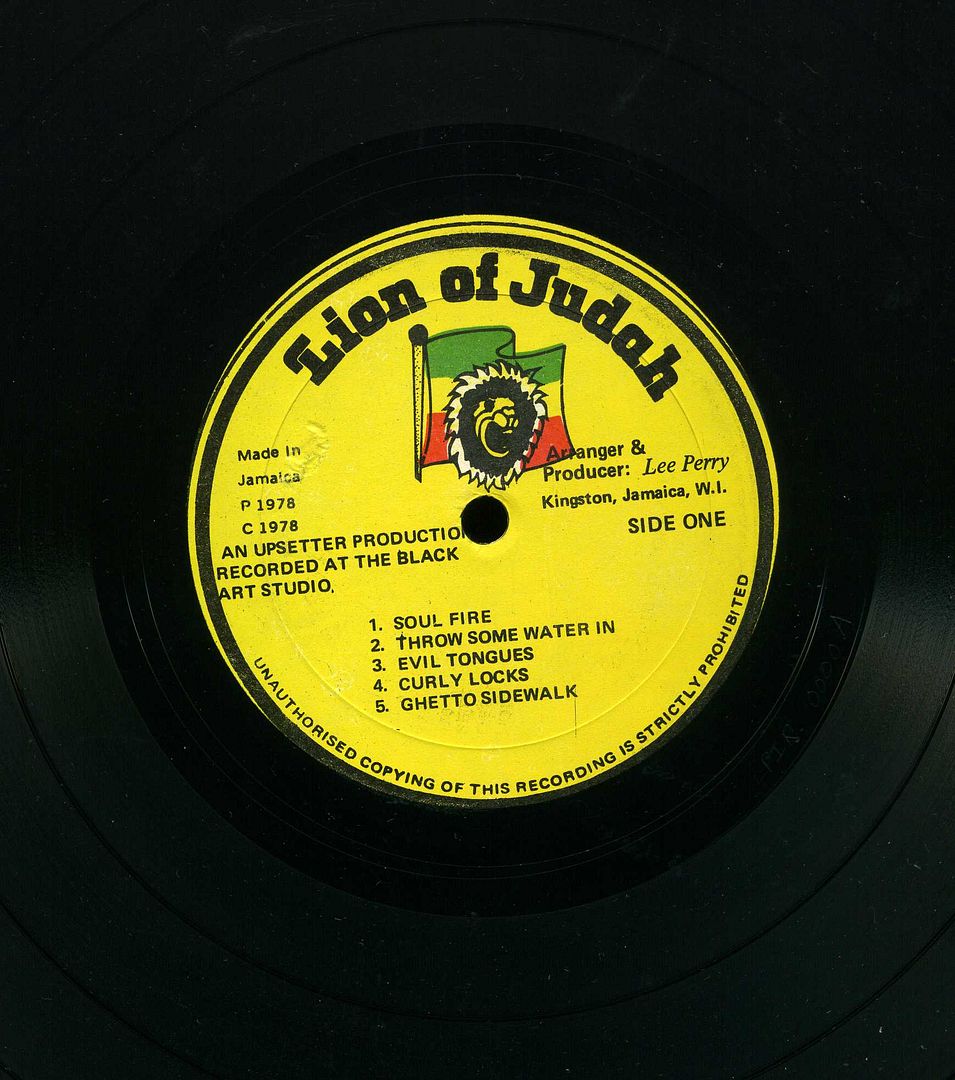

Soul Fire / Throw Some Water In / Evil Tongues / Curly Locks / Ghetto Sidewalk

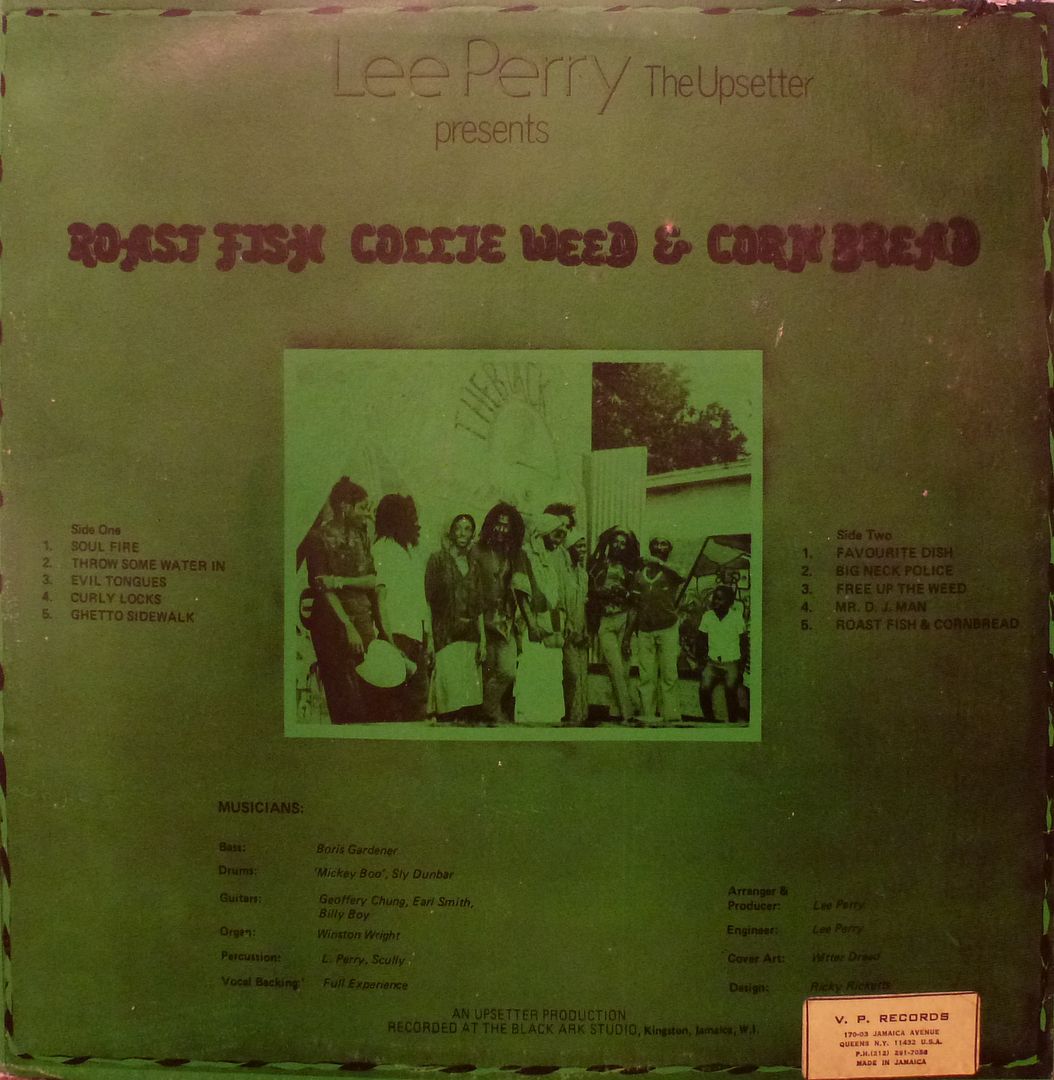

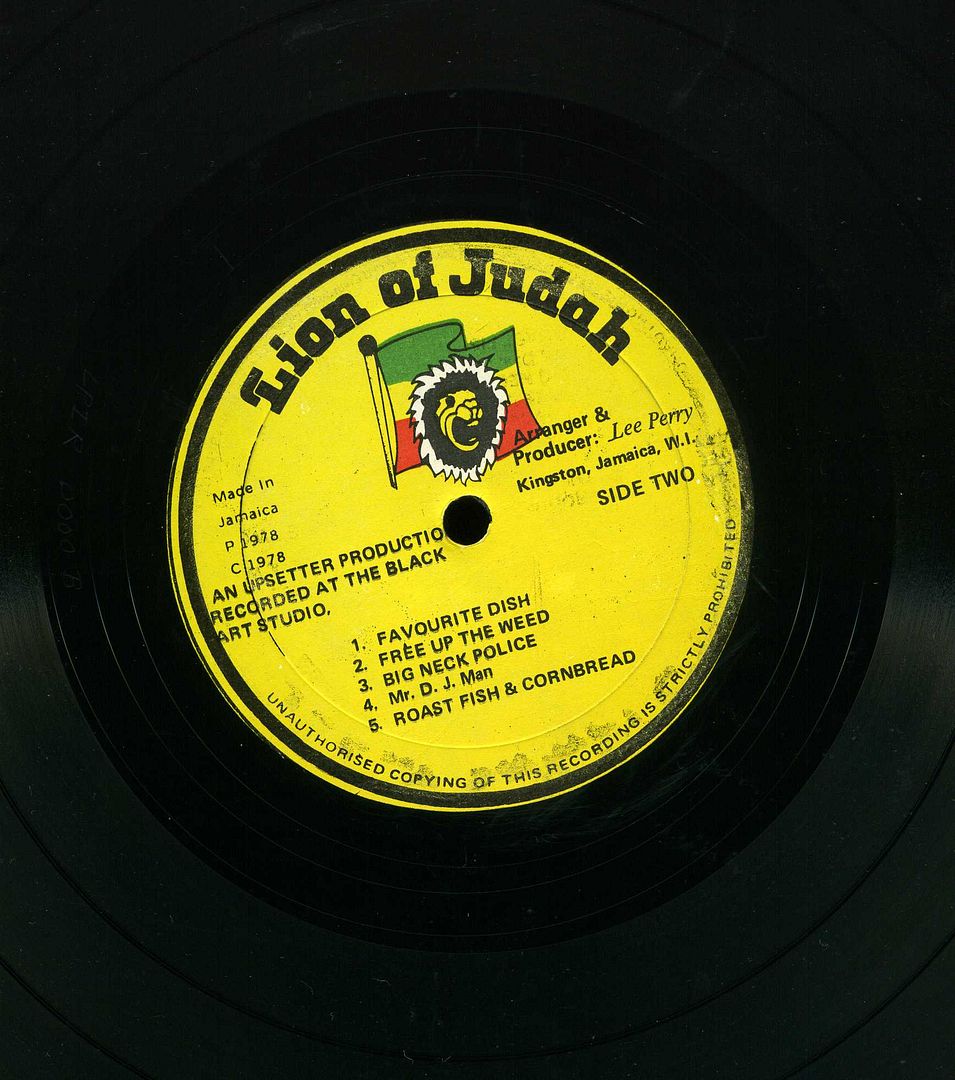

Favourite Dish / Free Up The Weed / Big Neck Police / Mr D.J Man / Roast Fish And Cornbread

Easing the KYPP browers into the new year with the first Lee Perry vocal album that was released in 1978 on Lee Perry’s own ‘Lion Of Judah’ imprint. This record is really rather good and gets a spin at least once a year right up here at the top of Penguin Towers, normally illegally loud and bass heavy!

I ripped off all the text from the All Music site, the New York based ‘Village Voice’ magazine and the rather ‘seasonal’ essay on the South Park Road Gun Court in Kingston, Jamaica was lifted from Da Wikki.

