Firstly I would like to thank P W Barnabas for allowing me to place the Halloween story onto the Kill Your Pet Puppy site exclusively.

P W Barnabas sent this story to me originally on the evening of Halloween 2012 and I now have the great pleasure in placing the story onto this post so that browsers may read it.

Thanks to Ferelli for the use of his art on this Halloween post.

INTRODUCTION

There are no ancient witches casting spells in fire and darkness. Their screaming hatred does not crackle among the night-time, scarred black trees.

There are no madmen, indestructible and merciless, standing in the broken midnight door, and their breath clouding white in the cold moonlight, their wicked eyes searching the horrors scratched inside their solitary skulls.

There are no ghosts waiting the long years, with bony fingers feeling out to grip, with steely knives flashing out to slash the bubbling life from the hated living.

All there is, is three University Professors trying to solve the problem that has puzzled the highest and the lowest since time began.

‘What happens when we die?’

IN THE BEGINNING

“Otto, we can’t make this change. I know the danger of the new heresies, and even the possibility of the Pagans gaining more power. I know all this, but we can’t make a change of this magnitude, Otto. The Bishops will never accept it…”

The man sitting at the table lifted a heavily ringed finger to silence the speaker. When he was sure the other man was listening, he spoke.

“My friend, if you are going to disagree with me, I suggest you address me as ‘Your Holiness’.”

“But…but…”

Pope Otto raised his eyebrows at his friend, the Bishop.

“Julian, let me make this clear: the thirty-first day of the month of October is perhaps the most important day in the Pagan calendar. The energies that it inspires must be used for the purposes of Mother Church. We must take this day from the enemies of Christ. Yes?”

Julian realised that Otto’s mind was made up. Otto was a clever and resourceful man. He intended to leave his mark on the Christian calendar. Julian might voice his objections in private, but he was not going to stand against Otto, the most powerful man in the Christian world, and the direct representative of God on Earth.

The Christian world at this time was a mess of heresy. Groups led by madmen, priests, soldiers, ambitious rulers and all sorts, were springing up. The Holy Mother Church was losing the struggle for the souls of the people. The last day of October was the end of the Celtic year. It was the Feast of the Dead. The sun entered the gates of Hell on this day of the Celtic calendar. Evil spirits could escape, and roam the world doing mischief.

“Julian, my friend, sit down, please sit down. I will tell you what I propose to do. I will make an order allowing three Masses to be said on this day, the same as on the Day of the Birth of Christ. There will be a special Mass said for the dead. It will be a day of prayer for the souls of the Saints and Martyrs. The people will forget that it was ever a part of a different calendar. This is what I will do. Will you stand by me?”

The Bishop drummed his fingers on the table, thinking hard. He feared for the souls of God’s children on earth. Did the strength of Mother Church lie in its stability, or in its flexibility? He did not envy Otto. The Church was weaker than most people realised. The massive walls of the Abbey were only walls of stone. The wealth of the Church was only as safe as the strength of those to whom it was entrusted. The Authority of the Pope rested on the support of the Bishops.

“What will you call this festival, Your Holiness?”

“Please, Julian, call me Otto. It will be the Festival of All Saints. It may also be known by the Hallowed Names of the Saints and Martyrs. Yes, ‘All Hallows’ Eve’.”

“We are tampering with forces we do not understand,” thought Julian. His fears would echo down the centuries. Difficult and dangerous was the world of God’s children.

The two men sat in silence.

THE DISCUSSION

“We are tampering with forces we do not understand!”

There was silence in the room.

The three people sitting in the warm, subdued light looked at each other to see who would break first. The silence lengthened.

Professor Sarah Goring was the first to give in.

Her burst of laughter echoed round the room and set the whisky glasses on the tray ringing in sympathy. Her companions collapsed in helpless laughter. They each sat in their comfortable armchair, the firelight shining on their faces, unable to get the hackneyed phrase out of their minds. No one could remember which particular ‘Frankenstein’ film the line was from, but the more they thought about it, the funnier it seemed.

Finally, the three friends fell again into a silence, disturbed only by the crackling of the fire, and an occasional giggle which threatened to set them all going again.

Despite the laughter, there was an atmosphere of tension between them. Professor Goring’s ideas might have come from one of the flood of cheap horror movies which filled the cinemas in the 1960’s, and not from the mind of a respectable university Professor.

But, somewhere, a nerve had been touched. The room was full of ghosts – full of possibility.

“Sarah?”

“Yes, Paul?”

“What is Halloween? I mean, what is it apart from that dreadful American habit of encouraging kids to dress up, knock on doors, and risk my boot up their backsides…?”

“And that oppressive series of films of the same name, which” interrupted Professor Ketley, “even on my loneliest Saturday night, I manage to avoid!”

“Spoken like true Protestants,” laughed Sarah, picking up her glass and watching the swirl of alcohol above the surface of the pale liquid. She filled her mouth with whisky. The fumes, evaporating in the warmth, caught at the back of her throat, and threatened to start her coughing. She waited. The feeling subsided. The taste of moorland and granite rock, and the hint of a warm Highland fire on a cold, rainy night filled her with a sense of well-being. She settled deeper into her chair, in no hurry to speak and waste the pleasure of the fine spirit.

“Halloween, my dear Paul, ignorant as you are of all the finer points of Catholic theology, is the shortened form of ‘All Hallows’ Eve’.”

“That doesn’t make me any wiser,” said the engineer.

Sarah snorted, and continued her explanation in her favourite, and most annoying, teaching voice.

“We poor Catholics believe that the souls of the dead go to Heaven or Hell…”

“Or some place in between…?”

“Yes, Paul, Purgatory. The sinners, who haven’t condemned themselves to Hell for all eternity, go to Purgatory, where they are not lost, but are not saved. They suffer, but they have the hope of finally being released and going to Heaven…”

“I don’t believe in Heaven,” interrupted Professor Ketley.

Sarah looked across at the mischievous twinkle in the Professor’s eye, and said,

“George, can we limit the conversation to Christian theology? If we have to explore the finer philosophical points of your Jewish fore-fathers, we’ll be here all night!”

“We’re here all night, anyway,” said Paul, smugly.

“You know quite well what I mean, Paul. Listen: once a year, all the poor souls in Purgatory are freed for one night to wander the earth. Prayers for mercy for these tormented souls, made by the living, may be heard and may shorten their suffering. The souls of those in Purgatory have a chance of eternal bliss if only one of their living friends or relatives – or some other generous person – prays for their salvation. Haven’t you ever heard of the phrase, ‘don’t speak ill of the dead’? Halloween, and the possibility of the wishes of the living being able to affect the dead, is where this saying comes from.”

Paul looked out of the un-curtained windows at the night. The firelight sometimes caught on the branches of trees near the house. He moved uncomfortably in his chair. His whisky glass balanced, swaying and forgotten, on one of the padded armrests. He felt a chill run down his spine. He did not know why, but Catholicism always managed to strike a raw nerve in him. It was as if his own liberal, ‘Church of England’ upbringing had allowed him to play at religion, to convince himself that God, if he existed, was like a kindly, retired Colonel, sometimes indulging in fits of irritation.

