Midsummers Day

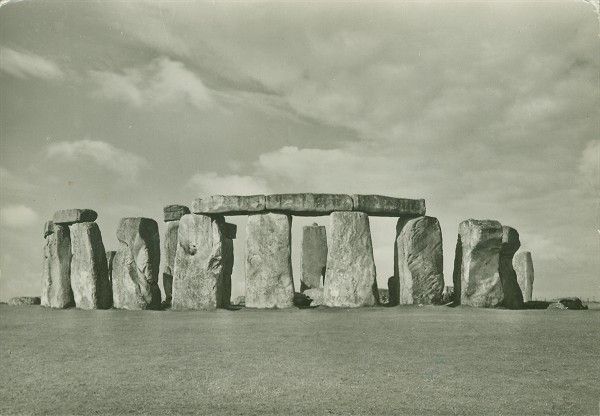

The festival is primarily a Celtic fire festival, representing the middle of summer, and the shortening of the days on their gradual march to winter. Midsummer is traditionally celebrated on either the 23rd or 24th of June, although the longest day actually falls on the 21st of June. The importance of the day to our ancestors can be traced back many thousands of years, and many stone circles and other ancient monuments are aligned to the sunrise on Midsummer’s Day. Probably the most famous alignment is that at Stonehenge, where the sun rises over the heel stone, framed by the giant trilithons on Midsummer morning.

In antiquity midsummer fires were lit in high places all over the countryside, and in some areas of Scotland Midsummer fires were still being lit well into the 18th century. This was especially true in rural areas, where the weight of reformation thinking had not been thoroughly assimilated. It was a time when the domestic beasts of the land were blessed with fire, generally by walking them around the fire in a sun-wise direction. It was also customary for people to jump high through the fires, folklore suggesting that the height reached by the most athletic jumper, would be the height of that years harvest.

After Christianity became adopted in Britain, the festival became known as St John’s day and was still celebrated as an important day in the church calendar; the birthday of St John the Baptist. Traditionally St John’s Eve (like the eve of many festivals) was seen as a time when the veil between this world and the next was thin, and when powerful forces were abroad. Vigils were often held during the night and it was said that if you spent a night at a sacred site during Midsummer Eve, you would gain the powers of a bard, on the down side you could also end up utterly mad, dead, or be spirited away by the fairies.

Indeed St Johns Eve was a time when fairies were thought to be abroad and at their most powerful (hence Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream).

St John’s Wort was also traditionally gathered on this day, thought to be imbued with the power of the sun. Other special flowers (Vervain, trefoil, rue and roses) were also thought to be most potent at this time, and were traditionally placed under a pillow in the hope of important dreams, especially dreams about future lovers.

The festival is still important to pagans today, including the modern day druids who (barring any trouble) celebrate the solstice at Stonehenge in Wiltshire. For them the light of the sun on Midsummer’s Day signifies the sacred Awen. For witches the summer solstice forms one of the lesser sabbats, their main festivals being Beltane (1st May) and Samhain. Some occultists still celebrate the ancient festivals around 11 days later than our calendar; this marks the 11 days, which were lost when the Gregorian calendar replaced the Julian calendar in 1751.