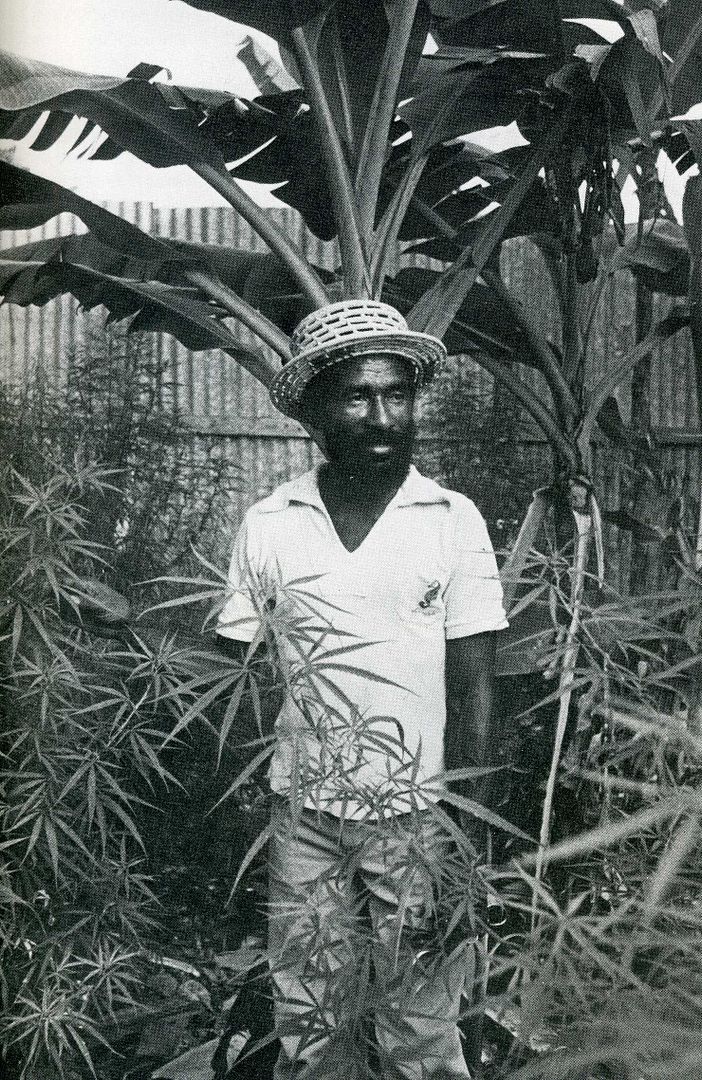

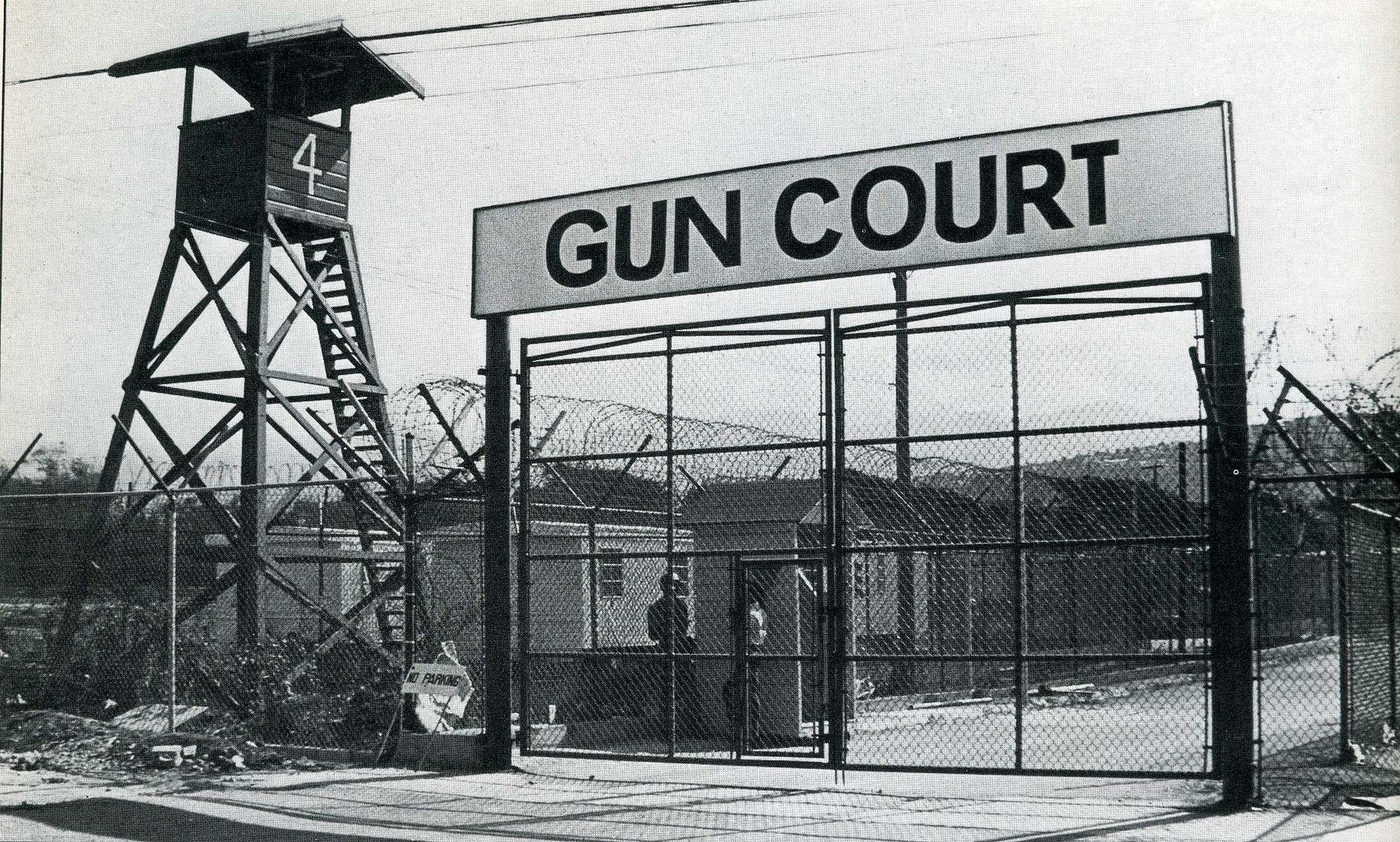

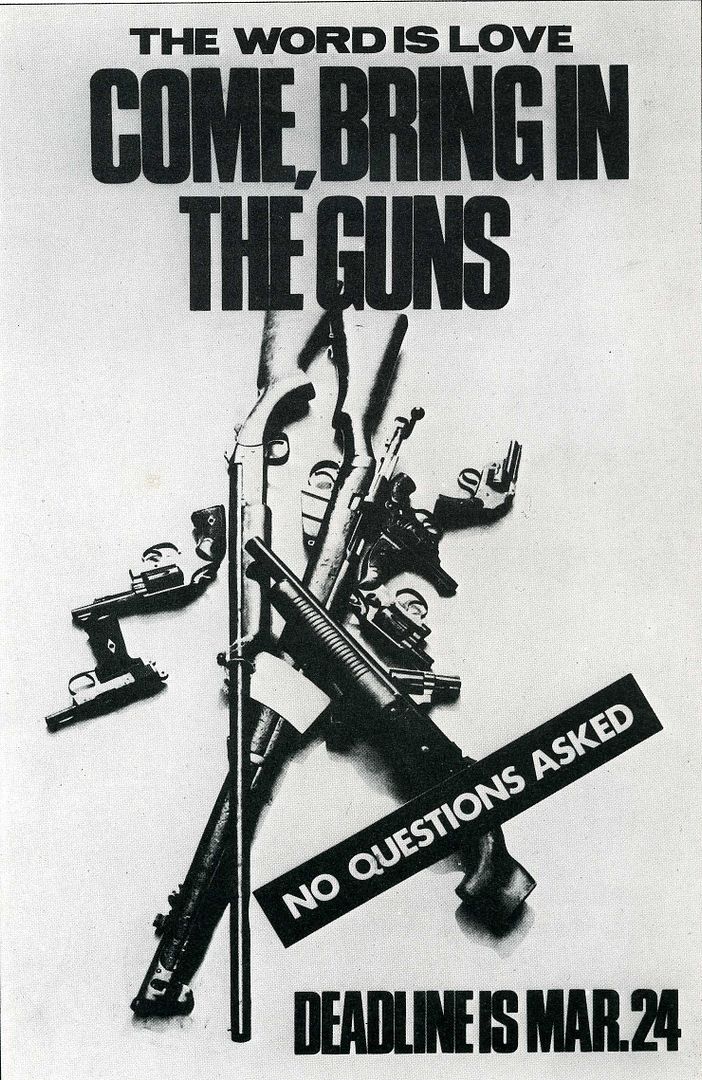

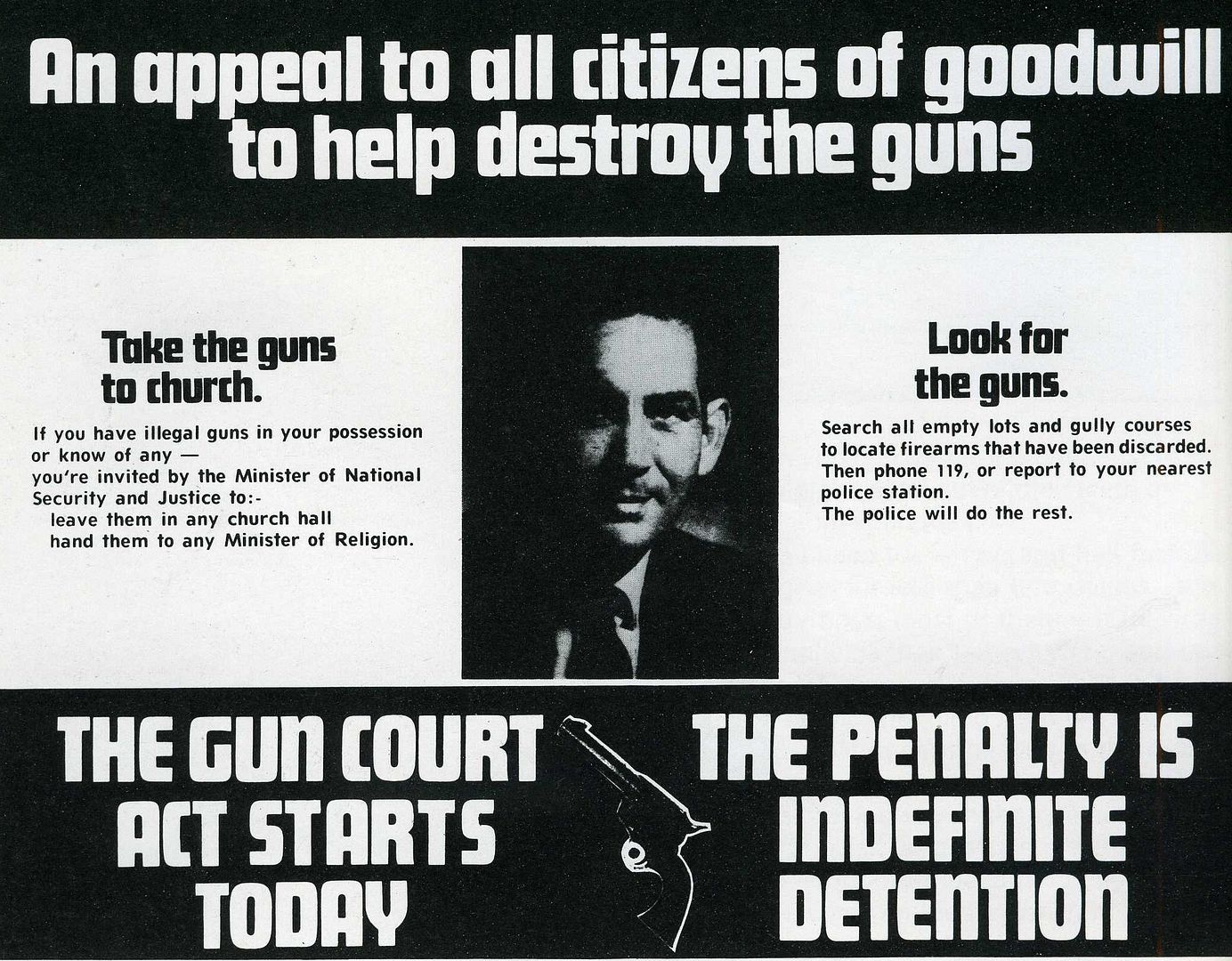

The photographs of Lee Perry and the Gun Court as well as the adverts for handing in your guns, were all scanned from one of the best books on the subject of reggae music and the general vibe of Jamaica, ‘Babylon On