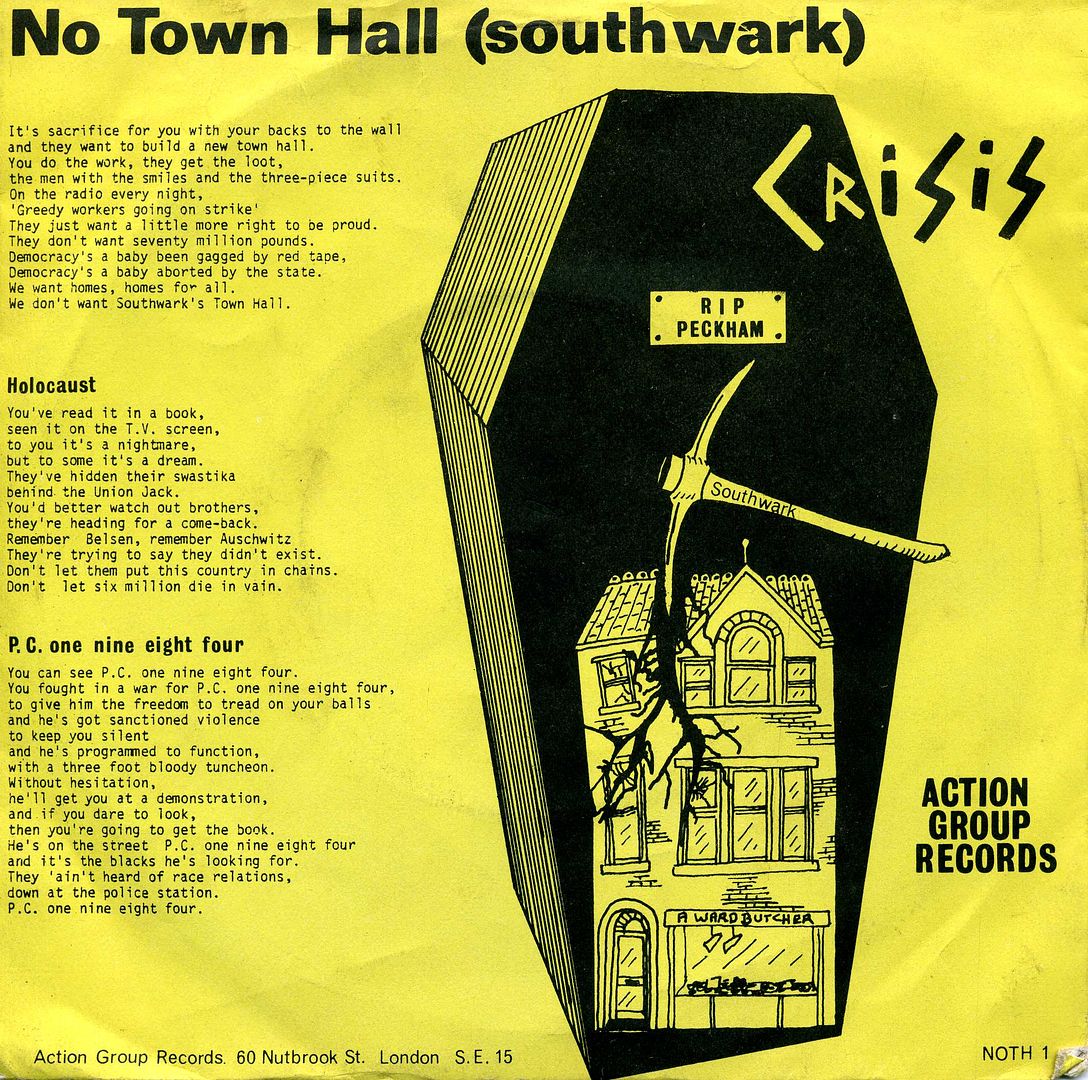

Holocaust / PC One Nine Eight Four

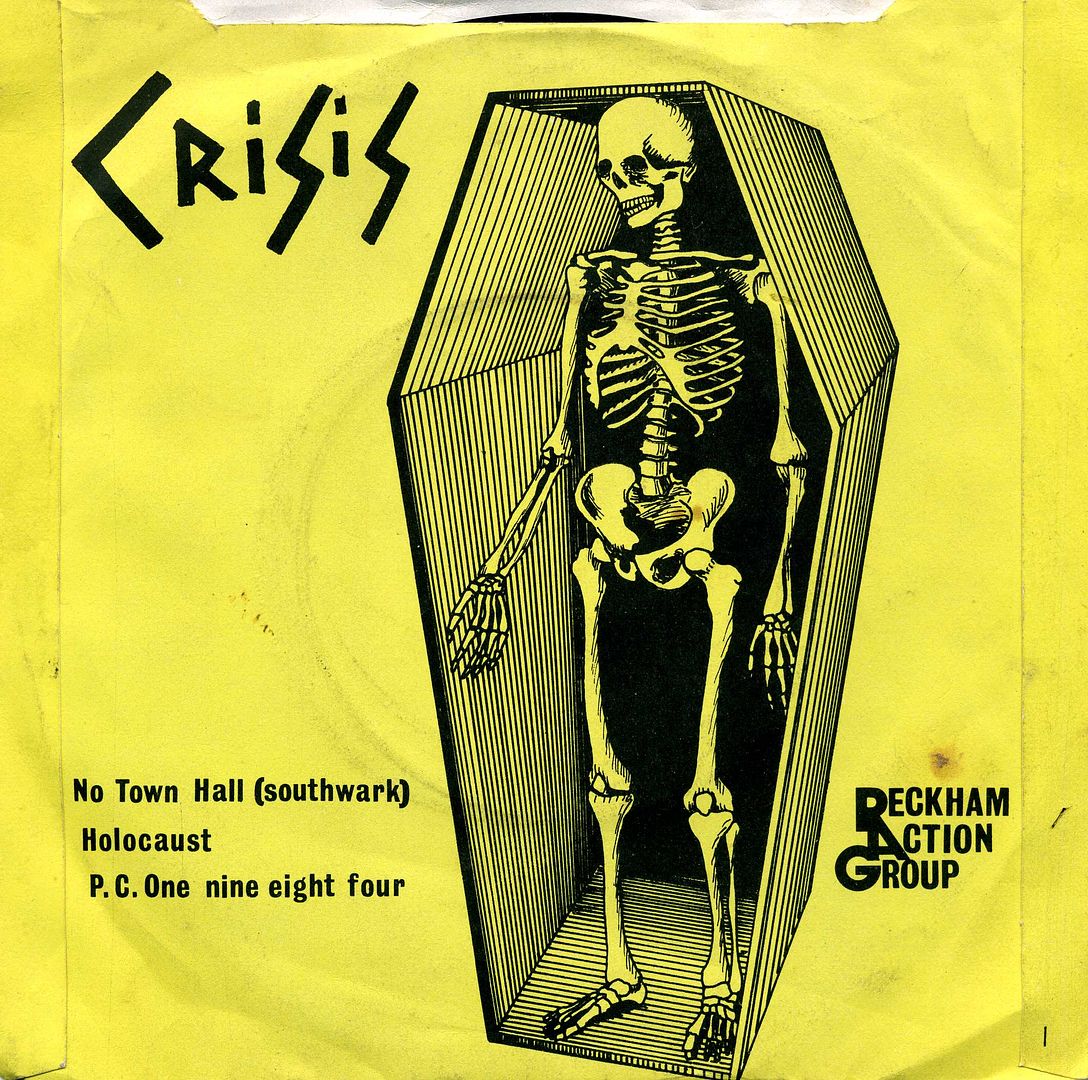