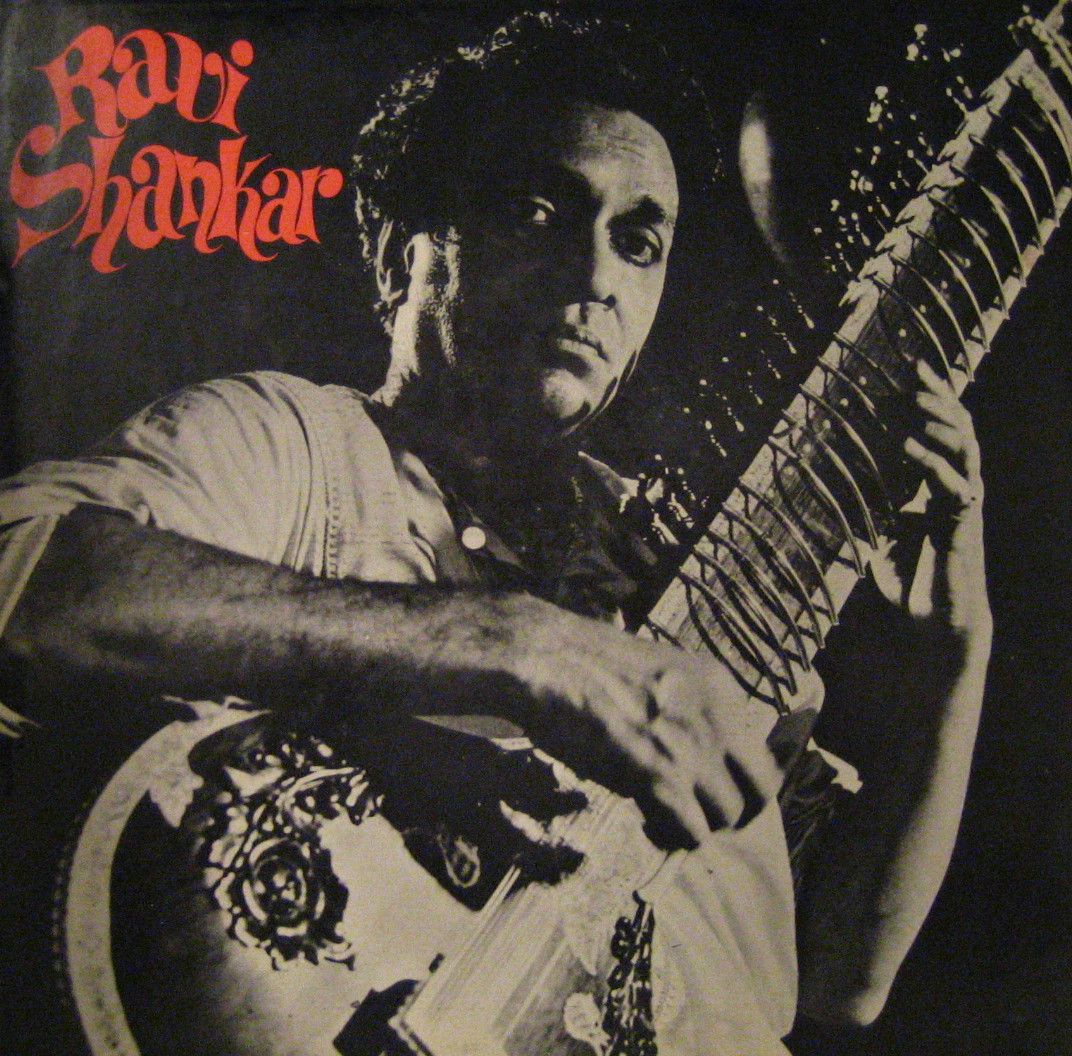

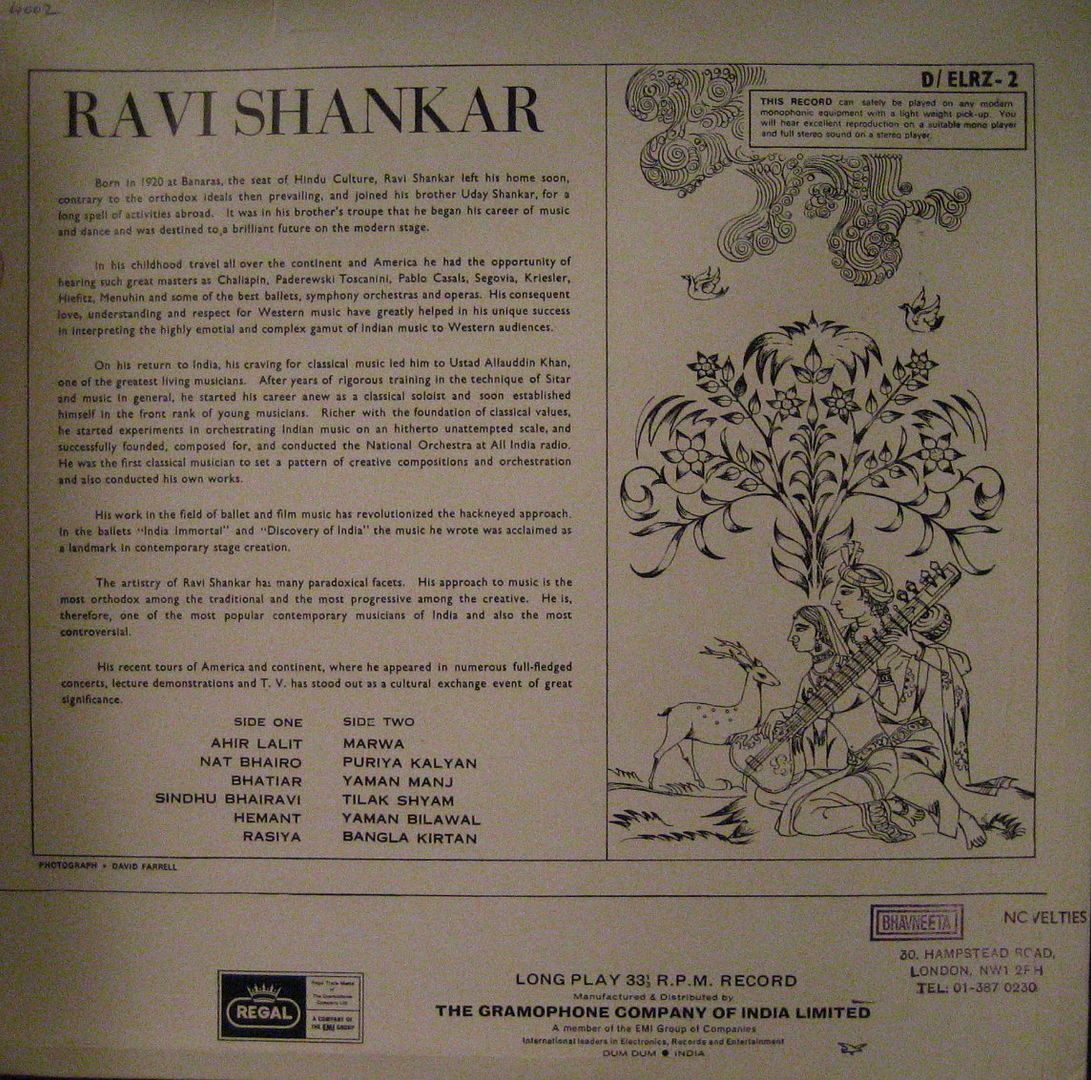

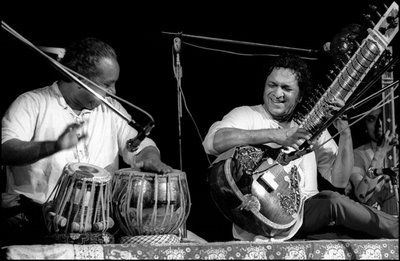

Ravi Shankar – Regal Records – 1969

Ahir Lalit / Nat Bhairo / Bhatiar / Sindu Bhairavi / Hemant / Rasiya

Marwa / Puriya Kalyan / Yaman Manj / Tilak Shyam / Yaman Bilawal / Bangla Kirtan

Pandit Ravi Shankar (Bengali: রবি শংকর, “Pandit” is honorific) (born April 7, 1920) is a Bengali Indian sitar player and composer. He is a disciple of Baba Allauddin Khan, the founder of the Maihar gharana of Hindustani classical music, and the father of Grammy-award-winning singer-songwriter Norah Jones and sitar player Anoushka Shankar.

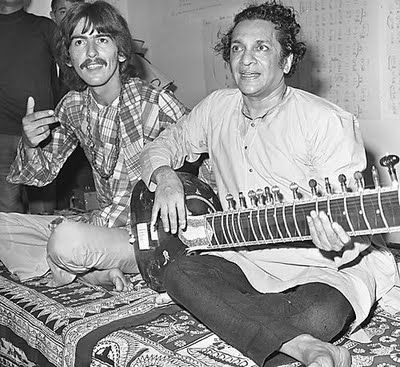

Ravi Shankar is a leading Indian instrumentalist of the modern era. He has been a longtime musical collaborator of tabla-players Ustad Allah Rakha, Kishan Maharaj and intermittently also of sarod-player Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. His collaborations with violinist Yehudi Menuhin, film maker Satyajit Ray, and The Beatles (in particular, George Harrison) added to his international reputation.

He has received many awards throughout his career, including three Grammy Awards and an Academy Award nomination. In 1999, Ravi Shankar was awarded the Bharat Ratna award, India’s highest civilian honor.

Ravi Shankar was born in Benares, India. His family originally hails from Narail, Jessore district, East Bengal, now in Bangladesh.

His first wife, sitarist Annapurna Devi is the daughter of his teacher, Ustad Alauddin Khan. They had a son, Shubhendra Shankar (1942-92), who was also a musician.

Shankar later had two other children, singer Norah Jones in 1979 with Sue Jones and sitarist Anoushka Shankar in 1981 with Sukanya Shankar. Shankar is also the brother of dancer and choreographer, Uday Shankar, with whom he started giving stage shows as a child artist. He is the uncle of Indian musician Ananda Shankar and of the Indian dancer and actress Mamata Shankar. It is worth noting that despite popular belief, the Tamil violinist L. Shankar is not related to Ravi.