A Thin Wire’ which was published in 1976 and which has sadly been out of print for several decades now. A similar read to ‘Babylon On A Thin Wire’, and by the same writer, Michael Thomas and again with Adrian Boot photographs, is the book ‘Jah Revenge’ from 1978 which is also out of print as far as I know, and which also has been for decades. If you are interested in this subject then I would strongly recommend both these books assuming you can find them somewhere!

From us all here at KYPP online, we are all hoping that all the KYPP browsers worldwide will be safe, well, and have a pleasant and productive year ahead.

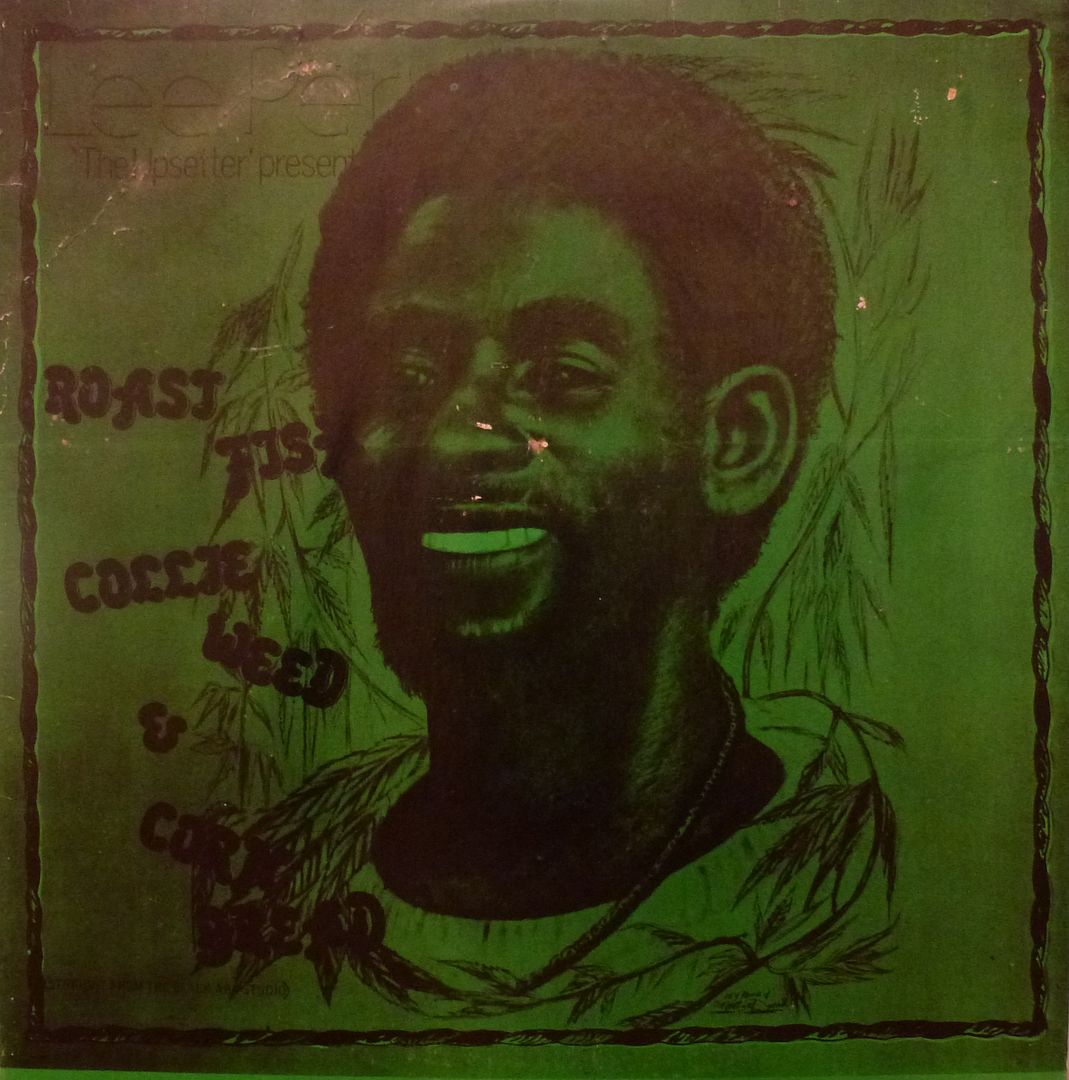

‘Roast Fish, Collie Weed And Cornbread’ was Lee Perry’s twentieth album, counting his sets, compilations, and full-length dub discs. Amazingly though, it was the first album Perry exclusively dedicated to his own vocal numbers. That, however, was not necessarily a strong selling point, as even his most devoted fans admit that Perry the singer is no equal to Perry the producer. And thankfully the set doesn’t open with his out of tune cover of Junior Byles’ sublime ‘Curly Locks’!