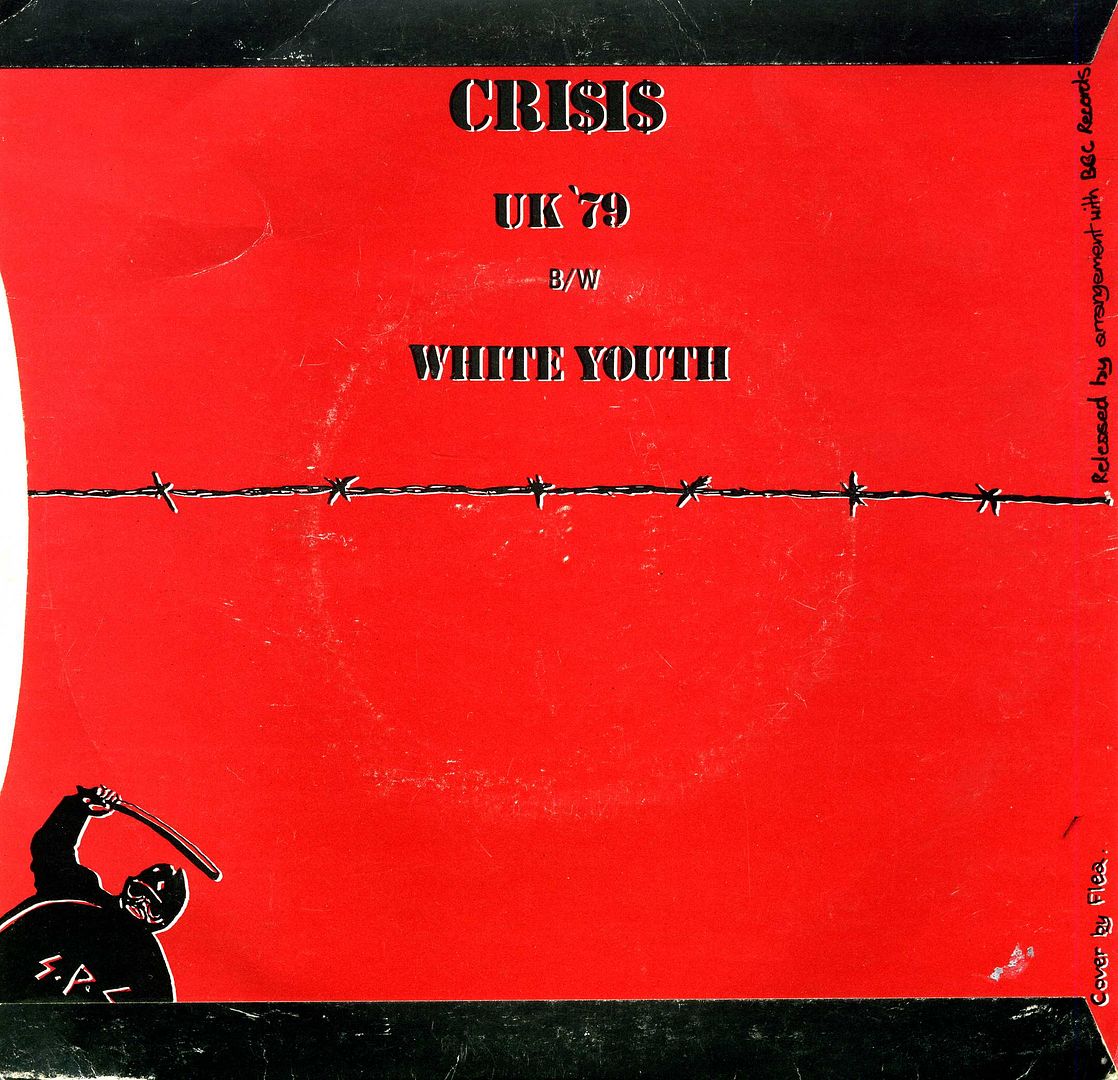

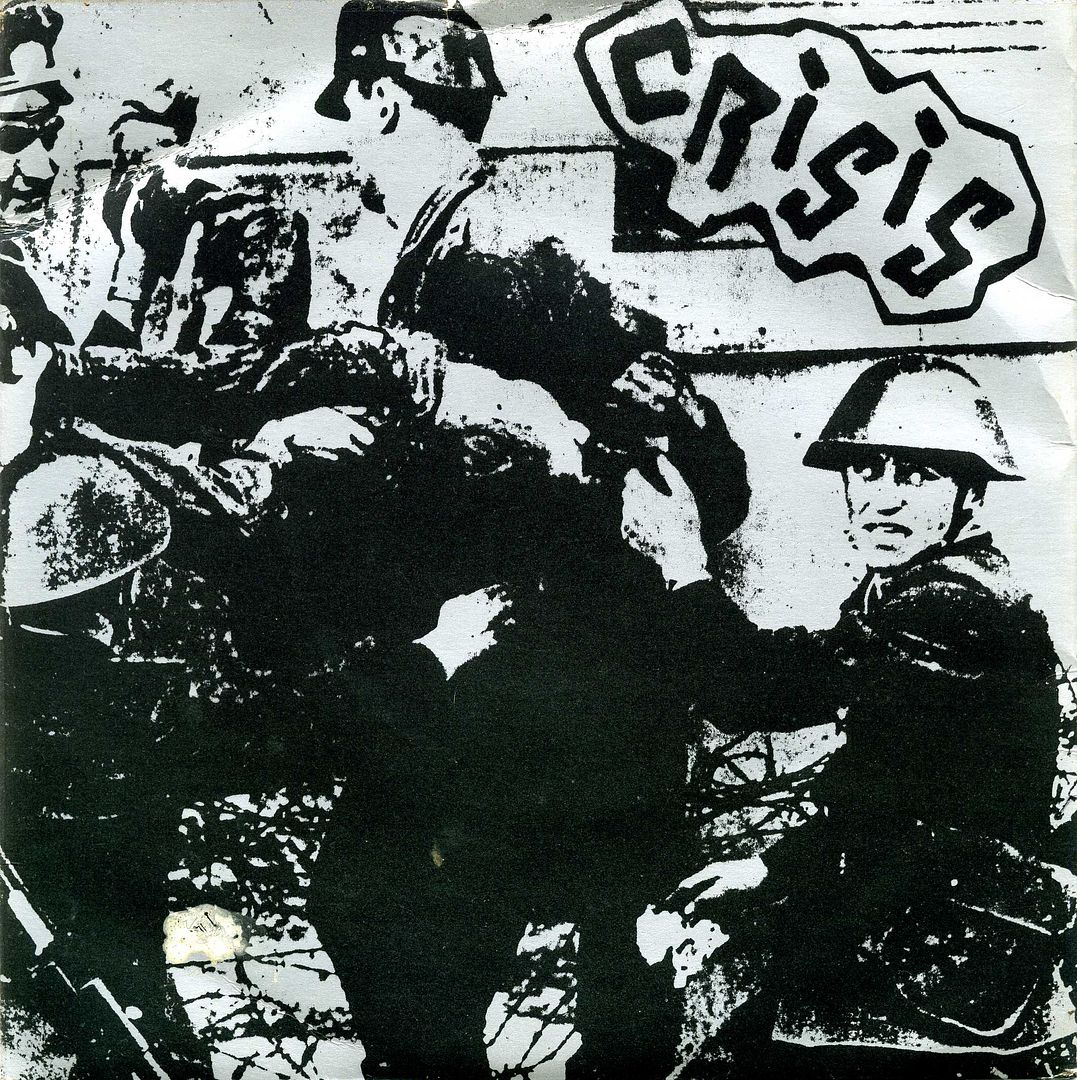

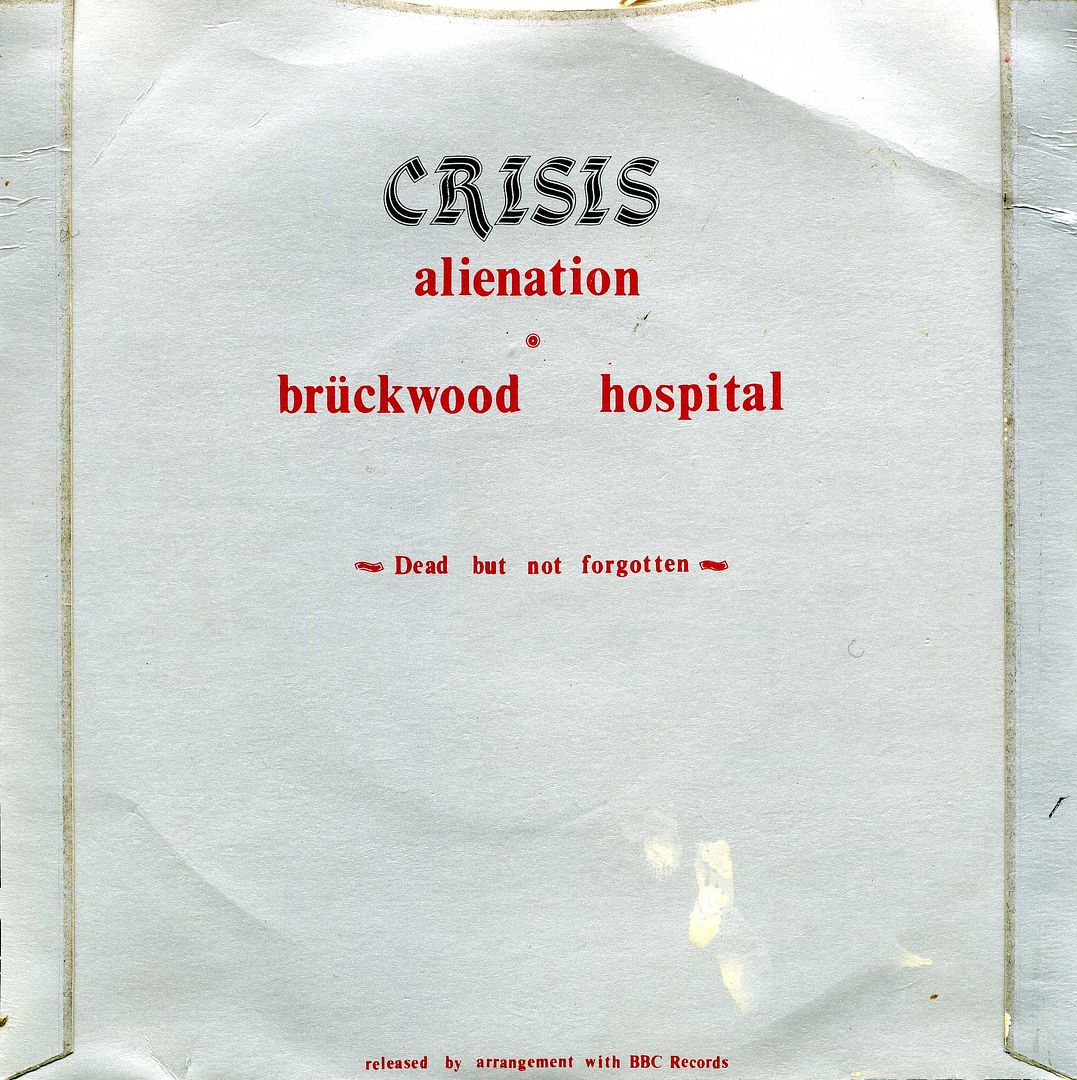

Uploaded today is the complete set of Crisis 7″ singles, all originally recorded at the B.B.C studios in London’s Maida Vale.