Catholicism was altogether more dark and serious, more sensual, more hellish. The Protestants looked after the consciences of the middle classes, while the Catholics inhabited the land of the sick and the dead.

Sitting there, safe but uneasy, he imagined a night populated by desperate spirits, hearing their wailing, whispering voices in the wind and the rustle of leaves.

THE PROPOSAL

“Paul. Paul. Hey, Paul, pay attention,” said Professor Ketley, in a theatrical whisper, winking at the woman opposite him. “I think you’ve done well to start daydreaming. You’ve missed most of Sarah’s ‘tale of terror’. However, it seems to me that she is finally going to tell us precisely what is on her mind. Sarah will explain the mad project she has invented, and say how she needs our help.” Ketley sank back in his chair and adopted a pose of intense readiness.

The fumes of alcohol had not clouded Professor Goring’s mind. She judged that the time and the tone of the conversation were just right.

“Gentlemen, I want to hold – to trap, if you like – the soul of a dead person. Not for ever, but just long enough to prove that the spirit survives the body.”

Neither man was foolish enough to show his surprise. Sarah might be a little mad, or even just enormously bored with academic life, but she was a powerful force in the life of the university. Her mix of theology and philosophy had won her the respect of many of the great minds in her college. Ketley’s own speciality in the area of probability mathematics, and Paul’s brilliant work in the creation of remote electrical fields, meant that all three were working at some frontier of thought or science.

Ketley took a deep breath.

“How?” he asked.

“George,” replied Sarah, sitting forward on the edge of her seat, “If I wanted scientists to invent an anti-gravity machine, the first thing I would do would be to fake some film of one working. Once people believe that something is possible, they stand a better chance of inventing it. The same here. If I free my mind from the impossibility of doing what I want to do, I might find a way of doing it.”

“You mean like the Zen idea of ‘each journey starting with the first step’,” said Paul, realising immediately that she hadn’t.

“Meaning that each journey starts with the idea that the journey is possible!”

Sarah looked at each man in turn to make sure she had their full attention, before continuing.

“There is one month to go before the night of November 1st, Halloween. In that month, I want to create with you two gentlemen, a machine which will attract, hold, and make visible, the soul of some dead person in Purgatory who is allowed to roam the earth on that night each year…”

“What do they get out of it?” asked Paul, a little facetiously.

“I will pray for their salvation,” replied Sarah, simply.

Both men experienced the same thing at the same time. There was no escape. Sarah might have wild ideas, but her grasp of psychology was perfect. The word, ‘NO!’ screamed in each man’s head, but the damage was done. Like great engines starting to turn, their minds engaged. There was no stopping them. If there was a way to create such a machine, they would find it. The search would fill their dreams and their waking days. The desire had been born.

After all, what more original work could they do than help prove, once and for all, the existence of an afterlife?

THE MACHINE

Paul worked swiftly in the weeks that followed. Professor Goring was right. Once the mind was free from the sense of impossibility, a whole landscape of possibility started to grow. How could a soul exist, once you assume that it did exist? Where does it live and move and have its being?

It would not be true to say that Paul had any definite idea in his head. It was more a feeling, a sense that an area where he already worked had a quality that might be worth exploring. He smiled. The accuracy of his intuitions was legendary in the small, enclosed world of the university, and perhaps in some other centres of specialised research.

“Better to be born lucky than rich, they say!”

The figures pouring from the neat point of his pencil onto the notebook looked cramped and tense. He spun the pencil up into the air and caught it absentmindedly, before jamming it behind one ear and walking over to the blackboard which covered one wall of the room. He picked up a piece of chalk.

His equations and sketches wandered erratically over the wide expanse. Many of the equations had a terribly strong desire to vanish to zero, or to explode uselessly to infinity. Determined, he wrenched them back from the brink, substituting and modifying, trimming and persuading. After hours of intense work, the flamboyant expressions tailed off towards the bottom right hand corner of the board.

Paul snapped a piece of chalk between his fingers and flicked the ends away with a grunt of disgust. White chalk-dust hung in the air, lit by the sunlight streaming through the windows. Paul watched the particles suspended in light. He blew a sigh of fatigue. The dust cloud suddenly tumbled and whirled. The scientist saw and didn’t see. He could almost hear the click in his head as the thought formed. He had spent days looking for some way to attract Dr Goring’s ‘ghosts’, knowing nothing about what they might consist of. Then he realised what the dust symbolised.

What if…? What if…?

Paul allowed himself the pleasure of reasoning out loud:

“Forget ‘attraction’. Think about ‘repulsion’! Only specific things are attracted by other specific things. It’s too ‘specific’! If you want to hold something in, you build a wall round it. The wall will hold many different sorts of things in – from microbes to elephants, from air to heat to light, from pigs to protons.

“Don’t worry about what a ‘spirit’ might be made of. Just erect an enclosure that will repel and contain as many different ‘essences’ as possible! That’s why my equations were trying so hard to disappear to nothing. The amount of energy involved with a ‘ghost’, ‘spirit’, or whatever these things are, must be tiny, almost nothing. I was looking for the solid chalk ‘ghost’. I must look for the ‘ghost’ of chalk-dust!”

The engineer let go a string of expletives in the best possible humour. A class of particle-physics students passing in the corridor were shocked. They wondered whether their parents, who had spent so much money to have their precious children educated at the great university, would really approve. They hurried away like a flock of startled geese.

THE TELEPHONE

“George?”

“Paul.”

“Look, George, I don’t know if you’ve made any progress.”

“Progress?” Professor Ketley felt a shade of resentment pass through him at the thought that Paul might have found some way of dealing with this crazy problem, which had haunted them both, day after day.

“You know that I’m a ‘nuts and bolts’ man, George. I was so busy thinking about how to attract Sarah’s ‘ghosts’, that I’ve only just realised that a better way might be to think about holding them in, and concentrating them into an enclosed area. If I tried to create a machine that would throw an ‘energy fence’ round a specific area, the energy force which would repel and contain things that science already knows about, might also have the same effect on things that science doesn’t know about.”

There was a pause. Paul could hear the other man breathing at the end of the line. He sensed that George was trying to digest the implications of what his friend had just said. The pause went on.

Finally, there came a single word, “Right.”

“Right what, George? ‘Right’, that’s a brilliant idea, tell me more? Or, ‘right’, this man is crazy!”

“The former.”

Paul always had to work out the ‘former/latter’ thing from first principles.

“Right.”

“Right what, Paul?”

“Professor Ketley, I would like you to give some thought to the probabilities and possible energy balances of these imaginary ‘ghosts’. I would like to make our machine as effective and tuned as possible.”

“That goes without saying, my dear chap!” said George, in the tones of a British fighter pilot in a world war two film. “I’ll get back to you.”

“George?”

“What?”

“What do you think?”

“What do I think, Paul? I think it’s fucking brilliant!