Ravi Shankar has been on stage from the age of 10 and has been all over the world as a dancer and a musician. He first performed publicly in India in 1939. He finished his formal training in 1944 and worked out of Mumbai (Bombay). He began writing scores for film and ballet and started a recording career with HMV’s Indian affiliate Regal Records. He became music director of All India Radio in the 1950s. From 1946 onwards he began to compose original music for films. Some of his most noted scores include the ones for Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy and Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. He also composed the tune for Saare Jahan Se Achcha.

Ravi Shankar then became well known to the music world outside India, first performing in the former Soviet Union in 1954 and then the West in 1956. He performed in major events such as the Monterey Pop Festival and at major venues such as the Royal Festival Hall.

Already performing in major concert halls all around the world, Shankar, having attained pop cultural fame, was invited to play venues that were unusual for a classical musician, such as the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival in Monterey, California, with Ustad Allah Rakha on tabla.

He was also one of the artists who performed at the Woodstock Festival in 1969, and with George Harrison was one of the organizers of The Concert for Bangladesh in 1971, in an attempt to raise awareness of the growing crisis (see 1970 Bhola cyclone, Bangladesh Liberation War and 1971 Bangladesh atrocities carried out by West Pakistan Army) that was occurring in East Pakistan (now independent Bangladesh) at the hand of West Pakistan Army where Shankar’s family origins lay. It was Ravi Shankar who asked George Harrison for his help to raise funds for Bangladesh. Ravi Shankar & Friends co-headlined Harrison’s 1974 tour of North America with mixed reviews. His final working album with Harrison was on a 1997 album, Chants of India, where Harrison developed an interest in chant music. After his colleague’s death on 29 November in 2001, following a long fight against cancer, Shankar, his daughter, Anoushka, along with Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Jeff Lynne, Eric Clapton, Tom Petty, Billy Preston, among many others attended the Concert for George in London, where Shankar dedicated the memorial to Harrison.