Knock out that track though, and you’re left with one of the most awe-inspiring albums of the decade, and even with that track, the album is still a masterpiece. It’s an extremely eclectic set, both thematically and musically, but without appearing flighty or unfocused.

There are wonderfully light-hearted moments, like the spectacularly dread title track, a song so heavy you expect Babylon to quake in the backing gladiator’s wake. But all the thick atmosphere, stalking rhythm, and ominous melody merely set the table for Perry to serve up and lavishly proclaim his favourite dish. Brilliant.

Equally entertaining is ‘Throw Some Water In’ as Perry equates proper auto maintenance to caring for one’s own body, a cheerful lesson on the importance of exercise and diet set to a vivacious reggae backing. It’s unclear if “Yu Squeeze My Panhandle” is meant to be humorous, although Perry’s pleading to the DJ to play his record is so over the top pitiful, one can’t imagine it’s anything but tongue in cheek, and all set to a slow, scorcher of a rhythm layered with percussion and weird effects.

A question mark also hovers around the intent of ‘Evil Tongues’ whose lyrics slip from condemning hypocrites down into the depths of paranoia. Unfortunately future events proved the lyrics all too prophetic in reflecting Perry’s slide into an emotional maelstrom. But so phenomenal is the claustrophobic production, it was still difficult to imagine that he was losing his way. In the cultural realm, ‘Big Neck Police’ revived Perry’s earlier single ‘Dreadlocks in Moonlight’ with additional percussion, searing sax solos, and female backing vocalists, creating a number that not only equalled the original, but bettered it. ‘Free Up the Weed’ was an impassioned, well-reasoned plea for legalization, while ‘Ghetto Sidewalk’ requested light for the sufferers.

The latter was a little overly ambitious musically, as Perry attempted to blend jazzy sax, studio effects and percussion, and a sturdy, tribal-tinged rhythm. Much more effective was ‘Soul Fire’ which layered instruments, effects, percussion, his own double-tracked vocals, and a mooing cow into a heady piece that defies categorization, but is laced with funk, soul, and the sound of classic Studio One.

And as highly experimental as many of the tracks are, the rhythms throughout are particularly inspired, with the productions equally intriguing, unlike many of Perry’s earlier excursions out to the musical fringe, these numbers are eminently entertaining and downright infectious, boasting strong melodies and, dare one say it, great vocals. This record was an extraordinary set.

JO-ANN GREENE – All Music

What makes Scratch so good is his distortion of the reggae mise-en-scene. In a basically conservative genre, producer Perry’s anti-science science of intuition and quick hands injects chance, humour, and disaster without ever really leaving the pop song behind.

Those who look to Perry’s shit talking for a cosmology will get burned; those who dismiss his output because of his shit talking will miss the aurora borealis of reggae.

‘Roast Fish Collie Weed & Corn Bread’ for example, one of the few records credited solely to Perry as artist and probably my favourite, pits house band rhythms against Perry’s pixie-dust percussion and mixing-desk abuse, over which Scratch narrates like a homeless Martha Stewart on how to stay healthy, how many lights are broken on his block etc. His microphone skills on any of his records are easily proto rap, his dub styling’s (like Jah Lion playing dominoes louder than Max Romeo’s singing on Norman ) are closer to John Cage than King Tubby.

‘Roast Fish Collie Weed & Corn Bread’ was all recorded at Black Ark with only a four-track 1/4-inch Teac reel-to-reel, 16-trackn Soundcraft board, Mutron phaser, and Roland Space Echo. Perry bouncing tracks together to create 16-track thickness, albeit with considerable signal degradation and tape hiss, Perry bubbled more than a Greenwich Village pavement in July and was guided by voices that could actually sing.

SASHA FRERE-JONES – Village Voice

In the early 1970s, Jamaica experienced a rise in violence associated with criminal gangs and political polarization between supporters of the People’s National Party and the Jamaica Labour Party. After a rash of killings of lawyers and businessmen in 1974, the government of Michael Manley attempted to restore order by granting broad new law enforcement powers in the Suppression of Crime Act and the Gun Court Act. The Suppression of Crime Act allowed the police and the military to work together in a novel way to disarm the people: soldiers sealed off entire neighbourhoods, and policemen systematically searched the houses inside for weapons without requiring a warrant. The goal was to expedite and improve enforcement of the 1967 Firearms Act, which imposed licensing requirements on ownership and possession of guns and ammunition, and prohibited automatic weapons entirely. Firearm licences in Jamaica require a background check, inspection and payment of a yearly fee, and can make legal gun ownership difficult for ordinary citizens. The new judicial procedures of the Gun Court Act were designed to ensure that firearms violations would be tried quickly and harshly punished.