SOULS AND ENERGY

Ketley sat at his desk in his rooms at college. Outside, the ancient stonework shone grey or sand coloured in the cold light of the short afternoon. Soon, the light would go from the sky. He would feel that brief but deep depression which always came at the end of another day. He picked up a dart from a multicoloured collection in a large jam jar, and flung it at the circular target hanging from the back of his entrance door. His students were always a little afraid, when they entered for a tutorial, that they might be stuck with a dart. George made no attempt to put the dart-board anywhere safer. Eccentricity was expected, almost demanded, from the higher ranks of the teaching staff.

The Professor hardly noticed where his dart landed. Two words kept bouncing around in his brain. They danced and swirled, played and fought, like two nymphs from a particularly syrupy section of Disney’s Fantasia. ‘Soul’ and ‘energy’. Energy and souls.

The problem that Paul had set him was not to find the energy form that a soul might have. No one had ever got close to doing that, although some colleagues from a certain disreputable Californian university had boasted that they had succeeded – he doubted it. The West Coast was where all the US lunatics came to rest before they fell into the sea! His problem was to find what the energy form probably was.

Piled on a table were stacks of books about the Occult. George had hoped for some clue, some starting point from which to predict the possible qualities that ‘ghosts’ or ‘spirits’ might share with the more measurable world.

George knew that most of the material world followed the play of possibility and probability. On the level of ‘real’ matter, nothing was absolute – it only looked that way to the untrained observer.

The minutes ticked by. With a sigh, George swung his chair round to face a decidedly ‘untraditional’ computer. It was brand new, powerful, and still smelled of new electronics and plastic. It blinked to life. With the unexpected dexterity of a ‘touch-typist’, George set up a simple but very specific mathematical expression, and sent it to play in the mysterious digital world of electrons.

“Time for tea,” said Professor Ketley, strangely tired by the afternoon.

THE PRIEST

It was the evening of the next day. Earlier on in the day, Professor Ketley had enlisted the help of several of his students to take all the books on the Occult back to the college libraries from which they came. He offered no explanation for his strange reading matter. The students talked quietly to each other and shot him meaningful glances when they thought he wasn’t looking. Ketley smiled, and remembered how conservative he too had been when he was their age.

As he drove through the clinically bright streets, under the expensive street lights, he thought how easy it was to miss the obvious solution to a problem. His race to the Occult libraries in the university was like a man with an illness going straight to the faith-healers, rather than visiting his doctor.

Ketley had phoned an old friend from his student days. The man was now a priest attached to one of the largest Catholic churches in the area. He had made an appointment to meet him that evening. Ketley crossed the old town. He thought about this friend, John, and about their time as students. It was an unlikely friendship, the intense religious belief of the short and dark-haired son of a factory worker, against his own glib and self-satisfied wanderings, fuelled by whatever drugs he could get his hands on. Ketley smiled to himself at a thought that had just occurred to him.

“We were a bit like George and the Dragon: John was Saint George, while I was definitely behaving like a dragon, gobbling up maidens and setting fire to my college rooms.”

The church stood tall and massive in the distance. The priest’s house next to it was a ghastly Victorian monster. Professor Ketley swung into the drive and pulled up before the porch, which was lit only by a weak and dusty bulb. A bell rang shrilly in the distance when he pushed the brass button. Footsteps approached, and the hall light came on. Ketley thought to himself how he hated the government campaign to ‘switch off’ unneeded lights to save energy. His own rooms blazed with light, night and day.

“George, it’s good to see you. Come in!” The man who spoke was even shorter than George remembered. The priest stared up at him as he took his hand and shook it warmly.

“It’s good of you to see me at such short notice, John. I have to confess that this isn’t a purely social call. I need to see a ‘specialist’.”

The priest glanced searchingly at his old friend, looking for signs of illness. People like Professor Ketley only felt the need to involve themselves in religion if something terrible was occurring in their life. He saw nothing. He shrugged and led the way into his study. The smell of old leather-bound books and wax polish filled the room. A bottle and two glasses stood waiting on a side table.

“Sit down, my friend. I hope you don’t mind me sitting at my desk. I have to confess that it’s the most comfortable seat in the house. What can I do for you?”

George paused, before deciding to get straight to the point.

“What can you tell me about souls in Purgatory, John?”

A slight smile appeared on the priest’s lips.

“Is this a personal enquiry, George?”

Both men burst out laughing.

“No, no. I’m not checking up on my future accommodation! Do you know Dr Sarah Goring of the university?”

George noticed a troubled look, almost of shock, appear for a moment on the priest’s face.

“Yes, I think I met her at one of those interminable college suppers. She seems very … bright.”

“John, she is. You remember Paul too, that crazy engineer who was always inventing things? Well, Sarah has asked us to help her with a little experiment.”

“Yes?”

“She wants to prove the existence of ‘souls’.”

The priest paused, leaning back in his chair and twiddling his thumbs with his fingers locked together.

Again, George thought he saw some intense emotion in the other man.

“And how does she propose to do this?”

Father John was quite accustomed to the occasional studies being undertaken at the university theology department, and in the groups of strange and/or mad people who always seem to gather on the edges of the great centres of learning. But he was also aware that Paul, George and Sarah did not quite fit into this category. He did not know why, but he was suddenly filled with a deep sense of trouble ahead.

THE LESSON

“Well, John, as far as I understand, Sarah wants to prove the existence of the ‘soul’ by – how can I put it without sounding callous? – by capturing or holding a soul – this is mad – by trapping a soul on the night of Halloween, when she believes – and you probably believe – that the souls of those in Purgatory are free to roam the earth. I know it sounds stupid. When I put it into words, I feel like someone in a cheap horror film!”

Father John said nothing for some time. Ketley sensed the unease in the other man, who stirred occasionally in his seat. The glass of brandy before him was left untouched. Finally, his old friend sat forward and placed his hands flat on the worn, polished surface of his desk.

“George, we’ve known each other for a long time. You’re a liberal, educated man. You’re talking to a man who believes in many things that you find ridiculous. But you should understand this, before we talk any further: my faith requires me to believe certain things. You have the privilege of being able to pick up and discard ideas as you wish. You are safe in the all-embracing arms of the university. You can … er… experiment with belief.

“I am different. Not only does my faith require me to believe, but my whole life is structured around these beliefs. People on the outside do not realise the consequences of this. Not only are these beliefs very real to me, but they bring me in contact with energies – with forces – of which most people know nothing.

“You say you want to ‘trap’ souls. I don’t believe you have thought about what it means if this is actually possible.”

Ketley felt as if the air in the room had cooled suddenly. He realised that his own easy-going, academic world did not hold true here. In some ways, this was the real world.

The priest saw his discomfort.

“Let me tell you a little anecdote, which I think is true, but even if it’s not, it’s a good example of – how can I put it? – of different levels of reality.

“You like classical music, don’t you? Beethoven?”

“I prefer Mozart, but yes, I listen to Beethoven.”

“Beethoven was sitting in a field one day. He had just invented a little sequence of four notes. Nothing special, but the notes just kept running through his head. At that moment a friend of his came up to him in the field. It was a nice day. He was out walking. Now, this friend owed Beethoven some money. Beethoven said that he thought it was time his friend paid back the money. The friend asked, ‘Must it be?’ and Beethoven replied, jokingly, ‘Yes, it must be’.”

Father John beat a short drum roll with his fingers on the surface of his old desk in a way that George knew well, before continuing.