Shankar has been critical of some facets of the Western reception of Indian music. On a trip to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district after performing in Monterey, Shankar wrote,

“I felt offended and shocked to see India being regarded so superficially and its great culture being exploited. Yoga, Tantra, mantra, kundalini, ganja, hashish, Kama Sutra? They all became part of a cocktail that everyone seemed to be lapping up! ”

In 1969 he published an English language autobiography, “My Music, My Life”.

Always ahead of his time, Shankar has written two concertos for sitar and orchestra. His 3rd concerto will be given its debut performance by Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and his daughter Anoushka Shankar.The piece is scored for solo sitar and orchestra consisting of piccolo, oboe, English horn, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, timpani, 2 percussionists, harp and strings. In the first two concertos, Shankar doubled as composer and soloist. For his third concerto, commissioned by Orpheus, he calls on his daughter Anoushka Shankar, a leading sitar player of her generation and a rising world music star. To meet the challenge of notating Indian musical concepts in Western notation, Shankar enlisted the Welsh conductor David Murphy to help transcribe the work into an orchestral score. The concerto begins with an energetic orchestral overture, introducing the exotic musical language of sinuous melodies, shifting rhythms and drone notes. Unlike typical Western concert music, which derives much of its momentum from harmony and key relationships, Indian music builds intensity through melodic and rhythmic elaboration. Call-and-response passages offer special insight into the translation of the sitar’s sonorities into an orchestral idiom.

He has also written violin-sitar compositions for Yehudi Menuhin and himself, music for flute virtuoso Jean-Pierre Rampal, music for Hōzan Yamamoto, master of the shakuhachi (Japanese flute), and koto virtuoso Musumi Miyashita. He has composed extensively for films and ballets in India, Canada, Europe, and the United States, including Chappaqua, Charly, Gandhi (for which he was nominated for an Academy Award), and the Apu Trilogy. His recording Tana Mana, released on the Private Music label in 1987, penetrated the New Age genre with its unique combination of traditional instruments with electronics. In 2002, Ravi composed a piece for “The Concert for George.” He did not play at the concert, but his daughter Anoushka led an ensemble of Indian musicians in the piece. The classical composer Philip Glass acknowledges Shankar as a major influence, and the two collaborated to produce Passages, a recording of compositions in which each reworks themes composed by the other. Shankar also composed the sitar part in Glass’s 2004 composition Orion. Ravi Shankar has homes in Encinitas, California and New Delhi, Delhi, India.

Some of his well-known students are Kartik Kumar, Chandrakant Sardeshmukh, Guru Pitka, Deepak Chowdhury, Harihar Rao, Amiya Das Gupta, Shamim Ahmed, Partho Sarathy, Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, Manju Mehta, Shubhendra Rao, Kartik Seshadri, Stephen Slavek, Stephen James, Tarun Bhattacharya, Jaya Bose, and David Murphy. His daughter Anoushka started learning from him at the age of 8 and frequently accompanies him in concerts in addition to her solo performances.

Shankar is an honorary member of the International Rostrum of Composers. He has received many awards and honors from his own country and from all over the world, including 14 honorary doctorates, the Padma Vibhushan, Desikottam, the Magsaysay Award from Manila, three Grammy Awards, the Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize (Grand Prize) from Japan, and the Crystal Award from Davos, with the title “Global Ambassador”, to name but some. In 1986 he was nominated to be a member of the Rajya Sabha, India’s upper house of Parliament, for six years. In 2002, he was conferred the inaugural Indian Chamber of Commerce Lifetime Achievement Award. The Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honor, was awarded to him in 1999. In 1998 he was awarded the Polar Music Prize with Ray Charles. He shared an Academy Award nomination with George Fenton for Best Original Score to Gandhi (1982).