The first 7″ single released on Peckham Action Group records have the recordings that made up the first John Peel session that was recorded in January 1978. The two 7″ singles released on Ardcor records have the recordings that made up the second John Peel session that was recorded in November 1978. All of these tracks are magnificent. All of these tracks stand up to the test of time.

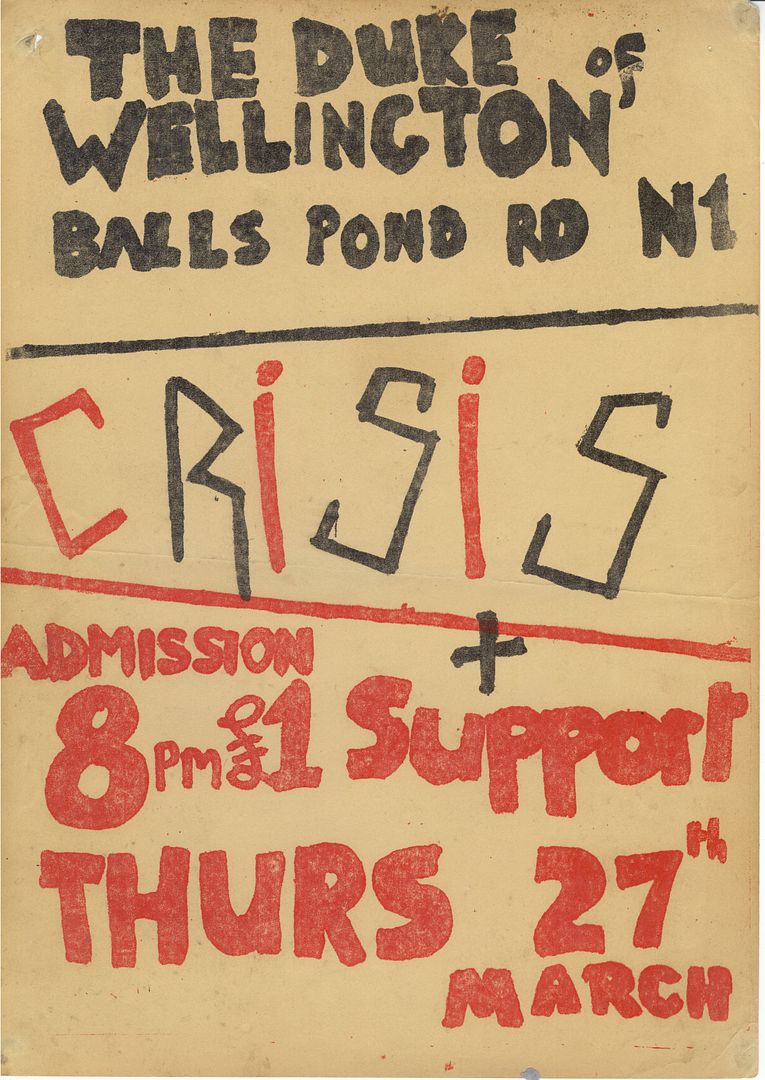

The wonderful Crisis gig poster which is the property of Stewart ‘Jellyfish’ has been placed on this post with his full blessing.

The Stewart Home reminiscences are lifted from his book ‘Cranked Up Really High’ of which you can read chapters and order a copy off his website stewarthomesociety.org.

The Douglas Pearce interview below the ‘Cranked Up Really High’ text is ripped in part from occidentalcongress.com.

As a genre, PUNK ROCK is to a large degree shaped by the response of an international audience to what, perhaps, appears to be an unending stream of records. Nevertheless, live performance occupies a peculiarly important position among exponents of this style of music. Although in my teenage years I attended concerts by a good many of the bands who have been cited on previous pages, this is not of sufficient interest to warrant detailed description. Instead, I will restrict myself to a series of anecdotes concerning one particular group, in the hope that this will give a flavour of what it was like to follow any number of bands.

Although I’d run into Frazer Towman, the first Crisis singer, at various PUNK ROCK gigs in 1977, I missed the band’s first few public appearances out of sheer laziness. I finally caught them live at their fifth gig in January 1978. I can remember walking into Woking town centre and a couple of kids of fifteen, my age at the time, trying to pick a fight. The lippier of the two bastards attempted to come on all theatrical, slowly removing his leather gloves. He didn’t like Punks, although seeing as I was dressed in a sixties tonic jacket, shirt, Levis and boots, with very short hair, I’d located myself somewhere between Punk and the re-emerging Mod and Skinhead subcultures. Anyway, when I gave the more aggressive bozo a hard shove into the on-coming traffic, these two idiots realised that despite being alone, I wasn’t going to be pushed around, so they pissed off. In 1977, and at the beginning of ’78, most ‘PUNK violence’ occurred outside concert halls, but over the next couple of years things started getting a lot more fraught at ‘new wave’ gigs.

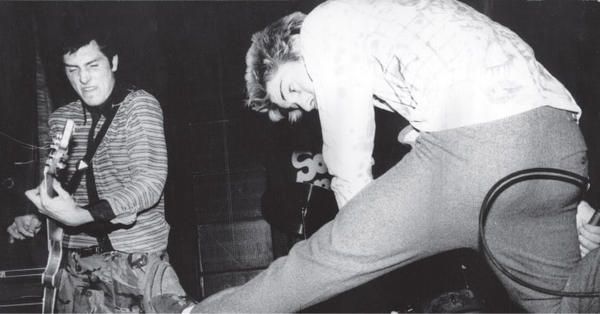

I got down to the Centre Halls and there was a real buzz because Menace and Sham 69 were top of the bill. I hadn’t been inside long when Crisis came on. I wasn’t too impressed by the drummer, Insect Robin Ledger aka the Cleaner, who looked like a twat thanks to his beard. However, once the band struck up, Frazer leapt on stage dressed in rubber trousers and a rapist’s mask and I was well impressed. The songs were basic PUNK ROCK thrash with polemical lyrics: ‘I am a militant / I am a picket / I fought at Lewisham / I fought at Grunwick / See, see the lies / See the lies civilise me / See, see the lies / See the lies can’t you see?’ or ‘Search and destroy / Search and destroy the Nazis / The National Front / Smash the National Front / Annihilate, annihilate, annihilate, annihilate, annihilate’. Of course, it turned out that the words were written by rhythm guitarist Doug Pearce (who was in the International Marxist Group) and bassist Tony Wakeford (who was a member of the Socialist Workers Party). The cream on the cake was lead guitarist Lester Jones, aka Lester Picket, who could not only play very well, he also did an excellent impression of Mick Jones taking off Keith Richards.

It didn’t take a ‘genius’ to work out Crisis had been inspired by the Clash, but what was interesting was that songwriters Doug and Tony took Strummer’s revolutionary rhetoric seriously. Although the dialectical evolution of Punk Rock was to progress in a diametrically opposed direction from that in which Crisis were attempting to push it, the group nevertheless had an intuitive grasp of what the genre was about. Before playing a key role in the promotion of the Oi! movement, future Sun hack Gary Bushell hyped Crisis as reminding him ‘of Sham a couple of months back, musically simple and muscular’ (Sounds 16 September 1978) and ‘a clenched fist rammed hard into the flabby belly of the just-for-fun music punk has become’ (‘Music To March To’, Sounds 18 November 1978). Bushell understood that the way forward for ideological Punk Rock was to rhetorically take to the streets. Crisis appeared to be doing just that, although the fact that at least some of the band took their ‘revolutionary communist’ image seriously prevented them emulating Sham 69’s chart success.

When I think of Crisis all sorts of images flash through my mind. I can remember a whole bunch of the band’s friends stealing crates of lager from behind the bar when the group played South Bank Polytechnic. Then there was the time in Brixton when Ken, the skinhead junkie, jumped on stage to wave a knife about and threaten to cut up the bastard who’d punched out his girlfriend. She’d actually passed out from alcoholic excess. Another time, Rockin’ Pete, a Teddy Boy, turned up at a Hackney gig to announce that he’d finally joined the Socialist Workers Party as though this was an act of some great significance! Then there was the performance on a side-stage at the second Anti-Nazi League Carnival when guitarist Doug P. was carted off to hospital after being electrocuted. But what I remember mainly were punch-ups, towards the end of the band’s brief life it seemed as though there were always fights at Crisis gigs.

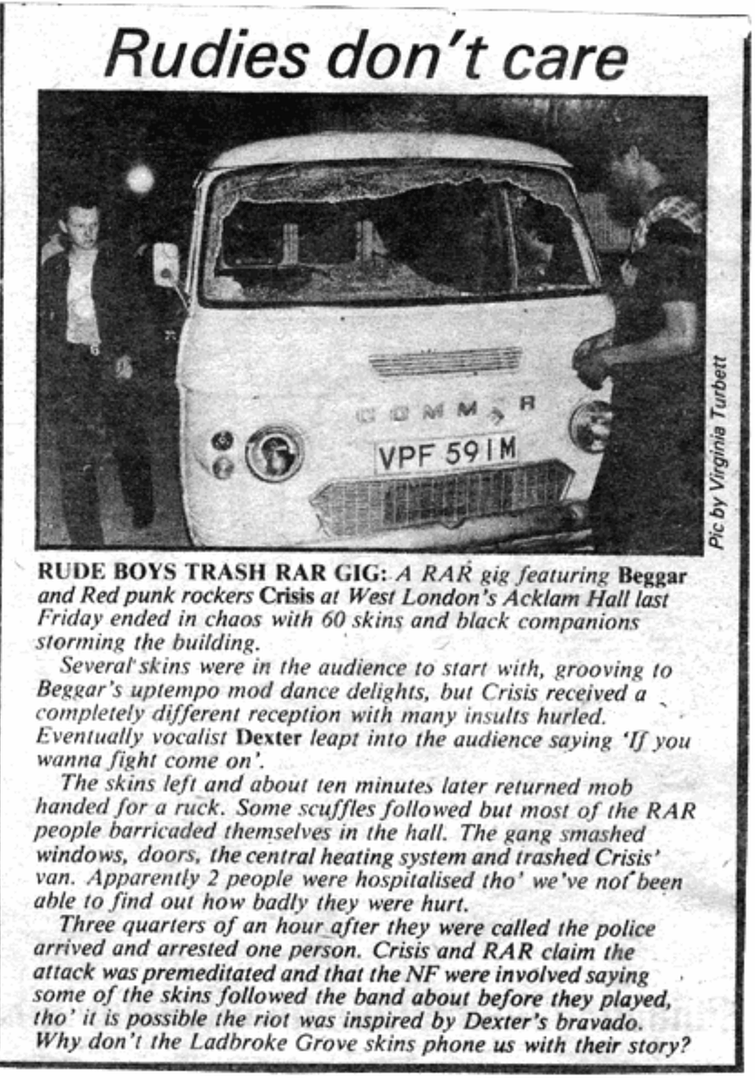

The most famous Crisis ruck was rather inaccurately reported under the headline ‘Rudies Don’t Care’ (Sounds 7 July 1979 – BELOW). An equally distorted account of the night can be found in the pro-situ pamphlet Like A Summer With A Thousand Julys by ex-King Mob members Dave and Stuart Wise, whose even sillier text The End Of Music did a great deal to help promote the ludicrous notion that PUNK ROCK was somehow ‘musical Situationism’. The actual cause of this particular ‘punk riot’ was not, as the ‘Wise’ brothers falsely claim, various boot boys being refused entry to the Acklam Hall in Notting Hill, but a Ladbroke Grove Skin who’d been granted admission, attempting to feel up a girl who followed Crisis. Taking exception to this, the chick booted the bastard in the bollocks, severely crippling the cunt. The slime-bag was too embarrassed to admit to his mates that he’d been beaten up by a bird and so he pointed me out as the person who’d given him the kicking.

I was standing in front of the stage as Crisis played, surrounded by mates, but the Ladbroke Grove Skins wrongly assumed I was on my own. When four of these twats attempted to kick my head in, they quickly found the odds turning against them as not only the audience but also the band, who’d leapt off-stage, waded in on my side. The Ladbroke Grove Skins were lucky to escape from the hall without any particularly grievous injuries. Crisis finished their set and a reggae band was playing when the skins returned mob handed, they’d rounded up sixty mates who were tooled up with hammers and pick-axe handles. This crew attempted to charge the security on the door but quick thinking Crisis fans formed a defensive line and beat them back. Meanwhile, the reggae band had locked themselves and their gear in a back room. Simultaneously, the Crisis crew threw a barricade of tables and chairs against the door while piping was ripped from the walls for use as offensive weapons.

Never inclined to stick to defensive tactics and having secured the hall. assorted members of Crisis and their hardcore following stormed out into the street to lay into the mob besieging the venue. Among the more memorable of improvised weapons were motorcycle helmets that were brought cracking down onto cropped scalps. With numerous injuries on both sides, the Ladbroke Grove Skins were eventually beaten off by the superior fighting skills of Crisis and their friends. Although the band’s transit had been trashed, with all windows smashed, the motor started and the crew loaded up the gear before piling in. Everyone thought the first stop was going to be Brixton but just down the road we spotted two of the boot boys who’d started the trouble in the hall. The driver pulled up and a score of skinheads and punks leapt from the van.