“Beethoven thought about this incident. He thought about the little question and answer. From this tiny seed, from this idea and the four notes, Beethoven created one of the most profound and moving pieces of music ever written about the nature of life.”

Ketley sipped his drink. The priest’s words were not lost on him. The parallel was obvious. His own question and answer were, ‘You want to trap a soul?’ ‘Yes.’ The talent at his disposal was three of the most acute minds in the university. All at once, the comfortable, middle-aged college professor was filled with fear. For the first time in his life, Professor Ketley sensed the nearness, the presence, of death.

OCTOBER

How did they do it? The time was so short. Fortunately, the university allowed plenty of space for academics who were suddenly caught by a new idea. They could pursue it without having to worry about their college commitments. New ideas were the life-blood of the university. The teaching duties of the two men were picked up by their colleagues. They were free to work on their new project. Rumours sped round the ancient buildings. The one most believed, was the idea that there was an attempt being made to ‘raise the dead’. This speculation brightened the life of many a bored, tired academic.

They were lucky. Paul found that most of the equipment he needed was already available in one form or another. He and Professor Ketley worked long and hard trying to ‘tune’ the equipment, to focus on that strange, elusive probability barrier between existence and absence.

They slept little. They grew close through the long hours. Often, they would be found deep in hushed conversation over a table loaded with empty beer glasses in one of the town pubs. It might be ten o’clock in the morning, or midnight, with the landlord waiting patiently to lock up. They had lost all sense of time.

Attempts by their fellow professors to get information out of them, were met with resolute silence. They oscillated between moods of elation and depression, depending on how the project was going. So unpredictable was their reception of their colleagues that they were finally left alone. College life moved about them, as water about a rock set in a stream.

The month of October was nearing its end. The weather had been fine. Some of the tourists were still seen in shirtsleeves or light summer dresses. The bright, warm days followed each other calmly. Each morning, faces were turned to the sky and scanned the horizon for any sign of the weather breaking. Only a slight chill in the air at dawn and after sunset betrayed the lateness of the year.

THE TEST

At the time the machine was ready for testing, restoration work was going on in one of the college refectories. Layers of grime were being cleaned off the wood panelling on the walls. At night, the workmen went home. The huge hall was deserted. Old dust and new mingled in the smell of turpentine and varnish. The portraits of the past heads of college were all put in storage, and the pale patches left behind on the oak panelling began to look darker than the cleaned areas.

This was the place where the two men chose to set up their equipment. No-one would disturb them after ten o’clock at night when the college gates were locked. There was a good power supply from the cleaners’ equipment. The old wiring of the hall, dating back nearly fifty years, could never supply the current required.

Most of their equipment was unboxed, a mass of trailing wires and exposed circuitry. Several pieces refused to function when they were turned on. Patiently, Paul worked away, replacing, reconnecting, and sometimes even thumping, until there was a uniform glow of indicator lights and a quiet hum from each of the linked parts. The machine formed a circle of ‘nodes’, each joined to the next by heavy, black cable. From the top of each node projected two thin, parallel, glass rods, rising up more than two metres into the air. At the top of each rod was a complex prism of glass from which flashes of light, reflected from the workmen’s lamps, shot out in narrow beams. Although the prisms were stationary, the direction of the reflected light beams changed suddenly and randomly.

Professor Ketley dismissed the first idea that came to his mind, of the refectory looking like a ‘high tech.’ disco. No, the play of light was altogether more subtle, more purposeful. George had no idea what was going on in the network of machinery. He watched Paul’s face carefully to see if he could detect any sign of elation or disappointment.

“Is it working, Paul?”

“It’s just warming up. I haven’t activated all the fields yet. I think we must try to introduce them a little at a time, and see what happens. I don’t want to set it all in resonance at once, until we have the full-scale layout of the nodes at Sarah’s place. My resonance calculations are all to those dimensions. The ring here is less than a hundredth of the final size. We must be careful. It wouldn’t be difficult to do several hundred thousand pounds’ worth of damage to this little lot!”

“‘We are tampering with forces …’”

“George, we are tampering…etc. etc… that no-one understands!”

THE EDGE

Ketley noticed it first. Paul was busy watching the behaviour of his precious machine. There was no spectacular change in the equipment. The glass rods didn’t glow. There were no pyrotechnics. Somehow, this was more disturbing. He knew that most of the fields which the machine was generating worked even below the lower threshold of particle physics.

He felt a prickling on the skin of his face, like a million gentle flakes of snow brushing past all at once. He heard a low sound. It took a moment to realise that it was Paul calling his name repeatedly.

“Yes…yes, what is it?”

“George, move a little to your left. I think you are making that node opposite you oscillate. It’s unstable. Can you move?”

Ketley stepped away as he was told. The prickling sensation stopped.

Suddenly, the space within the circle of nodes seemed to come unhinged. Ketley glanced at the beams of light. His heart missed a beat.

In places, the beams from the prisms appeared to stop dead, and then continue from another place at a completely different angle. In other places, the beams seemed to duplicate, as if the space had suddenly become two layers of reality. Quickly, and with surprising self-possession, Ketley put a finger to the side of one of his eyes and pushed gently. The image wavered and overlapped. What he was seeing was definitely happening outside his head. It was not an act of imagination. The simple rules of stereo optics still applied.

Paul froze, half bent forward. The numbers on the display of the main controller’s sequencer changed and flashed at a furious pace. But that was not what worried the engineer. His whole body throbbed, it ached, with the sense of a presence in the ancient room. It was not even a uniform presence. It was legion. There was a feeling of untold essences filling and churning in the space. Nothing was visible. It was all instinct and intuition. The experienced and practical man felt a ball of blackness grow within him. It was not a void. It was the very essence of blackness, starting from the small ball and threatening to fill him, posses him. He was paralysed, bent forward. The numbers on the display were slowing. He felt a fear, a growing terror, that they might stop altogether. But he couldn’t move. He was on an edge from which there was no return.

A hand pushed the main power switch. The room cascaded into darkness.

The sounds of the streets in the town came faintly through the high, arched windows, distant reminders of the normal world.

Slowly, the eyes of the two men became adjusted to the dimness.

Professor Ketley’s hand still rested on the switch.

“What have we made, Paul? What have we made?”

THE INSTALLATION

“Where is Sarah. She said she would be here!”

The two men waited outside the house, which stood at the end of a lane, between fields and a wood.

George was annoyed. The change in the weather had set everyone on edge. The clear skies of the past weeks had given way to a poisonous and threatening dullness. The sky above their heads was a depressing, brown colour. The calmness and warmth through the month of October had been bought at a price. There was an aching tension in the air. Something was about to happen. The air was charged and close.

“For God’s sake, Paul, what are you doing?”

His friend was busy turning over the corners of the doormat outside Sarah’s front door. Sudden flurries of wind tousled his hair. He bent to look under discarded flower pots, and stretched to run his fingers along the ledge over the front door. George knew he was looking for a key. Paul’s calm and thorough hunt made George feel like an intruder.

“Does Sarah have a burglar alarm? Can you remember seeing one? George?”

George tried to picture the walls of the hallway in his mind.