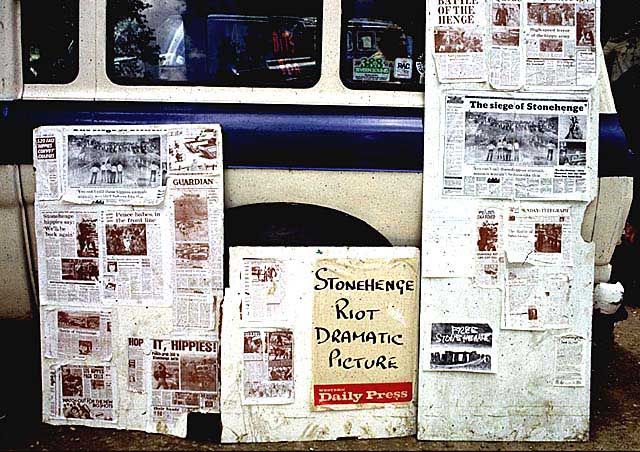

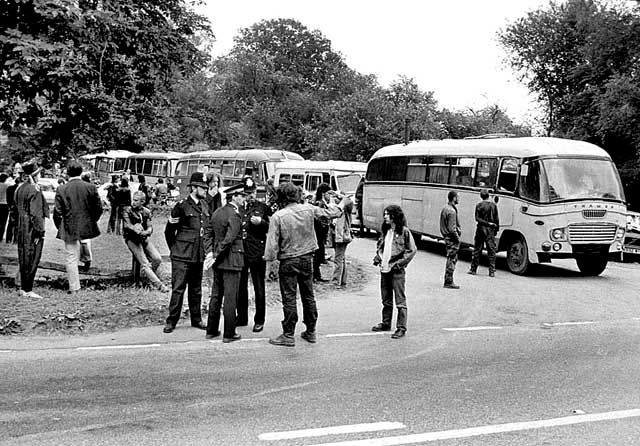

Anniversary of Stonehenge and the `Battle of the Beanfield’ 1st June 1985

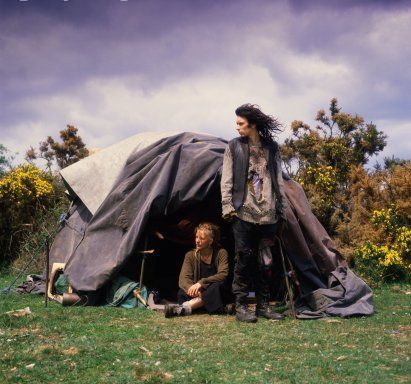

It’s 25 years this month, since the major trashing of my community, travelling on the way the make the “Peoples Free Festival of Albion” at Stonehenge. It was a regular event on the calender.

This is my account, of the events that day, and its aftermath …….

They said: something had to be done! Stonehenge appeared central to the situation. Police “Operation Solstice” was initiated.

At a meeting of the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), in early 1985, it was resolved to obtain a High Court Injunction preventing the annual gathering at Stonehenge. This was the device to be used to justify the attack at the “Battle of the Beanfield” on the 1st June in Hampshire. Well it wasn’t a battle really.

It was an ambush.

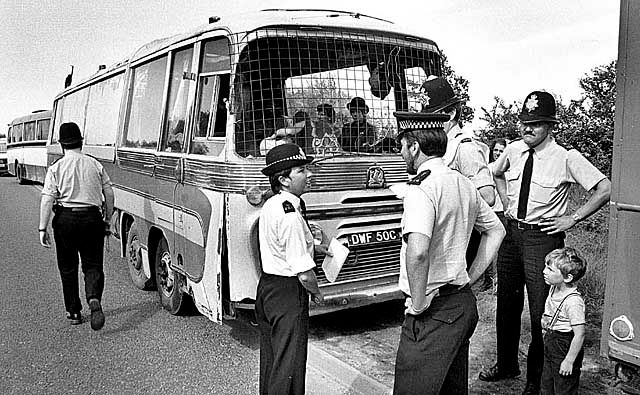

It was a magnificent convoy stretching and snaking its way over the Wiltshire Downs, as far as you could see in either direction. It was a warm Saturday afternoon as we drove through villages, people stood outside their garden gates, smiling and waving at us. A carnival atmosphere with little evidence of the ‘local opposition’ that we had been lead to believe was one of the reasons for obtaining the court orders.

A police helicopter watched overhead but there was little other sign of trouble until……..

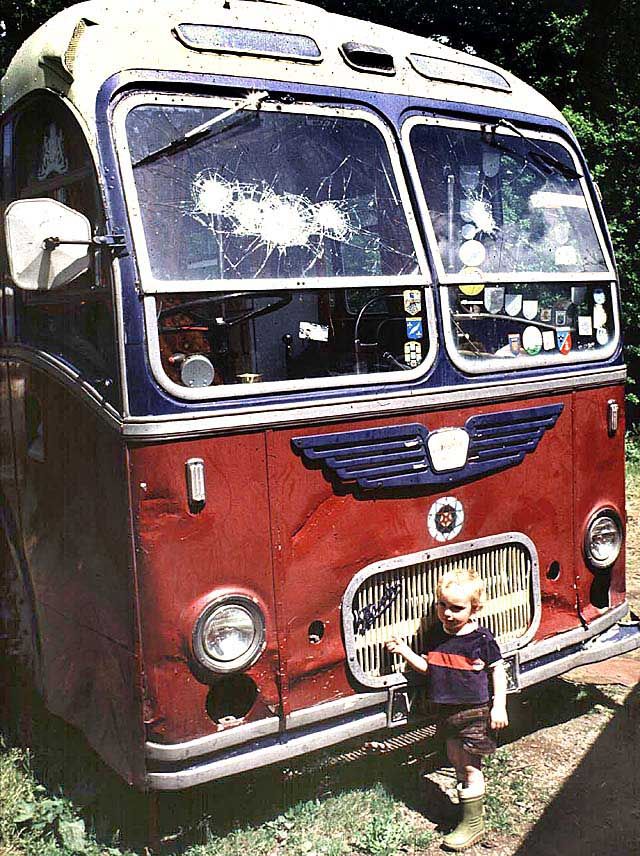

Seven miles from Stonehenge (the exclusion order was for four and a half miles), just short of the A303 and the Hampshire / Wiltshire border, two lorry loads of gravel where tipped across the road. Up to this point, no laws had been broken. I got out of my truck to take photographs when I first saw some twenty policemen running down the convoy ahead of me smashing windscreens without warning and ‘arresting’ / assaulting the occupants, dragging them out through the windscreens broken glass.