Prime Minister Michael Manley expressed his determination to take stronger action against firearms, predicting that “It will be a long war. No country can win a war against crime overnight, but we shall win. By the time we have finished with them, Jamaican gunmen will be sorry they ever heard of a thing called a gun.” In order to win this war, Manley believed it necessary to fully disarm the public: “There is no place in this society for the gun, now or ever.”

The Gun Court Act and the Suppression of Crime Act were passed in special simultaneous sessions of the Senate and House of Representatives, and immediately signed into law by Governor-General Florizel Glasspole on April 1, 1974. The new court had several extraordinary features. Most trials were to be conducted in camera, without a jury and closed to the public and the press, in order to avoid problems of intimidation of witnesses and jurors. There was no provision for bail, either pre-trial or during appeal, since all defendants were considered dangerous. Most offences carried a single, mandatory sentence: indefinite imprisonment with hard labour. A convicted offender could be released only upon special decision of the Governor-General, advised by an appointed review board.

The unusual features of the Gun Court have faced legal challenges, some of which have forced amendment of the Gun Court Act. The case Hinds et al. v. the Queen was an early test case for the new court. Four men, Moses Hinds, Henry Martin, Elkanah Hutchinson, and Samuel Thomas, had been arrested and convicted by the Gun Court in 1974 for possession of firearms and ammunition without a licence. They appealed their sentences to Jamaica’s highest appellate court, the Court of Appeals, which initially declined to hear the case. However, they were allowed to apply to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, which agreed to review the legality of the Gun Court system.

The Constitution of Jamaica reserves certain serious crimes to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and its divisions. The Gun Court Act had established the Full Court division, with Resident Magistrates presiding, to try major firearms offences. The Privy Council held that this provision of the Act improperly encroached on the jurisdiction reserved for the Supreme Court, and that the Full Court division was therefore unconstitutional. This fault was remedied in 1976 by replacing the Full Court division with a new High Court division, presided over by a single Supreme Court justice. The Privy Council also found that the institution of an appointed review board to determine the length of sentences was contrary to the doctrine of separation of powers fundamental to the Westminster system of government. According to this principle, sentencing in each particular case is a function of the judiciary, and cannot be assigned to any other body. The 1976 amendment eliminated the review board entirely, leaving life imprisonment without review as the only possible sentence.

Another case, Trevor Stone v. the Queen, challenged the denial of jury trial for most gun offences. It was argued that trial by jury is a fundamental and constitutional right guaranteed by tradition in English common law. The Jamaican Court of Appeals rejected this argument in a decision written by Court President Ira DeCordova Rowe in 1980. The court noted that the written Constitution adopted by Jamaica upon independence guaranteed certain rights to criminal defendants, but omitted trial by jury. This case confirmed the Gun Court’s power to try all non-capital cases before judges alone.

The case of Herbert Bell v. Director of Public Prosecutions, concerning the right to a speedy trial, reached the Privy Council in 1983. The defendant had been held awaiting trial for several years, but the state ultimately failed to present any evidence or witnesses. When he was again arrested on the same firearms charges, he filed suit arguing that the Gun Court had violated his constitutional rights through unreasonable delay. The Privy Council agreed, ruling that even when prevailing local standards were taken into account, Bell’s trial had been excessively delayed through no fault of his own.

The Gun Court Amendment Act of 1983 allowed Resident Magistrates to grant pre-trial bail, and to decide whether to keep firearms cases in the Resident Magistrate’s Court or to send them to the High Court division of the Gun Court. Judges were given the power to set sentences other than life imprisonment. Cases involving defendants under 14 years old were directed to juvenile courts, instead of being heard by the ordinary Gun Court, and many young convicts serving indefinite sentences were released.

The Gun Court has faced criticism on several fronts, most notably for its departure from traditional practices, for its large backlog of cases, and for the continuing escalation in gun violence since its institution.

At the time of the 1976 amendments to the Act, the Jamaican Bar Association protested against the lack of jury trials and the harsh mandatory sentences. According to a report in the Virgin Islands Daily News, the Association’s Bar Council objected to the possibility that children as young as 12 could be imprisoned for life, without release or appeal, for small offences such as being found with used ammunition. The abrogation of jury trial has also been criticized by attorney and law professor David Rowe, the son of the Appeals Court justice who wrote the decision in the Stone case upholding the practice. Rowe argues that the common-law right to a jury trial is implied in the Constitutional provision for “a fair hearing within a reasonable time, by an independent and impartial court established by law,” concluding that the Constitution had been “shorn of its most potent and ancient safeguard, trial by jury.”