“I can’t remember any alarm boxes. I never saw Sarah use a key inside the house. But, we…”

With the calm detachment of a thoroughly practical man, Paul took the hat off George’s head, placed it up against a small window pane beside the door, and punched out the glass. He reached in and unlocked the door.

His friend watched, open mouthed.

“We haven’t much time, George. Tonight’s the night!”

The phone started ringing in the hallway. The two men stepped inside and carefully wiped their feet. The answering-machine took the call automatically. A woman’s voice buzzed from the tiny speaker, “… Paul, I hope you’ve had the good sense to find a way in, and that you aren’t still standing outside waiting for me like a pair of lemons. I’m afraid I’ve been delayed for a little while. I’ll be with you as soon as possible, but do please set everything up without me, just in case I’m hours late.

“Switch off anything you like in the house to make sure you have enough power for the machine. There’s food in the fridge, and everything else is where you’d expect it to be. Don’t worry about walking mud into the house. Let’s make this work!…..”

The machine fell silent with a hollow click.

“I’ll start bringing the boxes in, shall I?”

“No, George. We’ll leave them in the van for now. I’ll set up the main controller in the shelter of that fence there. That way, our circle of nodes will enclose the house, part of those two fields, and the section of wood right down to the road, including the bridge over the stream,. It’s lucky that there’s a bridge there, otherwise I’d have to run cables over the road. We’ll have about a kilometre of cable running between the nodes, and we’ll enclose almost eighty thousand square metres of land. That should be enough, hopefully. Come on, let’s get it all set up and tested before the light goes!”

It was hard work. After an hour or two of strenuous labour, running out cables and carrying the boxes that contained the equipment for the ‘nodes’ from the van, both men were beginning to wish that they had recruited a couple of strong students to help with the lifting. It was too late now. They had to work on alone.

They sweated and swore, slipping on the leaves in the wood, tripping over tree roots, catching their clothes on barbed-wire fences, and filling their shoes with muddy water as they ran the heavy cables under the bridge. The van emptied. The circle was nearly complete. They arrived back at the house, but there was still no sign of Sarah.

“George, be an angel, and make us a sandwich and a cup of tea while I set up the sequencer, will you?”

“Paul, given the nature of the project, can you really see me as an ‘Angel’? However,” he added with a broad smile, “your wish is my command!”

READY

Paul had taken his power supply straight from the main switchboard in the house. Theoretically, the power should be adequate, but he was a little worried that there might be sudden fluctuations in the current taken by the equipment.

Sarah’s house stood alone in the countryside. Not many cars passed on the lane crossing the river. The equipment would be safe from interference by humans, but, if a large animal, like a deer, wandered too close to one of the ‘nodes’, it might make the whole system unstable. There was nothing they could do about that. It was a risk they would have to take.

Paul was pleased with himself. The links between the nodes were working perfectly. It was a tribute to his engineering ability. He set a small signal running through the ring, just to keep the electronics warm and dry. The device was far below the level of resonance. That would come later. The displays flickered. The numbers stabilised.

Paul unwound the cable from the sequencer’s remote-control unit back towards the house. The little black box worked all the functions of the machine. The sequencer would be drier and safer in the house, but Paul had decided that if anything went wrong with the experiment, he did not want to be anywhere near the sequencer. He had no illusions about the power of their machine. Sarah and George were relying on him for their safety, whether they realised it or not.

The sky was unnaturally dark for the time of evening. Clouds came to hang over the earth. Sudden, sharp winds twisted the branches of the trees. The earth waited.

It was the night of Halloween.

THE NIGHT OF THE SPIRITS

Father John sat at his desk and gazed out over the skyline of the old university town. He was a deeply troubled man. What was worse, was that he didn’t have any clear idea why he should feel this way. There was nothing unusual about the Mass he had conducted an hour earlier. The few people who bothered to attend had hurried away afterwards, frightened of being caught in a downpour from the threatening clouds that filled the sky.

No, his fears were not out there in the city. They were here inside him. He felt vaguely guilty. Weeks ago, with George, his old friend from his student days, he had felt too embarrassed to speak his mind directly. He regretted only giving that stupid ‘parable’ – Father John blushed at the thought – about Beethoven. What he wished he had said, was that he thought that the trio of university professors were playing a very dangerous game. The damage they could do could be permanent and devastating – he believed.

What could he do in these modern times, when belief had no real authority. Even in the Catholic Church, John’s views were seen as being a little irrelevant and old fashioned.

The priest fingered the beads of his rosary. His mind wandered. Purgatory: a place without God. John had often thought that this must be worse that Hell itself. He didn’t know if there was any real truth in the idea that those poor souls roamed the earth on the night of All Hallows. What he did know, was that the image of tormented beings, flying desperate and hopeless about the land, tortured forever by the nearness of life, was the saddest lesson to the living he could imagine. Yes, Hell was better – more definite.

Somewhere, deep inside him, John believed that sooner or later, he would know Purgatory. The formulas and rituals of his Catholic religion could not release him from the hopelessness of his hidden and terrible sin – the sin of the flesh, the forbidden love.

There was a knock on his door. It was Sarah.

THE HOUSE

The phone rang again. George picked it up.

“Hello, George?”

“Sarah?”

“Yes it’s me. Look … I’ve had to visit someone. I won’t be long, perhaps an hour and a half. I’m very sorry. Did you manage to get everything set up?”

“Yes, we did, but I’m still picking pieces of glass out of my hat…”

“What?”

“Never mind. Everything’s ready.”

“Great! Thanks. Can I speak to Paul, please?”

“Sure. Here he is……. Paul, it’s Sarah for you.”

“Hello Sarah. When does the wanderer return?”

“Paul, I’m really sorry. I know I’m late, and that I’ve left you both to do all the hard work. I’ll make it up to you somehow. Listen, Paul, I don’t know why, but I have an intuition that the machine should be started at sunset. Can you do that? I’ll be back as soon as possible. All the video, sound, temperature and pressure recorders are in the cupboard under the stairs. I think the whole lot will fit on the kitchen table. In fact, the kitchen is the exact centre of the ring, that is, if you’ve managed to get the ‘nodes’ set up in the positions we marked.”

“OK, leave that all to me, Sarah, but hurry back. As soon as the machine is started up, I’ll have to concentrate on keeping the circle stable – you know what George is like with anything technical. We need you back here to look after the sensors.”

“Yes, the ‘Professor of Probability’ will almost certainly wreck anything he touches. He’s just not a practical sort of man!”

“I’m listening to you two, you know,” said Professor Ketley.

They laughed. Paul put the phone down, and turned to his friend.

“Sunset. We start at sunset. These are good sandwiches, George, and there’s a lot of them!”

“It could be a long night. There’s also plenty of strong coffee on the stove to keep us awake. By the way, where is Sarah?”

“She didn’t say. Perhaps she has a secret lover. Perhaps she’s confessing all her sins. She takes her responsibilities very seriously!”

“Fine woman,” said George, wistfully.

