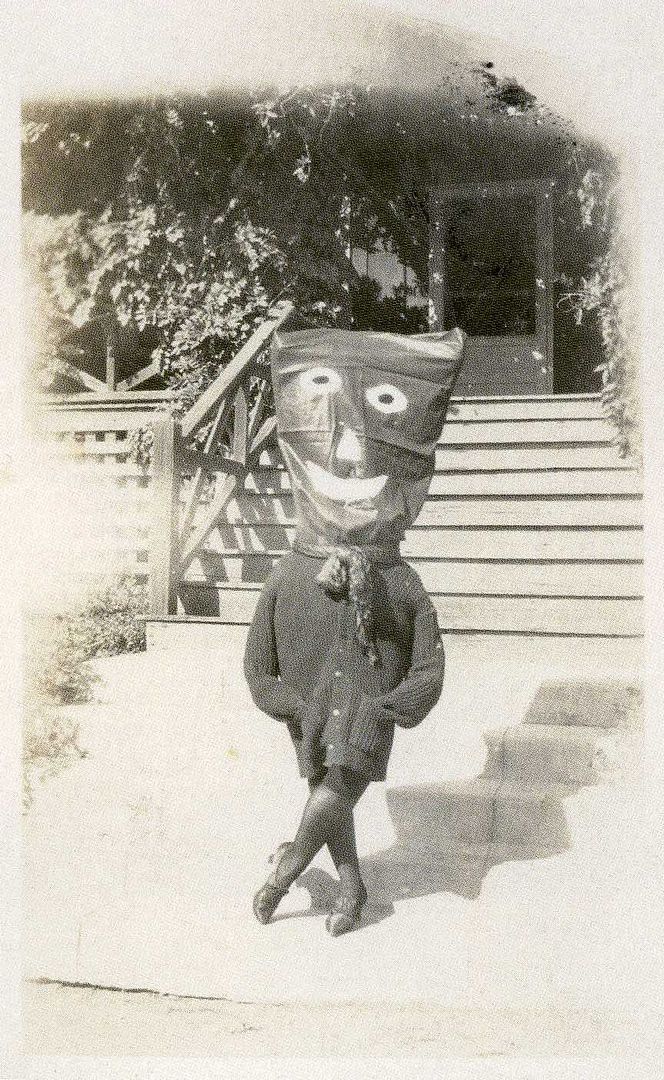

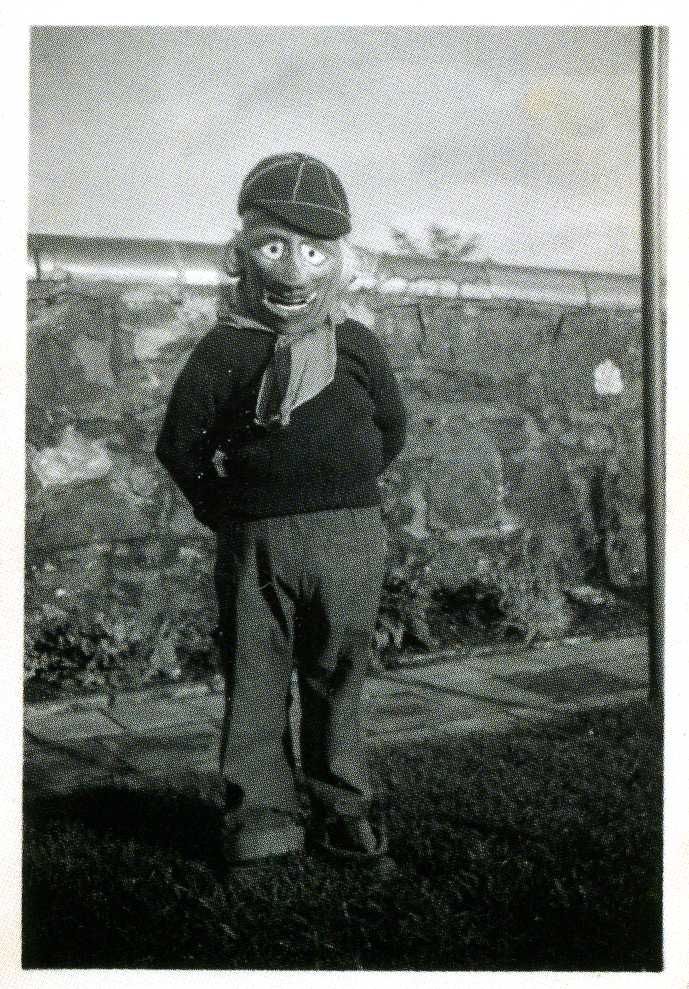

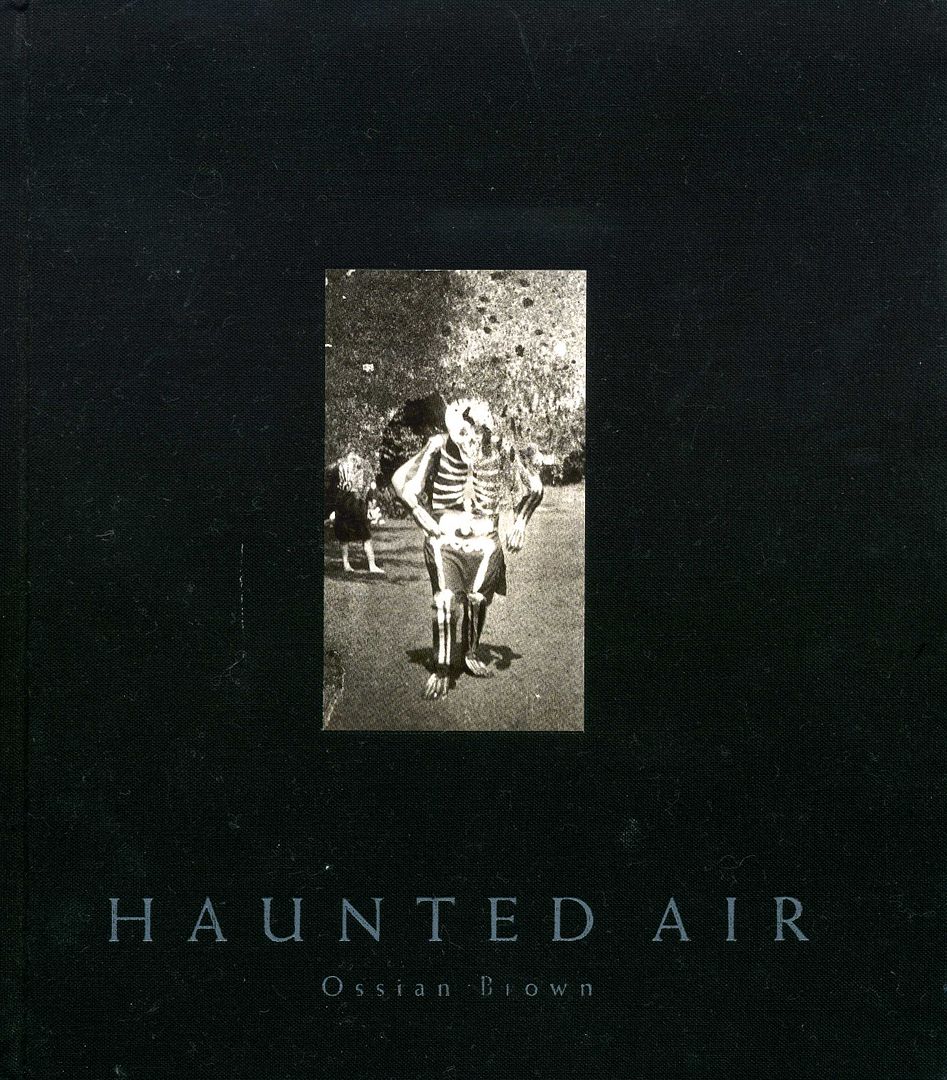

All the period photographs of Halloween children and adults that are displayed on this post are courtesy of the Ossian Brown book ‘Haunted Air’. Ossian has collated dozens of astonishing photographs for this charming and luxurious felt covered hardback book.

All the photographs were taken in the United States Of America between the late 19th and the mid 20th century.

I would like to thank Ossian for sending me two signed copies of this beautiful book, one which went straight up to Sheffield towards the eager hands of my younger brother who knew Ossian, as I did also, in the mid 1980s.

Ossian is a member of Cyclobe as well as working in collaboration with David Tibet’s Current 93.

Haunted Air is available now ISBN 9780224089708 published by Jonathan Cape with a forward passage by David Lynch and Geoff Cox.