The two Ladbroke Grove Skins ran into the very hospital where those injured during the ruck had been taken for treatment. One was caught and given a kicking in front of a night nurse; the bozo had landed in the right place to have his wounds stitched up, perhaps he knew that he’d never evade his pursuers as he legged it into casualty. The other skin disappeared down a maze of corridors and, as far as I’m concerned, has never been heard of again. It should be made clear that this wasn’t punk versus skinhead violence, which was very common at the time. Although the majority of people associated with Crisis could be loosely described as ‘punks’, bassist Tony Wakeford had adopted the skinhead look before this incident, as had some of those who followed the band. Likewise, a segment of the audience attending Crisis gigs were by this time geared up in rockabilly threads. The ability of this subculturally mixed crew to see off the Ladbroke Grove Skins contrasts very favourably with the next occasion on which these boot boys besieged the Acklam Hall. Incapable of fighting their way out, Oi! band the Last Resort and their fans, who at the time were being portrayed by the media as the ultimate violent hooligans, had to be rescued by the police!

Editor note: Some interesting anecdotes on Crisis, Ripped And Torn fanzine, Tony D, Kill Your Pet Puppy fanzine, Crass, The Slits, The Clash and a host of other relevant subjects with connections in and around Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove in west London from 1978 and 1979 may be read in this Tom Vague (ex of the fine Vague fanzine) essay HERE

Other incidents I can relate about Crisis are much funnier. For example, having gone through a succession of stickmen, Crisis recruited Luke Rendall as their new drummer. Rendall was very nervous about his debut with the band, needlessly so because he was a great musician, as he demonstrated both that night and on many other occasions with Crisis and Theatre Of Hate. To psyche himself up, Luke gulped down a handful of blues and because he was speeding he played the songs far faster than usual. Two numbers into the set, rhythm guitarist Doug Pearce turned around and asked Rendall if he could slow down. The drummer shock his head and spat ‘no, mate, no,’ before launching into the next song at double speed.

One gig in Reading ran so late that after staying for the encores, the hardcore following missed the last train home. Crisis got about in a small bakery van but nevertheless felt obliged to provide transport for their mates. That night there were four people crammed onto a front seat that was designed for two passengers. So that everyone else could fit in the back, kids had to lie on top of both the equipment and each other. Coming out of Reading, the transit was stopped by some cops who’d observed that the vehicle was severely overloaded. The filth told everyone to get out and couldn’t believe their eyes when fifteen youths emerged from the rear of the van. ‘Jesus!’ a boneheaded constable exclaimed, ‘we’ve enough of ’em ‘ere for an identification parade!’

A more typical anecdote about Crisis concerns their reputation as violent nutters. Certain members of the group and some of their followers liked fighting. Whenever the opportunity arose, they’d beat up neo-fascists, and if there weren’t any Nazis about to give a kicking, they’d pick on anyone, including each other. The group’s last gig was as support act to Magazine at Surrey University in May 1980. While the gear was being set up, a friend of the band called Aggy threw food over Dexter No-Name, who at that time handled vocals for Crisis. Dexter was less than pleased and proceeded to hospitalise his mate. The Student Entertainment Officer was totally freaked out, and ran off screaming: ‘the gig hasn’t even started and already you’re beating each other up!’

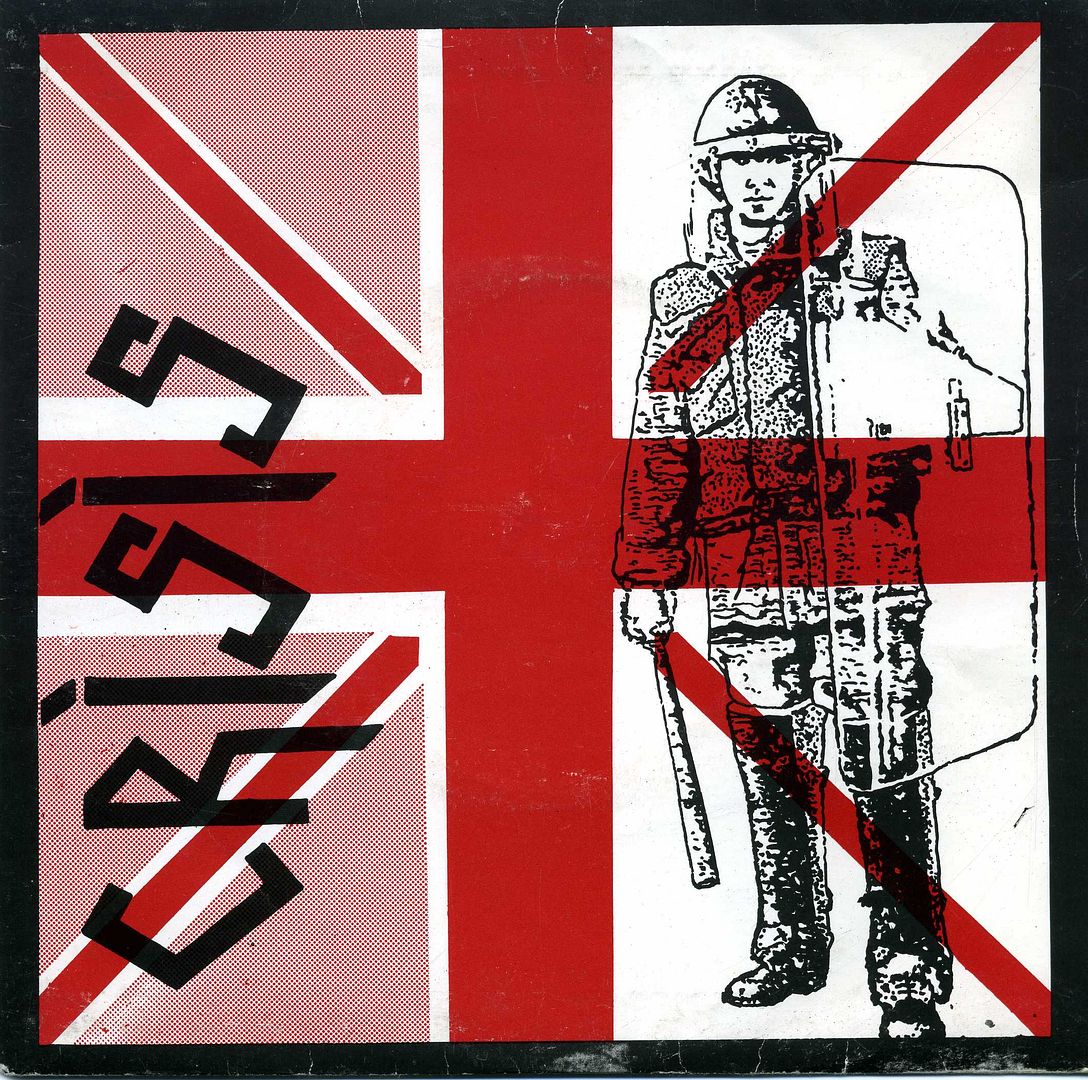

Crisis are at once typical and atypical of late seventies ideological Punk Rock at the cross-roads of dialectical change. The revolutionary commitment of Doug and Tony was at odds with the attitude of the rest of the band and their fans, most of whom weren’t interested in taking politics very seriously. The band issued two singles and a mini-album during their brief career, while one single appeared posthumously. They played something approaching a hundred gigs in Britain, mainly political benefits, and did a Rock Against Racism tour of Norway. While I went to a lot of gigs in the late seventies, I saw Crisis more times than any other band and so it is only natural for me to use them as a means of illustrating the type of activity that will reinforce the image of any given group as an ideological Punk Rock combo. Obviously, image cannot be reduced to behaviour but, alongside clothes and record sleeves, it plays a major role in how any given group is perceived by the public.

Crisis adopted a modus operandi that could be characterised as underground, after unfortunate experiences with a couple of independent labels they proceeded to put out their own product. This is a mark of their deviation from the rhetoric of Punk Rock and the beginnings of a tentative engagement with other forms of activity in which such ideals move out of the symbolic realm and take on a material reality. Some of these proclivities found a more conscious articulation in Death In June, the band founded by Doug Pearce and Tony Wakeford after Crisis split. However, this is not the place to deal with such issues. In all probability, theoretical work in this area will be left to less capable hands because I have no plans to compose a text about those tendencies whose activities were simultaneously related and opposed to the rhetoric of ‘ideological’ Punk Rock. The point to remember here is that Crisis were considerably more successful than the average band issuing their own records in 1979/80. If Crisis had been a typical Punk Rock band, they would have signed to an independent label who would have provided them with greater sales and a smaller percentage of revenue from their record releases.

STEWART HOME

In the late 1970s, Crisis marked your first appearance on the music scene, as one of the band’s two main songwriters. In the years since, your music has evolved drastically; your current project of the last two and a half decades, Death In June, is markedly dissimilar to your work with Crisis, musically, visually and politically. That said, why a retrospective “complete discography” Crisis CD now?

First of all I don’t believe that in retrospect Crisis and Death In June were that dissimilar on any of those levels. Certainly not musically towards the end of Crisis in 1980 and, the yet to be, birth in 1981 of Death In June. Visually we also had from the very beginning a look that could have easily blended into latter day DIJ with camouflage and black clothing being ‘de rigeur’. We saw ourselves as ‘Music to March To’ and so did the British mainstream press and our followers – whatever side of the political spectrum they came from. And, despite being ‘obviously’ Left wing we had many far Right followers which gave birth to a whole gamut of interesting liaisons and conversations and mutual agreements and perhaps even respect. Nothing was ever straightforward, no matter how much we might have even liked it to be. If you were a punk or a skinhead – regardless of your colour, political stance or sexual orientation – in the UK in the late 1970s that was enough to blur all and every prejudice and boundary.

Whether I like it or not Crisis forms a very important part of my personal and musical contribution to history and after six years since the last readily available compilation I thought it was now time to issue another, better thought-out, retrospective. “Holocaust Hymns” effectively replaces the “We Are All Jews And Germans” compilation that was put out by the now defunct World Serpent Distribution. And, it’s a lot better than that one, after being remastered and with more accurate track information, exclusive photos et cetera. For the first time in years I actually am enjoying listening to this moment in time. And, going by the amount of requests I’ve had for this material over recent years, so will many other good folk. Basically, there was a demand and hopefully I’ve met it.

Crisis seems to have appeared fairly early on in the whole punk “movement” of the late 1970s; what initially drew you to punk rock, and what inspired you to form your own band?

Very simply everything on all levels was horrible in England in the mid-late 1970s. When I see newsreel footage of the UK during that period I can’t believe quite how dour it all looked – and was – especially if you were from white working class backgrounds like Tony and myself! Something had to happen and it did culturally, and had a continuing significant effect on youth culture and society as a whole. I had hair down to my waist until late 1975 when I realised that wasn’t for me – that was another time – cut all my hair off and wandered around being pissed off, looking like a runaway from Francois Truffaut’s “400 Blows”. Then one day on the Tube in London I noticed someone else looking like this and then I saw a poster for a Sex Pistols gig showing two cowboys greeting each other but whose cocks were also exposed and touching, and then I heard about The Clash, and then I saw in late 1976 The Sex Pistols on an English TV show called “So It Goes,” hosted by Tony Wilson (later of Factory Records fame), and then Tony Wakeford telephoned me and asked if I had heard of Punk Rock and if I wanted to form a group. I said “yes” to both those questions and the rest is hysterical. It was a series of events that led me to Punk early on, but in comparison to the trailblazers, we took our time. Crisis came in the wake of those events and people.

Many reviewers have compared Crisis to the far-left UK band Crass, due to the two bands’ heavy use of politics as lyrical and visual subject matter within the context of punk rock. One reviewer wrote, “[Crass and Crisis] both signaled the end of punk as fun, spontaneity, massiveness and anarchy (as a way of feeling). In this new ‘new wave’ of punk, punk was seen as a tool of protest… Crass, Crisis and the bands they bred became the new puritans. [The Crisis track] PC1984 might as well have stood for politically correct 1984 as they told us the truth about the world and what our part should be in it according to their rules. The truth was black and white…the enemy obvious…the police were the fascistic army to dominate the workers.” Do you think this is a fair criticism, and does is reflect your actual aims for the band at the time, or more of how the band was perceived by the press and fans? Do you look back on your time with Crisis as being “fun,” or was it something else, as the above quote alleges?

Crisis and my experience of Punk Rock in Britain/Europe was anything and everything but “fun” and this sort of idea comes from people who were either not there at the time, or were and have an axe of some kind or another to grind about their own experiences with Crisis. The years between 1977 and 1980 were some of the hardest of my Life and they certainly contributed to Tony and I wanting to destroy the group in 1980 and head for sunnier pastures artistically, culturally, and whatever else we could find. However, we couldn’t deny our cultural imperative at the time. We were in Crisis unashamedly left wing or, at least trying to be, and wanted to be taken seriously politically. Which we were! So seriously in fact that when celebrities found out we were part of the Anti-Nazi League or Rock Against Racism benefits they withdrew their support. Names like the author Keith Waterhouse, TV compare Michael Parkinson and Football coach Brian Clough immediately spring to mind. They publicly withdrew their support because of Crisis! Crisis were referred to as “Red Fascists” almost from the outset, which seemed to confuse and upset some folk and also endear us to others. They were “interesting times.”

And as regards any comparisons to Crass: They were not contemporaries of ours, I don’t remember any comparisons at the time and I think we only became aware of them after the demise of Crisis and at the beginning of Death In June in the early 1980s. Certainly to us then they seemed like the guys at free festivals dishing out lentils and orange juice to those on a bad trip when they realised they had been left behind, there was no one left at the festival anymore and in order to catch up with ‘the kids,’ cropped their hair, wore black and decided to form what was I think akin to the Hari Krishnas; a caricature of a punk group, and do their bit for those who weren’t there in the first place. I’m sure their hearts were in the right place and I love lentils and orange juice, and they did indeed invent their own particular version of Punk but,…. “Do they owe us a living?” Of course they fucking DON’T!

Following the dissolution of Crisis, members of the band went on to form or join acts such as Theatre of Hate, Sol Invictus, Sex Gang Children, and of course your own Death In June. Are you still in touch with any of these other ex-Crisis members, and if so, what is your perception of their post-Crisis work?

Even before the end Luke Rendall the last drummer in Crisis was basically headhunted by Kirk Brandon who was then in a group called The Pack. They went onto to form Theatre Of Hate which I quite liked and I saw a few of their early shows in the London area. I think my best memory was being backstage when Boy George was having a fit about some bloke giving Kirk the eye and how he was going to beat the shit out of him! This was before Culture Club and I have to say I think fame really became Boy George who seemed more like a transvestite psychopath that night than a Karma Kamelion. It also evidently made him lose interest in Kirk! I heard a few years ago that Luke had been murdered.

Lester, the lead guitarist of Crisis, went on to form a group called Car Crash International with members of the Sex Gang Children but I can’t recall what they were like and am only aware of one 12″ single that they put out.

Our two roadies Martin and Flea went on to work with The Clash and Big Audio Dynamite and Flea who designed some of the original Crisis record sleeves was even in several Big Audio Dynamite videos. I don’t know how much input he had in their creation but he was a very talented artist and all-round interesting guy.

Sol Invictus, of course, came out of Death In June not Crisis.

With the exception of Tony Wakeford I’m not in contact with anyone from those Punk days.

In the years since Crisis, you seem to have moved from the realm of politics to that of aesthetics. Conceptually, Crisis seems to have been a very direct, literal and “instructive” project in nature, in the sense that the songs were clearly about (and commenting upon), something specific, and urging the listener to think and feel about things in certain ways. Because of this, Crisis could really only be interpreted one way – literally and at face value – while your subsequent work with Death In June seems to me as being almost the opposite of that sort of approach; it’s rife with vague allusions, double meanings, and open-ended readings. In short, Crisis was a very matter-of-fact thing, while Death In June is a much more nebulous and poetic project. Assuming such an interpretation of your work is accurate, was this shift in approach a conscious decision on your part, or did it happen as a part of a gradual process?

Even though we might have thought what we were writing/singing about was “specific” and “straightforward” it was soon interpreted as anything but. The song ‘White Youth’ is a prime example. We performed several times on the back of a lorry on demonstrations throughout the South of England / London that were organized by The Right To Work campaign. Crisis would play for up to seven or eight hours, with a few breaks in between, entertaining the people who had been marching in protest to their unemployment which was then rife in the UK. It was our equivalent to The Beatles slogging their way through similar set lengths in some sleaze pit in Hamburg in the early 1960s. Whilst they had their happy memories of the Reeperbahn, I have happy memories of stopping traffic crossing Tower Bridge in London playing “UK 79″ and “Holocaust”. We wrote with that marching rhythm in mind the song “White Youth,” which we thought was about ‘unity and brotherhood’ [the song ends with the repeated verse, “We are black, we are white – together we are dynamite!”], but much to my surprise some smartarse in the New Musical Express was soon saying that it was a white supremacist anthem. There’s no pleasing some folk is there! That was key in realizing that no matter what you wrote if it was any good it could be interpreted anyway, anyhow, anywhere. A Death In June prime directive!

chris L

March 20, 2013 at 5:41 pmTop post as always ! I’ve got some great Crisis interviews from the RAR paper “Temporary Hoarding”. Will try to get em scanned + emailed to you.

Rob

March 22, 2013 at 3:12 amThe eerie guitar riff and relevant subject matter of ‘Holocaust’ (the then rise of the extreme far right) stood out like a sore thumb on John Peel’s radio show in 1979. A lone politicised blast months before the first anarcho rumblings…..

marko

March 24, 2013 at 11:27 amOne of the best books, written by Home, about the that era of the punk movement

Chris Low

May 2, 2013 at 4:38 pmIf by any chance anyone has a copy of this they want to sell please contact me via KillYourPetPuppy. Lost my copy years ago and am happy to pay a healthy price but simply can’t afford the money it tends to go for on Ebay these days. Thanks.

Chris Low

May 2, 2013 at 4:39 pm@ marko. If you mean Home’s “Cranked up really high” book I couldn’t agree more. A fantastic, fascinating – and in places very funny – read.

Steve

May 3, 2013 at 6:48 pmThe full text of Cranked Up Really High is available on Stewart Home’s website.

Steve

May 4, 2013 at 11:26 amHere, to be precise:

http://stewarthomesociety.org/cranked/content.htm

Nick Hydra

May 24, 2023 at 1:32 pm“The cops don’t even carry guns”

Massively influential on the Anarcho scene despite being on the Trotskyist end of the political spectrum. If you listen to live versions of Conflict’s ‘1824 Overture’ rather than the recorded version which omits the original intro, or early Flux vocals you can really hear Crisis.

Great cover design too.