SUNSET

The dark clouds seemed to meet as one with the ploughed fields in the distance. Paul looked at his watch. Suddenly, he felt a gentle glow of warmth on his skin. The sun cut a horizontal slash on the horizon, rich and yellow. Bright rays lit up the underside of the clouds. It was like a scene from a Renaissance painting, forming a perfect backdrop for the start of their strange and disturbing experiment.

The bright bar of light began to shrink as the sun sank lower. Both men stood outside the kitchen on the west-facing side of the house. Paul held the remote-control unit in his hand. At the moment the bar of sunlight shrank to nothing, leaving only a reddish glow behind, the engineer set the machine running. The lights in the house dimmed momentarily as the power surged through the cables between the nodes, and the nodes themselves started to hum with life.

It had begun.

WAITING

Nothing happened. The two men stood in the growing darkness, like children before a firework which refused to go off. Neither wanted to be the first to move.

“Do you feel it, Paul?”

“What?”

“It’s difficult to say. I feel as if all the ‘dust’ in my mind was being cleared away. I feel somehow more concentrated, more alert.”

“If you say so, George. Perhaps the charge we have put into the space within the circle has ionised the air here at the centre. That would certainly make you feel more awake.”

“Do you think it will work?”

“I hope to God that it doesn’t! There’s nothing more disturbing to a Agnostic, than the idea that there might be an ‘afterlife’.

“What do you think happens to people when they die?”

Paul looked out into the darkness of the night. He had not thought about these things for a long time. He smiled at his friend.

“Nothing is lost. And nothing has any meaning.”

“Nothing has meaning?”

“No meaning. Only value!”

Professor Ketley thought about this answer. He thought about the machine, and about what it was designed to do. He thought about the world that this night’s work might change forever. A sudden sadness filled him, clear and bright, and complete.

WITH THE PRIEST

“You’re angry, John. Why?”

Father John leant back in his chair, and stared at the telephone on his desk.

“For an intelligent woman, Sarah, you can be very unperceptive.”

He looked up, and saw the pain in Sarah’s eyes. The patience which his profession had taught him, was dangerously near its end.

“Why are you here, Sarah?”

“I felt I had to come. I wanted to see you before … before tonight; before the experiment.”

“Are you looking for an official referee from the Catholic Church?” asked the priest, a little sarcastically.

“John, please don’t be like that.”

“You don’t understand what you’re doing, do you? You have no idea of what is resting on this experiment of yours?”

Sarah’s heart ached. She couldn’t bear it. The love she felt for this man consumed her. It filled and blinded her.

“Sarah, priests study psychology. I am fully aware that the reasons people give for their actions, and their real motives are often worlds apart. Can’t you trust me in this?”

Sarah said nothing.

Father John looked into her eyes. He couldn’t hide what he felt – not from Sarah. He certainly couldn’t hide it from himself. No words of love were ever exchanged, no physical tenderness was ever shown, but they both knew. The priest feared for his soul, or rather, he felt that he might be lost already. He was helpless and resigned.

But, there was more depending on the experiment than the welfare of one man.

“Why, Sarah, why? Why must you do this? Please tell me how it can possibly be worth the risk?”

“Risk?” Sarah looked round the room. She examined the rows of religious books. She glanced at the crucifix on the wall. Finally, she turned back to face the priest.

“John, I must know! I must find out if the soul survives. The thing I want most in life – the thing I’ve wanted for most of my life – is out of my reach. I feel cheated. Perhaps in the next life …”

John listened to his breath going in and out. His mouth hung open. He felt the pricking behind his eyes, but he would not give in to the emotions raging within him.

“Love is a terrible thing, Sarah. The love of God is the only safe love. The love of man is capable of destroying everything.”

“But …”

The priest continued. His heart was open. He must speak.

“With certain and exact knowledge, there is no faith.

“Without faith, there is no salvation.

“Think, Sarah. If you prove the existence of an afterlife by science and measurement, where is the virtue in believing in God and following God’s commands?”

Sarah saw the tears of anguish in the man’s eyes.

“Sarah, your work tonight can strip the world of belief. You can destroy my life. You can make meaningless the lives of millions!”

PARTING

There was no sound in the room apart from the insistent, metallic ‘click, click, click’ of the priest’s cheap wrist-watch. The room was filled with pain and longing.

John slipped in and out of small prayers. He was powerless. All that remained to him, was the endless burden he had chosen to take on with his vows as a priest.

All he had was trust. His whole life was based on trust. He could not stop now. He must trust in God’s infinite mercy.

With a great effort, he managed to smile at the woman who stood clasping her hands a few feet away from him. He held up his palms.

“Peace!” He had become lighter, more businesslike. “Perhaps I’m attaching too much importance to the work of three ‘mad scientists’. The Church has survived for nearly two thousand years. Why not another thousand?”

John, I must tell you …”

“No, no, no,” interrupted the priest, standing up, “Tell me later. There will be plenty of time later on.”

Sarah allowed herself to be led out through the church. Someone was at work repairing the organ. A single note sang out in the space, sounding, at the same time, both melancholy, and patiently hopeful.

“John.”

“Sarah?”

“Goodbye.”

“God be with you too, Sarah, whatever happens.”

THE STORM

The threat was carried out. The storm broke. The sudden gusts of wind became more frequent, until they formed one continuous blast, wrenching at the trees, spinning leaves into the air, and upsetting the neat order of the garden.

George and Paul sat on chairs beside the laden kitchen table. They saw the tops of their heads reflected in the window panes, and beyond the glass, the turmoil and chaos of nature gone mad.

“Do you think the ‘nodes’ will stand up to this beating, Paul?”

“Well, if a tree doesn’t fall on one of them, the tripods should hold steady. The legs go at least two feet into the ground. The cones at the end of each leg will stop them being pulled out easily. Even if one of the nodes fails completely, there is a good chance that the circle of energy will hold. Whatever we had in the ‘net’ when we turned the system on, should still be inside. Whatever enters later will be held too,” he added.

“And?”

“As I said, whatever is inside will be driven towards the centre, eventually.”

“Eventually?”

“George, you weren’t paying attention when I told you all this, weeks ago! I’ll repeat: The nodes are generating electric fields at different times, and at different frequencies. It’s not the fields themselves which are important. It’s the relationship and timing between them which will drive Sarah’s ‘ghosts’ inward. The choice of time and frequency for each node is generated by the sequencer. It works – as you know – with some rather elegant probability calculations that you provided yourself. Remember?”

“You said, ‘eventually’?”

“Oh, yes. The energy structure of a non-physical entity, or even a dispersed physical entity will only coincide with the repelling force from the circle of nodes for a brief….”

“Paul?”

“What?”

“Thanks!”

“Anytime!”

SARAH ARRIVES

“Hello, you two. Thank heavens the rain has held off. It’s a wild night out there; trees down; tiles stripped from roofs. I’ve never been so glad to get home. How is everything going? I smell coffee!”

Both men noticed the flushed cheeks and the subtle lines of strain around the woman’s eyes. Both wondered where on earth she had been for the afternoon, especially since it was really her project.

“Anything to report?” she asked.

“Not a sausage! George thinks his ‘mental catarrh’ is better, but I wonder if it’s because he never stopped using those illegal stimulants from his student days!”