I and others who saw this were fearful of the level of violence used by the police in making arrests. Clearly we were in for a beating, again! Running back to our vehicles, we drove through a hedge in to the adjacent field.

The scale of the police operation was becoming obvious. The same level of violence had been applied to the rear of the convoy. Large numbers of police in many lines deep could be seen on the road forming up.

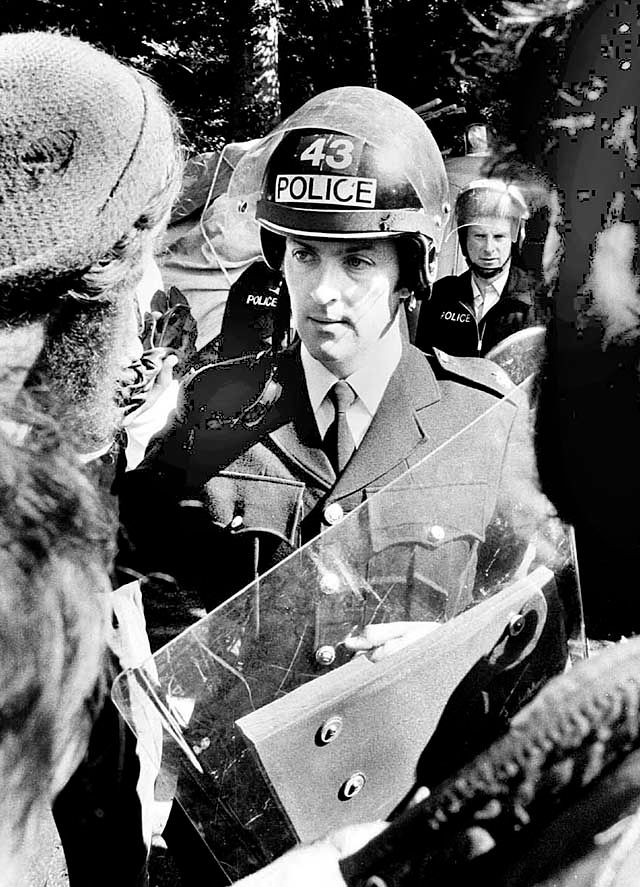

From then on, the situation grew more tense. More police reinforcements were brought up wearing one-piece blue overalls – without numbers!, ‘Nato-style’ helmets with visors and both full length perspex shields and circular black plastic shields. A ‘stand-off’ situation developed with sporadic outbreaks of violence.

Working with the festival welfare agencies, I was directed to a number of head injuries that has resulted from the initial conflict on the road. All of these injuries were truncheon wounds to the back of the head and some people were quite distressed. I was shown one man, about 20 years old who was semi-conscious with yet another head wound. I was fearful of him dying. An ambulance was called and I assisted the attendant and helped convey the casualty through police lines. The ambulance crew were initially apprehensive about their safety but assurances were given.

In between the taking of photographs, the copious first aid and concerns for my family and friends, I attempted to start negotiations and set up lines of communications with the middle-ranking ‘line’ officers. There was no ‘middle ground’ to be found, so, with others I organised a meeting with Assistant Chief Constable Lional Grundy. He was in charge of the overall operation. It was early evening before we were able to meet him. The tone of the meeting was ‘do what your told or else!’ He reiterated that people should be leave their vehicle and be arrested.

Because of the fear of what that might intail (after viewing the violence earlier in the day), those I met with were reticent about this. I met Grundy again a little later and attempted to reason further with him, but the ACC then threatened to arrest me for obstruction if I persisted.

Police in full kit were now massed in large numbers and obviously getting ready to charge. It turns out that police had been arresting a lot of people around Stonehenge earlier in the afternoon. At 7.00pm, Grundy had sixteen hundred policemen from six counties, Ministry of Defence police and some believe, army officers in police uniforms!!!

They had been briefed that we were all violent anarchists rather than a bunch of young people and families with children.

They charged.

The scenes that followed were recorded by media that had evaded the police blockade. The story was international news. ‘Dixon of Dock Green’ type policing was dead. That which Britain was noted for had now changed to para-military operations against minority groups.

Kim Sabido of ITN, a reporter used to visiting the worlds ‘hot spots’ did an emotional piece-to-camera as he described the worst police violence that he had ever seen.

“What we – the ITN camera crew and myself as a reporter – have seen in the last 30 minutes here in this field has been some of the most brutal police treatment of people that I’ve witnessed in my entire career as a journalist. The number of people who have been hit by policemen, who have been clubbed whilst holding babies in their arms in coaches around this field, is yet to be counted…There must surely be an enquiry after what has happened today”.

There wasn’t.

When the item was nationally broadcast on ITN news later that day, Sabido’s voice-over had been removed and replaced with a dispassionate narrator. The worst film footage was also edited out. When approached for the footage not shown on the news, ITN claimed it was missing. Sabido said.

“When I got back to ITN during the following week and I went to the library to look at all the rushes, most of what Id thought wed shot was no longer there,” recalls Sabido. “From what I’ve seen of what ITN has provided since, it just disappeared, particularly some of the nastier shots.”

Some but not all of the missing footage has since surfaced on bootleg tapes and was incorporated into the Operation Solstice documentary shown on Channel Four in 1991.

Public knowledge of the events of that day are still limited by the fact that only a small number of journalists were present in the Beanfield at the time. Most, including the BBC television crew, had obeyed the police directive to stay behind police lines at the bottom of the hill “for their own safety”.

One of the few journalists to ignore police advice and attend the scene was Nick Davies, Home Affairs correspondent for The Observer. He wrote:

“There was glass breaking, people screaming, black smoke towering out of burning caravans and everywhere there seemed to be people being bashed and flattened and pulled by the hair….men, women and children were led away, shivering, swearing, crying, bleeding, leaving their homes in pieces…..Over the years I had seen all kinds of horrible and frightening things and always managed to grin and write it. But as I left the Beanfield, for the first time, I felt sick enough to cry.”

During the charge, I took photographs, but I put my camera away. My (ex) -wife and I comforting and cuddles with each other for fear, before we were attacked..

530 were arrested that day (both at the Beanfield and at Stonehenge), the most in any operation since the Second World War.

Photographic evidence is scant because of the nature of the action. Ben Gibson, a freelance photographer working for The Observer that day, was arrested in the Beanfield after photographing riot police smashing their way into a Traveller’s coach. He was later acquitted of charges of obstruction although the intention behind his arrest had been served by removing him from the scene. Most of the negatives from the film he managed to shoot disappeared from The Observers archives during an office move.

A friend and fellow photographer Tim Malyon narrowly avoided the same fate:

“Whilst attempting to take pictures of one group of officers beating people with their truncheons, a policeman shouted out to get him and I was chased. I ran and was not arrested.”

Tim Malyon’s negatives have also been lost with only a few prints surviving.

One unusual eye-witness to the Beanfield nightmare was the Earl of Cardigan, secretary of the Marlborough Conservative Association and manager of Savernake Forest (on behalf of his father the Marquis of Ailesbury). He had travelled along with the convoy on his motorbike accompanied by fellow Conservative Association member John Moore. As the Travellers had left from land managed by Cardigan, the pair thought “it would be interesting to follow the events personally”. Wearing crash helmets to disguise their identity, they witnessed what Cardigan described to Squall as `unspeakable’ police violence.

Cardigan subsequently provided eye-witness testimonies of police behaviour during prosecutions brought against Wiltshire Police.

These included descriptions of a heavily pregnant woman “with a silhouette like a zeppelin” being “clubbed with a truncheon” and riot police showering a woman and child with glass. “I had just recently had a baby daughter myself so when I saw babies showered with glass by riot police smashing windows, I thought of my own baby lying in her cradle 25 miles away in Marlborough,” recalls Cardigan.

After the Beanfield, Wiltshire Police approached Lord Cardigan to gain his consent for an immediate eviction of the Travellers remaining on his Savernake Forest site.

“They said they wanted to go into the campsite `suitably equipped’ and `finish unfinished business’. Make of that phrase what you will, says Cardigan. “I said to them that if it was my permission they were after, they did not have it. I did not want a repeat of the grotesque events that I’d seen the day before.”

Instead, the site was evicted using court possession proceedings, allowing the Travellers a few days recuperative grace.

As a prominent local aristocrat and Tory, Cardigans testimony held unusual sway, presenting unforeseen difficulties for those seeking to cover up and re-interpret the events at the Beanfield.

In an effort to counter the impact of his testimony, several national newspapers began painting him as a `loony lord’, questioning his suitability as an eye-witness and drawing farcical conclusions from the fact that his great-great grandfather had led the charge of the light brigade. The Times editorial on June 3rd claimed that being “barking mad was probably hereditary.”

As a consequence, Lord Cardigan successfully sued The Times, The Telegraph, the Daily Mail, the Daily Express and the Daily Mirror for claiming that his allegations against the police were false and for suggesting that he was making a home for hippies. He received what he describes as “a pleasing cheque and a written apology” from all of them. His treatment by the press was ample indication of the united front held between the prevailing political intention and media backup, with Lord Cardigans eye-witness account as a serious spanner in the plotted works:

“On the face of it they had the ultimate establishment creature – land-owning, peer of the realm, card-carrying member of the Conservative Party – slagging off police and therefore by implication befriending those who they call the powers of darkness,” says Cardigan.

“I hadn’t realised that anybody that appeared to be supporting elements that stood against the establishment would be savaged by establishment newspapers. Now one thinks about it, nothing could be more natural. I hadn’t realised that I would be considered a class traitor; if I see a policeman truncheoning a woman I feel I’m entitled to say that it is not a good thing you should be doing. I went along, saw an episode in British history and reported what I saw.”

For three days (and nights), without adequate food, sleep and many to a cell, we filled police stations across the south of England. From Bristol, where I was taken, to Southampton and London. We were then charged with the serious offence of ‘Unlawful Assembly’. Most charges were eventually dropped after all of this.

Some had lost everything they had. Parents where frantic in locating their children that had been taken into care. Vehicles had been taken to a ‘pound’ some 25 miles away and people had to go through further humiliation in reclaiming what was left of their homes.

Twenty-four of us took out a civil action against the Chief Constable of Wiltshire for the wrongs that were done to us that day. Nearly six years later at the High Court in Winchester, we won most of our case and were each awarded damages against the police. The Guardian said “Need to preserve pubic order does not permit the police to ride roughshod over the rights of ordinary people”. After a four month hearing, (during which we were made to feel like we were on trial), on the last day, the Judge made an order on court costs that, as we were getting legal aid, meant we got nothing.

What’s new!

As Lord Gifford QC, our legal representative, put it:

“It left a very sour taste in the mouth.”

To some of those at the brunt end of the truncheon charge it left a devastating legacy.

Things have never been the same again since the Beanfield. Throughout the rest of the year whether in small groups or at events, travellers were continually harassed.

It had defiantly changed us in many different ways. There was one guy who I trusted my children with in the early 80s – he was a potter, amongst other things. A nicer chap you couldn’t wish to meet. After the Beanfield I wouldn’t let him anywhere near them. I saw him, a man of substance, at the end of all that nonsense wobbled to the point of illness and evil. It turned all of us and I’m sure that applies to the whole travelling community. There were plenty of people who had got something very positive together who came out of the Beanfield with a world view of `fuck everyone’.

The berserk nature of the police violence drew obvious comparisons with the coercive police tactics employed on the miners strike the year before. Many observers claimed the two events provided strong evidence that government directives were para-militarising police responses to crowd control. Indeed, the confidential Wiltshire Police Operation Solstice Report released to plaintiffs during the resulting Crown Court case, states: “Counsels opinion regarding the police tactics used in the miners strike to prevent a breach of the peace was considered relevant.”

The news section of Police Review, published seven days after the Beanfield, stated:

“The Police operation had been planned for several months and lessons in rapid deployment learned from the miners strike were implemented.”

The manufactured reasoning behind such heavy-handed tactics was best summed up in a laughable passage from the confidential police report on the Beanfield:

“There is known to be a hierarchy within the convoy; a small nucleus of leaders making the final decisions on all matters of importance relating to the convoys activities. A second group who are known as the lieutenants or warriors carry out the wishes of the convoy leader, intimidating other groups on site.”

If the coercive policing used during the miners strike was a violent introduction to Thatcher’s mal-intention towards union activity, the Battle of the Beanfield was a similarly severe introduction to a new era of intolerance of Travellers.

25 years later, some of us still suffer the consequences of this action.

Alan ‘Tash’ Lodge

Information gained from the following sites:

mysteriousbritain.co.uk for Midsummers Day

lifeofthebeatles.blogspot.com for Ravi Shankar

indymedia.org.uk for The Battle Of The Beanfield.

Nick Hydra

June 21, 2010 at 10:18 amDocumentary on the Battle of the Beanfield: ‘Operation Solstice’ here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M_8txDkqRTY&feature=related

Trunt

June 21, 2010 at 2:08 pmGreat write up, I wasn’t there in 85, but remember it well. Is the top photo the original that Wilf sketched for the Mob. Anymore photo’s like this. Many thanks.

dan i

June 22, 2010 at 12:05 amStories that need to be told. Thanks for always posting on Midsummer’s Day Penguin.

Nick Hydra

June 24, 2010 at 8:40 pmHmm, having looked at a few of the youtube sites that have footage from ‘Operation Solstice’ most of them are either incomplete or low quality.

So, I have decided to upload my VHS copy and the 1st part is here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdztgEB5SlI

I hope to get the rest sorted in the next week or so…

Penguin • Post Author •

June 24, 2010 at 11:27 pmThanks for the effort Nick, and Trunt yes that is the photo Wilf used for his rejected Mob ‘Crying Again’ 12″ artwork.

dan i

June 29, 2010 at 11:08 pmMy mum is moving house this week and i cleared the last of my random things that she still had. I found KYPP 6, the journey to Stonehenge. I hadnt read it in years and it was still moving. The tale of Southern Death Cult particularly.

I especially enjoyed re-reading the hope for the future from Josef at the end – one day all Mob songs will sound like this. Lord Spit was the lyric, good but not a patch on Marius Moves or Smoke From Cromwell’s Time still then to come.

So thank you for that.