“Paul, please!” exclaimed George in mock indignation, “I’m a respectable college professor now!”

Paul smiled. “The words, ‘respectable’ and ‘college professor’ go together less often than most people think, my serious friend. Sarah, have a sandwich. Have a coffee.”

“I’m too excited. I’ll wait until later. What a filthy night! You could believe anything on a night like this.”

WAITING

“Are you sure that nothing has happened?” asked Sarah, after a long hour of waiting had passed uneventfully.

Paul looked at his notes. “Nothing. There was a power drop a while back, but that was probably an overhead cable damaged by the wind, and the power station having to re-route the supply. These things happen in weather like this.”

Professor Ketley stretched back in his chair, and looked in turn at each of his companions.

“Sarah, Paul, something occurred to me when I set up my original equations.”

“What was that?” said the pair in unison.

“I had to make a certain assumption right at the beginning. I won’t bore you with the mathematics, but the design of the field generator means that the forces are concentrated in a flattened ‘bubble’ of energy lying on the earth. The field reduces quite sharply above the upper level of the nodes, and it doesn’t go below ground level at all.

“I know the assumption that Sarah made, was that, if the souls of the dead do return, there will be a large number of them. This may be true, but if these ‘souls’ travel higher up in the air, or even below ground, we’re not going to ‘catch’ one. I’m sorry, Sarah. I know this experiment is very important to you, but for me, the whole project has been the challenge to create a sustainable field of this nature. The least I get out of the work we have done, is a substantial research paper. The same is true for Paul. Yes? No?”

Reluctantly, Paul nodded his head.

Sarah breathed a deep sigh. Why was everything so tied up with practicalities? She wanted answers. She didn’t want more problems. Why was her life so difficult, so hopeless? Why was the man she loved most in all the world, and had loved since her time at college studying for her first degree, unobtainable?

She swore under her breath, but the words offered no relief. Finally, she grinned at her two friends, and shrugged her shoulders.

“The night is young. Will you stay and see the experiment completed, even if we get nothing for our trouble? And…”

Sarah’s request was interrupted by a furious hammering. Their hearts skipped a beat. They turned and looked through the kitchen doorway, down the hall towards the front door. Even from that distance, they could see it shaking under the pounding. Sarah was the first to react.

THE MOTORIST

“Paul, you stay here and look after your machine. George and I will answer the door. The hammering continued without a break. The door rattled under the force of the blows. George felt his stomach lock in fear. Sarah went ahead and opened the door. It flew back with a violent scrabbling of desperate hands.

The man almost fell into Sarah’s arms. He was covered in mud, panting, red faced, eyes wild. Blood trickled steadily from a line of cuts across the side of his face. George felt an instinct to attack the madman and free Sarah from his clutches. Sarah saw it differently. She helped the man into the hallway, and pushed the door shut with her foot.

“You’re all right now. You’re safe. Sit down here. George, get come brandy. Bring the first-aid box from under the sink in the kitchen. Come on!”

Professor Ketley obeyed without thinking, pleased that someone was taking responsibility. The man was hoarsely gasping the same word over and over again. Finally, he understood what the man was trying to say: ‘telephone!’.

THE CAR

“You’re OK, you’re safe now. What’s happened?”

“The car! The car! The bridge! Down by the bridge! The crash! I saw the light here, through the trees. I ran as fast as I could. We must get help. Where’s the telephone? We must phone at once! Now!”

Sarah stopped bathing the cuts on the man’s face, and turned to pick up the telephone. She lifted the receiver and put it to her ear. There was no dialling tone. All she heard was a faint, crackling hum. She pushed down the button to close the circuit and released it. The same hum. She did this several times.

“Paul. Come here for a moment. Listen to this. Come here. It’s important. Tell me what’s wrong with the telephone. There’s been a crash. We must phone for help right away. Hurry up!”

Paul ran through from the kitchen carrying a small test-meter. He took the receiver from Sarah’s hand and listened, working the button up and down. He unplugged the telephone from its socket on the wall, and pushed the probes of his meter into the socket. After a few moments, he looked up at Sarah.

“It won’t work. The wires aren’t damaged, but the telephone-exchange won’t give us a line. I don’t know why.”

The man was calmer now. His breathing had steadied and lost its rasping quality. He took a deep breath and looked up at the three standing over him.

“We must get help. There’s been a terrible accident. I was driving back from work. I took this back road because I know how people drive on the main road in this awful weather. Everyone is in a mad rush to get home. I saw the rear lights of a car. Then I saw the tree down across the road – just by the bridge. I stopped, of course. I had to stop. The road was blocked. There must have been a crash. The car had driven into the tree, or the tree had fallen on the car. Terrible! We must get help!”

George put his hand on the man’s arm to get his attention.

“Someone is hurt? The person, the people in the car? Is someone hurt? Do you know how?”

“Of course! Because they hit the tree. They were hurt because they hit the tree!”

“No, no,” George persisted, “In what way are they hurt? Do you know how badly?”

The man looked up helplessly into Professor Ketley’s eyes.

“Too badly! I think … I’m sure they’re dead. Terrible! Twisted! Blood! We must … we must……”

“How many?”

“I’ve told you! There was only the driver. Terrible!”

“You’re sure that the driver is dead?”

“The eyes! The neck! White….white…”

The three experimenters moved away from the man and spoke together softly. Paul turned his back to the poor motorist and said hurriedly,

“One of us must go down to the bridge. George, if you are prepared to do it, we can give what help is necessary without having to turn off the machine. Do you understand? Sarah can look after this man. I can look after the equipment. We only need to run a few more hours.”

“It sounds a bit heartless,” said George after a moment’s thought, “But I suppose, if the driver is dead, we won’t help by wasting our night’s work – and all the weeks before. Don’t worry. I’ll go.”

“Thanks,” said Sarah, a little ashamed all the same.

George took a waterproof coat down from a hook by the door. It was a tight fit, but it was better than nothing against the scouring wind. There were no rubber boots his size. His wet shoes were cold on his feet. Sarah found a torch for him. Paul went into the kitchen and returned with a large battery lantern.

“It was for lighting up the nodes if anything went wrong in the dark,” he said, holding out the powerful torch. Professor Ketley took it, and went out through the front door, closing it behind him. The curtain beside the door flapped as the wind blew in through the broken window.

THE POWER OF THE MACHINE

“Sarah, bring him and the bottle through to the kitchen. It’s warm there. He’ll be all right.” Paul led the way.

“Poor woman,” muttered the motorist.

“What? Sorry. What did you say?”

“Poor woman. In the car: poor woman.”

Sarah felt a stab of sympathy for the driver, dying – if she was really dead – all alone on the wooded road.

“Perhaps it was quick. Perhaps she didn’t suffer too much.” The words sounded hackneyed and glib in her ears as she spoke. But she meant them, all the same. What more could we say about death. What words had not been used countless times before. They found their way onto thousands of different lips – always meant, never enough.

“Damn!” Paul swore quietly to himself.

“What is it, Paul?”

“I’m stupid. I should have realised. The phone. Of course, the phone. With all the energy we’re putting out, I’m surprised all we get is a hum, and not Mahler’s third symphony!”

“What are you saying?”

The motorist looked from one to the other. He did not seem to have noticed all the equipment piled on the table, the winking lights, the mass of cables running here and there in the comfortable country house.

“The machine! The energy fields are stopping the telephone from working properly. Sarah, I’m afraid we must turn off the device. We really must get help. Even if the woman is beyond help, we can’t leave her trapped all alone in that car for the whole night. It’s not right. Anyway, someone else may drive right into the back of her car. It’s not safe. We must turn the machine off! At once!”

THE MACHINE STOPS

Sarah stood back against the wall. She felt alone and confused. Her mind flew in every direction at once, looking for a way out.

But, underneath it all, she knew that Paul was right. It was selfish to continue the experiment if there was any chance that the phone might work again if the circle of nodes was switched off. George was not a trained medic. Even if the woman could be helped, he would not know what to do. He could only run back to the house, and the problem of the phone would still be there.

“I’m sorry, Sarah. Perhaps we can do this again next year.”

“Yes, Paul. Thank you. Turn the machine off.”

Paul paused for a moment, before reaching for the remote-control unit. The display glowed full of mysterious numbers. His finger hovered momentarily. He took a deep breath, and pushed the red button.

FADING

Sarah watched the screens and lights go blank. Immediately, as the life left the electric circuits, the room went from looking like a laboratory, back to being an ordinary kitchen, cluttered with strange bits and pieces of equipment. She felt a little faint.

“It must be the strain.”

The brightly lit room seemed to become less well defined. The edges of objects took on a vague halo, and were, somehow, insubstantial.

Sarah leaned back against the wall. The wall felt ‘soft’, as if her back was becoming numb.

“God,” she whispered to herself, “What a day! Still, it’s almost over.”

She experienced a little stab of surprise. Was she ill? The kitchen was now even hazier. She could not see along the hallway at all. Everything was hazier, dimmer. The light was going.

“What is happening?” She spoke out loud to the men sitting at the table. They did not seem to hear.

“It’s getting dark. What is happening to me? Paul. Help me. I can’t … I don’t … Call John. I want to speak to John.”

Sarah felt her mouth working, but no sound came out. The light was almost gone.

Sarah Goring faded from view, leaving the motorist and the scientist alone in the bright kitchen.

George looked at Sarah, sitting, dead, at the wheel of her car.

His tears fell on the corrupted and distorted metal panels, which were crushed beyond recognition by the great tree.

Professor Sarah Goring had the proof she wanted.

Either way, she had the proof.

P W Barnabas – October 31st 2012

Copyrighted – Ask Kill Your Pet Puppy for permission – Ask Kill Your Pet Puppy for permission – Ask Kill Your Pet Puppy for permission – Ask Kill Your Pet Puppy for permission

Artwork – Ferelli

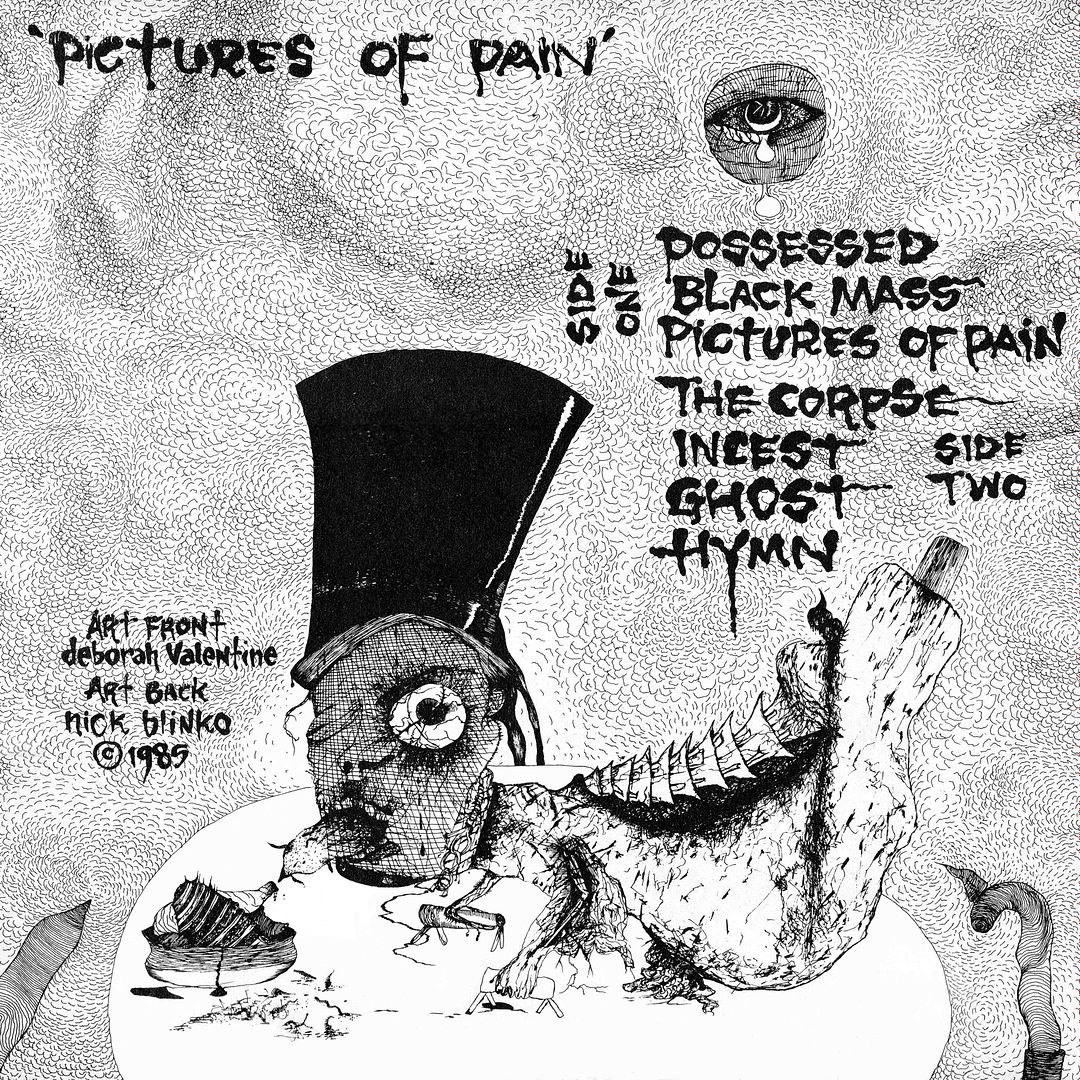

An officially sanctioned reissue of the classic and long deleted PART1 mini album ‘PICTURES OF PAIN’ will be released soon on the All The Madmen record label in a suitably dark and moody coloured vinyl pressing. The sleeve will be adorned with the original artwork by Deborah Valentine and Nick Blinko that has been stored safely in the dark vaults of Mark Ferelli since the original release.

This mini album will also include an eight page lyric booklet with unpublished artworks by Mark Ferelli.

The original copies of this mini album were released on the Pusmort record label in 1985.

This reissue on the All The Madmen record label will celebrate thirty years passed.

More details may be gained from these sources very shortly: