When Fate Deals It’s Mortal Blow / Burnout / The Spin

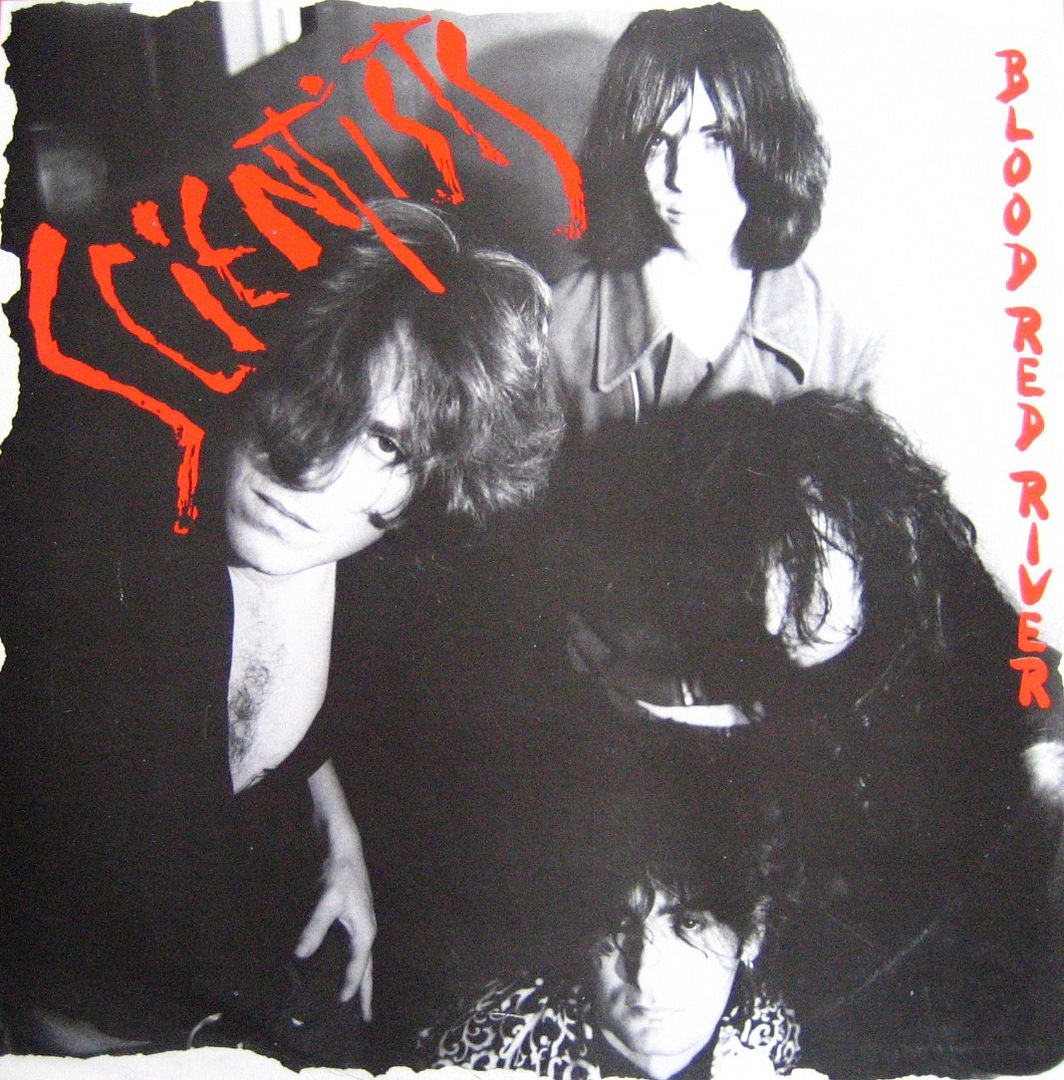

Rev Head / Set It On Fire / Blood Red River

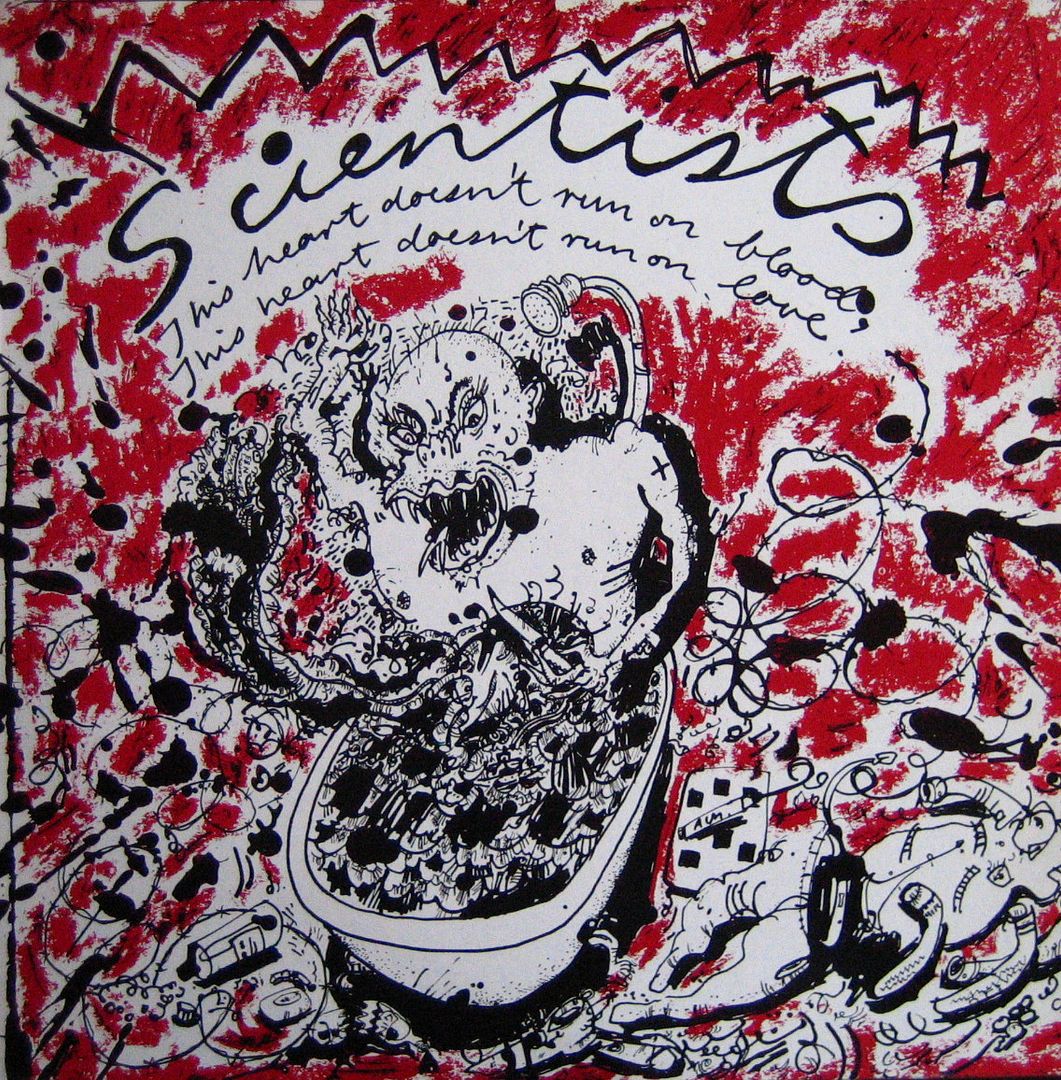

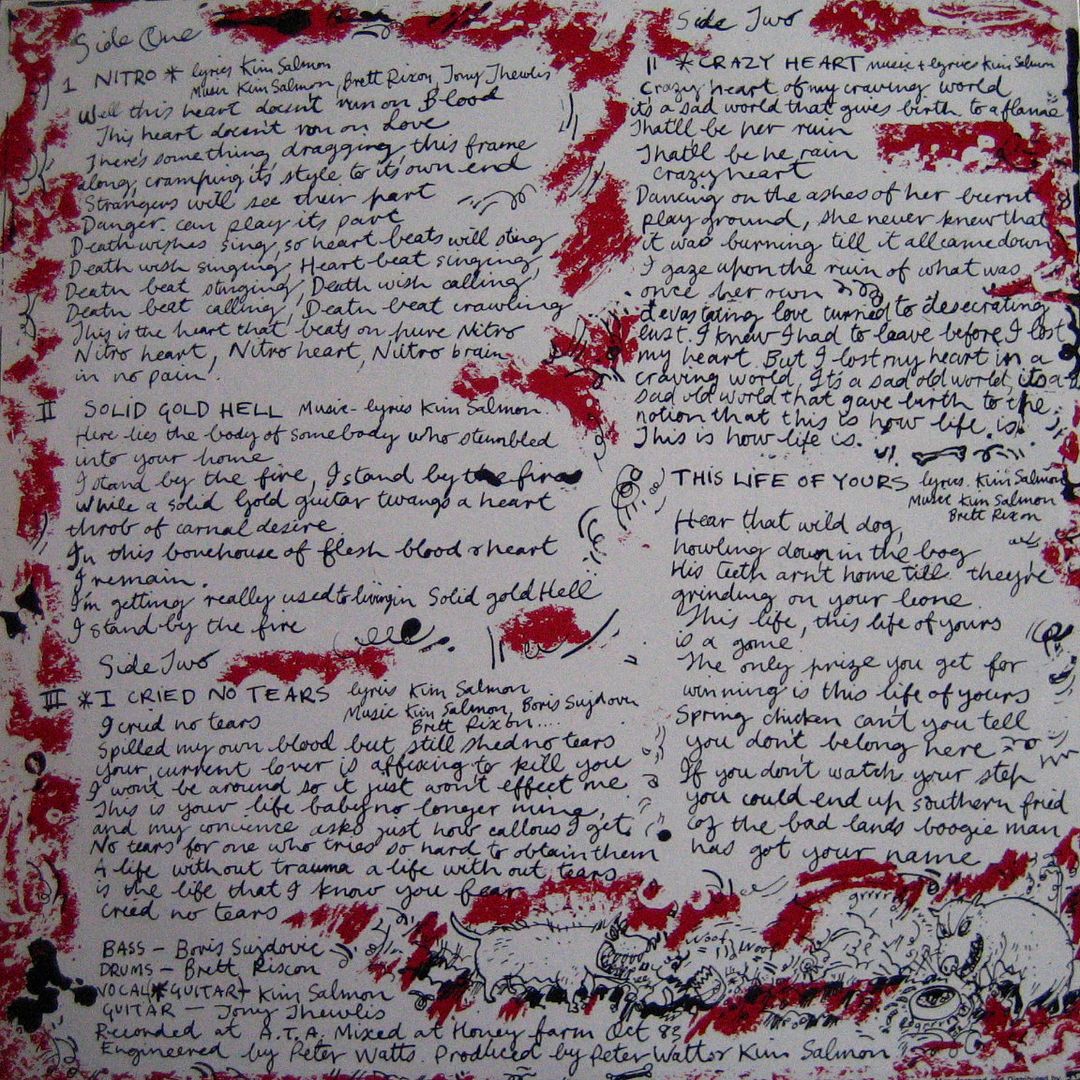

I Cried No Tears / Crazy Heart / This Life Of Yours

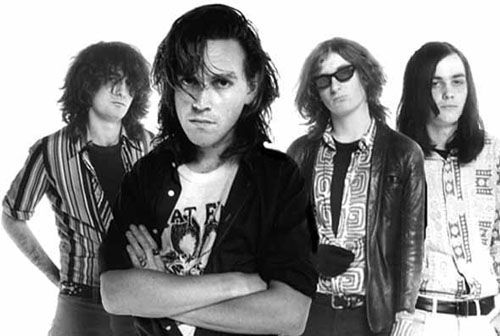

The Scientists performed a fair bit in London venues around the mid 1980’s. I was lucky enough to see the band a handful of times at various places; The Broadway underneath the Clarendon in Hammersmith, The Broadway’s big brother The Clarendon, Bay 63 in Ladbroke Grove and at Dingwalls in Camden. Maybe one or two more places that I can not recall right now. Always a great live act, the rhythm guitarist cutting up his fingers badly whilst thrashing the guitar strings so hard trying to ‘out Stooge’ Kim Salmon on the lead guitar, blood all over the pick ups of his lovely Fender Jaguar. The Scientists were that kind of band!

Uploaded today are the records that I first heard that got me into the band in the first place. The recording sessions for both these releases took place in 1983, although the 12″ EP ”This Heart Doesn’t Run On Blood’ came out in 1984.

Text below is a Kim Salmon interview by Patrick Emery for i94bar.com website and following that are some notes for this era of the Scientists from scientists.com.au website.

Kim Salmon claims to have a patchy memory of the recording of The Scientists’ debut mini-album, “Blood Red River”, which the band will play in its entirety as part of the Don’t Look Back concert series. Recorded in Melbourne’s Richmond Recorders in 1983, eighteen months after The Scientists had arrived in Sydney to pursue their musical prospects, Salmon describes the recording process for Blood Red River as “speed-addled and alcohol-ridden…midnight-to-day recording sessions”. But the passage of time hasn’t quelled Salmon’s pride in the album, or the period in the Scientists’ life that it represents. “There was very good chemistry in the band,” Salmon recalls. “It was formative, but also its defining days. It was the best period for us.”

Salmon had formed the first line-up of The Scientists in Perth in the latter part of the 1970s. The first line-up included James Baker, at the time recently of The Victims, and subsequently a founding member of Le Hoodoo Gurus, the Beasts of Bourbon and The Dubrovniks, together with a revolving door of notable musicians, including Roddy Radalj (Hoodoo Gurus, Dubrovniks, Surfing Caesars) and Boris Sudjovic.

The first incarnation of The Scientists bears only marginal resemblance to the swamp and grunge of the 1980s version, with the band’s repertoire more attuned to Baker’s attraction to the 60s garage tradition (see the Citadel CD re-release “Pissed on Another Planet” for a survey of the Baker-Salmon era Scientists). “The songs from the first line-up of The Scientists came from a songwriting partnership between James Baker and myself,” Salmon says. “We wrote what came naturally to us. But that style of music wasn’t exactly what I wanted to do when I was gripped by punk rock,” he says.

The apex of The Scientists Mark I’s tenure came arguably with its appearance on Australian pop music show Countdown where they played “Last Night”:.

The Scientists returned to Perth, where its prospects appeared limited. Salmon, for his part, was gravitating back to the dark, jagged and swamp shade of punk he’d initially been attracted to. “As the first line-up of the band peetered out I became interested in The Cramps, and renewed my interest in The Stooges,” Salmon says. Salmon hooked up with fellow Perth residents Kim Williams and Brett Rixon to form Louie Louie. “Louie Louie was the prototype for next version of The Scientists,” Salmon says. “’Swampland’ was written in that band.”

Around the same time Salmon bumped into former Scientists bass player Boris Sudjovic, who’d recently moved across to Sydney. Sudjovic was looking for a musical outlet, and suggested to Salmon that The Scientists were likely to find a more receptive audience on the eastern seaboard. His interest piqued by Sudjovic’s description of the Sydney music scene, Salmon set about rebuilding the Scientists. “I asked James Baker, but he was already in Le Hoodoo Gurus,” Salmon says, “and Kim Williams wanted to stay in Perth”. Louie Louie drummer Brett Rixon assumed drumming duties, while the second guitar spot was filled ultimately by Tony Thewlis, another Perth resident.

“I spoke to Tony, who’d wanted to join the previous pop version of The Scientists,” Salmon says. What Thewlis didn’t know immediately was that the band he was joining was a different creature to the band he’d wanted to join a few years before. But that didn’t stop Thewlis embarking on the long car trip to Sydney to seek the band’s musical fortunes. “All of us went to Sydney,” Salmon says. “I had this idea of what we were going to do. Brett knew what we were going to do because he’d been in Louie Louie. I think it was more that Boris had a problem with it,” Salmon laughs.

Sydney in 1981 was still in the grip of the Radio Birdman legacy. “When we first went to Sydney it was very much post Radio Birdman,” Salmon recalls. But The Scientists’ sharp deviation from the prevailing Motor City twin guitar style didn’t seem to hamper the band. “We were very aware of the Radio Birdman thing when we moved to Sydney,” Salmon says. “We didn’t want to continue with the tradition of paisley shirt and the Talk Talk retread riff,” he says. “We had our own agenda. I think for a lot of people in Sydney it didn’t occur that could do anything different”.

Salmon muses that The Scientists sound – later described as the progenitor of the ‘grunge’ style that swept through the independent music industry in the early 1990s – was the zeitgeist waiting to happen. “When we recorded and played ‘Swampland’ people loved it,” Salmon says, “so there was something going on”. Salmon says that the sound was striving to achieve was born of an interest in Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Cramps and The Gun Club (at that time arguably at the peak of their creative powers).

“A band like The Cramps has a definite schtick,” Salmon says. “With us – or with me – it was very much a case of looking for something that hadn’t been done”. Salmon suggests that part of the attraction of The Scientists was its multi-faceted character, or conversely, the difficulty of pigeonholing the band’s sound.

“People heard in it what they wanted to hear,” Salmon says. “Some people thought we were a psych band, some people thought we were a garage band, and other people thought we were none of those things,” he laughs. So were you looking to define the band’s sound, or to explore it? “That’s interesting,” Salmon replies. “It was a bit of both, I think,” he says. “To me I can hear things in that band all the time,” Salmon says. “I can hear Can in the band, and Krautrock,” he says. “And there’s a lot of jagged edges in that band as well”.

Withing a short period of moving to Sydney The Scientists were building a reputation for impressive live shows – despite the band’s lack of enthusiasm for sound checks.

“Dave Graney asked me the other day ‘So, are you going to do a sound check?’, because we didn’t sound check in those days. One time we came to Melbourne to play the Seaview Ballroom and we got straight out of the van and just started playing,” Salmon laughs. It was also in Melbourne that The Scientists met Bruce Milne and Greta Moon, at the time principals of the AuGoGo independent record label, which would go onto release “Blood Red River”.

“I’d seen Fast Forward [the independent music zine published by Milne, which came with a cassette compiling independent bands of the time] and thought it was a good idea,” Salmon says. “I gave Bruce a copy of our cassette we’d made, and I did an interview with him about what I thought rock’n’roll was all about. Later on he offered to put out our mini-LP,” he says.

Twenty-five years later “Blood Red River” withstands even the closest scrutiny. Rumbling beats, jagged guitars that hurl a spear through your musical senses, with Salmon’s peculiar guttural vocal chants describing vivid tales of confusion and angst that could have been procured from a Edgar Allen Poe short story. “Set It On Fire” – replete with Salmon’s hair raising screeching chorus – remains a certifiable classic, while the fatalism of “When Fate Deals Its Mortal Blow” is as harsh as any convict novel.

“Those songs were my first attempt at writing lyrics,” Salmon says. “It was life seen through the eyes of a 20-year-old living in Sydney. Someone described it once as ‘a filthy sub-world of hate and lust’,” Salmon laughs.

For all of the imagery in the songs – the title track itself is worthy of a post-graduate academic treatise – Salmon says there’s nothing much to the lyrics. “It wasn’t particularly apocalyptic, even though some people thought it was,” Salmon says. What about the song Blood Red River? “There was cowpunk around the time, and I think it was influenced by that,” Salmon says. “They’re just lines, they don’t mean anything”.

That said, some of the tunes – “Burnout” and “Revhead” especially – give a clue to the members’ backgrounds in Perth. “We were all from the suburbs of Perth,” Salmon says, “not from Caulfield Grammar”.

Salmon is keen to pay tribute to Chris Logan, the record’s producer, who achieved a ‘fat’ sound on the record later Scientists recordings were unable to replicate. “He was doing our sound at a gig, and he came up to us later and said ‘you guys are a wild bunch’. He was a pretty idiosyncratic chap – he looked disturbingly like Francis Rossi from Status Quo. He was very particular about what he did, and very dedicated to the craft of making sound – he was a slide rule sort of a guy,” Salmon says.

Listening to the record now, Salmon is still impressed at Logan’s production efforts. “It’s very fat, and it’s got a lot of bottom end,” Salmon says. “Thanks to his meticulous skill and those fantastic side burns he managed to get a great sound,” Salmon laughs.

And it wasn’t just Logan’s production skills that did the trick – Logan also claimed an empathy with The Scientists that turned out to be authentic. “Chris believed he knew what we were about, and he probably did,” Salmon says. “Chris deserves a lot of credit that he probably hasn’t ever received,” he says.

In 1984 The Scientists packed their bags and headed to Europe, joining the exodus of Australian bands including The Moodists, The Birthday Party and the Go-Betweens. “We eventually ended up leaving Sydney. Brett had had enough, and he was a bit frustrated, and he said ‘we’ve got to get out of here’,” Salmon says. “We ended up in London in 1984. It was a very difficult thing to do, but it was lucky in a lot of ways”. Despite the mythology of poverty, squats and tinned food that’s regularly promulgated by historians of the era – a mythology that fellow expats of the time like Mick Harvey still objects to – Salmon says The Scientists found almost immediate favour. “We ran into Ken West who gave us some names that we called up,” he says. The manager of New Order arranged for the band to go to Manchester (“he said ‘our bass player would like this’ “), and things quickly fell into place. “Straight away I found myself talking to a whole lot of enthusiastic journos,” Salmon says. That said, there were the occasional negative commentators.

“Some Perth journalist who was working for NME said we were copying the Birthday Party,” Salmon says, rolling his eyes. The notoriously fickle English music press had plenty to say about The Scientists, not always in tune with what the band was thinking itself. “The thing about NME was that later on when we’d lost the plot they said ‘they’ve lost that post-crucifixion blues thing’,” Salmon laughs.

Eventually the The Scientists’ European sojourn ran its course, as the band’s sound began to stray from its original course – the Human Jukebox period of the band is a precursor to where Salmon would pick up with his next outfit, the Surrealists – and the relationships within the band began to fray. “One day I got fed up with that angsty sort of thing,” Salmon says. “Then Brett left. The stuff afterwards was never as good,” he says.

The band had also been plagued with legal problems, after its relationship with AuGoGo went pear shaped. Salmon isn’t keen to discuss the legal dramas in detail, though it’s clear he learned a lot about music contracts (albeit the hard way) from the experience. Suffice to say, AuGoGo asserted its rights under the contract, and the band disputed those rights, and never the twain shall meet.

Salmon eventually returned to Australia, and embarked on a final Australian tour in 1987 before retiring the band for almost 20 years. Salmon formed the Surrealists shortly after the demise of The Scientists, before teaming up with ex-Scientists Boris Sudjovic and James Baker (and Tex Perkins and Spencer Jones) in the Beasts of Bourbon.

In 2000 Salmon put together a rotating band of musicians to promote the release of the “Blood Red River” CD release, followed by another series of shows in 2002 (this time featuring Tony Thewlis on guitar and Boris Sudjovic on bass). In 2004 Salmon formed a new line-up of the band featuring Stu Thomas (who’d played with Salmon in the Surrealists and the Business) and Leanne Chock (who’d joined The Scientists’ not long before its demise in the late 1980s), undertaking a short tour of Europe.

In 2006 The Scientists, this time with Sudjovic and Thewlis on board, were invited to play at the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival in England, which became the catalyst for the band’s appearance as part of the Australian leg of the Don’t Look Back festival. The Scientists will play “Blood Red River” in its entirety, together with a selection of tracks recorded around the same time, including “Happy Hour”, “Swampland”, “Fire Escape” and “We Had Love”.

As the interview winds to a close, Salmon reflects on the potency of The Scientists in its “defining” era. “I don’t think there’s even been a band that could play two notes as good as us,” he says. But Salmon is also quick to dismiss any suggestion The Scientists was a simplistic musical outfit. “I spent a lot of time dumbing it down and making it simple like The Ramones, when it really wasn’t,” Salmon says. “I invested a helluva lot in that band – there’s a lot of things going on in there that people hadn’t done,” he says.

Salmon’s reference to the Ramones leads me to muse self-indulgently on the paradoxical skill of rock’n’roll to continually explore the near-infinite artistic reaches of three chord riffs – a contrast, I suggest, to the multi-dimensional orchestral layering of Mozart. Salmon’s response is swift.

“The Scientists are like Mozart!” he says, without a hint of sarcasm.

PATRICK EMERY

1. (SUB)URBAN MYTHS

So much has passed since the sounds on this LP were first generated that it feels as though they were created by a different set of people. But it is in fact Boris, Tony, Brett and I who are guilty. It was indeed us who travelled some 2000 kilometres across Australia to form a band never having played together before; who decided to grow our hair long to be different from everyone else in the early eighties; who got bottled off stage by a disgruntled crowd of 1000 at the Parramatta Leagues Club after 15 minutes of supporting pub rock stalwarts, The Angels; who, prompted by a good review from Barney Hoskins in the NME, left behind a promising future as Australian ‘pub rock’ icons ourselves to languish in relative obscurity in the UK; who got booked into a whole pile of European festivals by a long haired chap called Willhelm in a Dutch agency called Mojo because he took one look at our photos and thought, “these Scientists [with their long hair] are kindred spirits”; who had fewer rehearsals than the number of songs in our repertoire over our entire history; who did a couple of European tours by rail, getting the clubs to provide backline; who would methodically all walk off in four different directions on arrival at each foreign station to have Leanne, our tour manager, round us up; who hated the idea of playing to an audience that was more inebriated than us; who believed that we were the greatest rock and roll band in the world with absolute conviction and no irony.

2. THE BOYS

It was Tony Thewlis who I spied one night playing some absolutely superb guitar with some absolutely godawful band at Hernando’s Hideaway in East Perth. He thought The Scientists I was offering him a place in was the earlier brash ‘pop’ group he saw on national pop TV show ‘Countdown’. He moved to Sydney to join up but when it dawned on him it was something else entirely, he began extracting all manner of dissonant, jarring, downright rude sounds from his guitar, probably to piss everyone off as much as anything else. Tony found his entry into the maelstrom one day listening to Like Flies On Sherbet by Alex Chilton. After that…..try and get him to not be spontaneous! He would refuse to play anything vaguely approaching a rock solo. He would be twice as inebriated as the rest of the band – he didn’t drink beer so matched our beers glass for glass with cider or wine. He was quite a sight with his Johnny Thunders-style teased hair throwing his guitar at the floor, the ceiling, his amp or even audience members (this stopped when Boris’ girlfriend, Pip, ran out to retrieve it from a thieving punter) all whilst wearing a fur coat on inside out.

Drummer, Brett Rixon, brother of two years running Penthouse Pet of the Year, Cheryl, had on his wrist, a self-inflicted tattoo of a safety pin with two lines representing the bridge of skin the prong passed under. He was described by one Robin Gibson of Sounds magazine as having “the demeanour of an assembly line misfit blankly contemplating murder”. He did have a dark sense of humour. For example, there is a tape in existence of him in a ‘discussion’ with Boris on the relative personality merits of two chaps they knew, one of whom had attempted suicide by hanging. Brett’s argument against the other chap was that, “If you were to find him dangling you’d give his leg a tug”. But Brett had an understanding of the brief. It was with me and a fellow called Kim Williams back in Perth in a band called Louie Louie that we first successfully got onto the ‘primitive’ tangent – Swampland was originally a Louie Louie song and a co-write with Mr Williams.

Boris Sujdovic liked to act dumb to be left alone but was actually a smooth talker when it suited him. Importantly, his laidback disposition made it very easy for him to adapt to the idea of two note bass lines. In fact, he was the one that started all this by persuading me to reform The Scientists in Sydney with him on bass. He was the tallest and meanest looking of us but was actually the one most likely to make a friend at the bar. He was also the member most likely to have a joke at the expense of the others. Band members often acquire nicknames amongst themselves. Boris’ was ‘Ogre’. (My nickname was Wilf. Obviously I didn’t pick it. The protocol with nicknames is that you don’t get to pick them or change them if you dislike them. I acquired mine through a trick of the light giving me a ‘codgerish’ appearance in one photo. I think I said something to the effect of, “Fuck, they’ve made me look like Wilfred Bramble [of Steptoe and Son]”. It was either Brett or Boris who could not resist it and that was the end of it. From then on it was Wilf this or Wilfy that.)

I believed these guys were the perfect raw materials to work with (or just leave alone as the case may be). I thought I had it sussed. All they had to do was go on being themselves and let me point them in the right direction, that is, compose the right kind of material.

3. THE MANIFESTO

First off, we did not want to align ourselves with anyone. We wanted to be left alone to do what we wanted without the encumbrances of so-called ‘artiness’, rock and roll traditionalism, ‘pure perfect pop’ craftsmanship or anything else that might stand in the way of our intentions. These were not to bury rock ‘n’ roll but to strip it back and rebuild it to our specifications (a bit like a ‘hotted up’ car). We loved rock ‘n’ roll’s tradition but despised traditionalism, hated artiness but naively believed what we were doing was art (when it worked). We believed we were on a mission to take rock back to its most basic primal essence. Only then could we add our own flavours which would be spontaneously concocted out of Companion fuzz boxes, beer, various chemicals, anarchy and whatever else was handy at the time. At times it would be beautifully simple, at others quite tricky getting it right. Real rock ‘n’ roll was dumb and sophisticated, serious and funny. A paradox. You couldn’t hide behind a joke. You had to be prepared to go out and be a joke. The path of riotousness was the path of righteousness and only we were on it. We didn’t just believe, we knew that we would be misunderstood first, worshipped and adored later. Clinton Walker, author of Stranded – The Secret History Of Australian Rock And Roll was the perfect example. At first he didn’t get us and thought we were ‘daggy’ but then later went on to sing our praises, over and over, for magazines such as RAM and Rolling Stone. We did not want to change the world. It could sod itself. We wanted only to be left alone… and admired from a distance.

4. PERTH

We left Perth behind. It had rejected The Scientists’ first incarnation so the reincarnated Scientists rejected Perth without giving it a second chance.

5. SYDNEY

In 1981 Sydney’s inner most suburbs of Darlinghurst and Surry Hills were home to a rock scene whose mecca was Detroit, home of The Stooges and MC5, even though Surry Hills and Darlinghurst were as far away from blue collar Detroit spiritually as they were geographically. But of course no-one knew that or even cared. Radio Birdman was every Sydney ‘underground’ band’s mentor. This ‘Sydney’ legacy didn’t mean much to westerners like us. We simply didn’t buy it. Inner city Sydney was, however, a tantalisingly wicked place for a bunch of Perth suburban boys who got taken in very quickly and nurtured down an inebriated path from their home in Nickson Street, Surry Hills to the Southern Cross Hotel, to the Sydney Trade Union Club and out into the oblivion of Sydney’s pink bat-ridden night.

Early in 1982 we got a Friday night residency in neighbouring suburb Ultimo’s Vulcan Hotel. We were still working on our sound and image but Tony could always be relied upon to ‘chuck a wobbly’ and Brett and Boris were presenting a very granite-faced deadbeat hair in the eyes demeanour as we thrashed our way through a set that each week had fewer chords and more noise. Although we replaced the mandatory ‘Detroit’ buzzsaw guitar three chords with atonal guitarscapes and two note bass lines our shtick was too ‘dumb’ to be art rock. Thanks to a supposed but actually non-existent allegiance and some wild shows it wasn’t long before the Vulcan was packed with paisley-shirted and mini-skirted regulars singing along to Swampland.

6. MELBOURNE

Occasionally we would go down to ‘arty farty’ Melbourne which in the absence of its beloved Birthday Party lapped up a sound as loud and as ugly as ours. For instance, I remember doing a show opening for a bunch of brass playing ‘penguins’ called the Hot Half Hour at the Seaview Ballroom in 1982 before we even had a record out. Greg Perano, fresh out of Hunters and Collectors, had some clown with him who was heckling us and our hair. The jibes quickly changed to cheering once we began making a noise.

7. ‘OZ’

Releasing Swampland as a single ensured our reputation spread to Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane. Then when a video for Blood Red River seemed to be followed by a demand for us outside the sacred sanctum of Sydney’s inner city we found ourselves playing more and more frequently in the beach suburbs to the “deadset mate” and “filth” brigade. In a complete turnaround, agencies that gave us the bums rush when we first graced them with our presence were trying to get us onto their books. Dirty Pool offered us a tour supporting The Angels which culminated in the infamous Parramatta Leagues Club bottling incident. Sydney’s 2JJ were very supportive and gave us a Live at the Wireless slot from which we derived We Had Love, probably our finest recorded moment to that point. We Had Love even charted briefly on AM radio somewhere in Sydney!

It seemed to me at the time that suburban pub rock Australia was indeed promising itself to us. But before it could be had we were in London leaving the way open for The Celibate Rifles, Died Pretty, Painters and Dockers, and a plethora of post-punk rock bands to fill a new demand for ‘underground’ hard rock.

Some images that I have from those Sydney times are: Brad Shepherd biting beer cans in half up against the stage at the Paddington Town Hall; big holes in the low fairy light studded ceiling just above Tony’s spot at a venue called the ‘Talking Tables’, Brett’s winkle picker-clad feet entwined with a pair of stilettoed fish netted feet protruding from under the toilet door at the Strawberry Hills/Southern Cross; Boris and I rabbiting on with amphetamine-fuelled drivel into the night leaving for Sydney in our friend Peter Simpson’s Commercial van after conquering Collingwood’s ‘Tote’ Hotel one more time; James Darroch dancing his arse off and looking very Mickey Dolenz-like up the front at the Vulcan; Ron Peno mocking and admiring us with in a tarty red wig: and last but certainly not least, a floor full of gyrating punters lifting off the ground in unison, each trying to out do his or her neighbour just as the loud bit of We Had Love kicked in.

8. 1984 – UK AND EUROPE

At the time, it seemed as if none of us did anything for the first year in the UK but stand in queues and pay exorbitant VAT- inflated prices when we got to the end of them. In retrospect, and at the risk of boasting, I can only be amazed at how far we got in that small amount of time. Firstly, we had a local release for Blood Red River on Rough Trade. Next we virtually walked into All Trade Booking Agency and got a whole stack of shows at places like Dingwalls, The Electric Ballroom, The Lyceum and The Clarendon Garage. As well, Tony and I rather cheekily wrote Kid Congo a letter telling him we were going to support the Gun Club on their UK tour. There was no talk of this with the agency – we just did it ‘off the bat’ and that seemed to clinch it taking care of exposure over the rest of England for us. The next step was for the Dutch fellow previously mentioned to walk in to All Trade and see our photo and then book us into ‘Futurama’ in Belgium and the ‘Pandora’s Box’ festival in Rotterdam. At ‘Pandora’s Box’ we found ourselves in front of a huge jampacked room which moved back a full metre the moment we launched into our set. After that we got our picture taken a lot and I ended up having to do loads of interviews for foreign mags that I would never be able to read unless they were in the three sentences of Deutsche that I know. As Boris pointed out to me, this gig set us up for Holland and Belgium over the next couple of years. It wasn’t long after these festivals that we made it to Paris and then Hamburg.

Back in the UK, our audience at this stage was comprised partly from the network of Cramps and Gun Club fans who had been alerted to our existence by the tireless efforts of Scotsman and Next Big Thing writer Lindsay Hutton and partly from a curiosity amongst punters as to what kind of act could draw the particular kind of adjective from the ink of the three British trade papers, NME, Sounds and Melody Maker, that we did. I was quite happy at that stage of my life to be referred to as the “lowest form of uncaring anti-social filth” in what amounted to a music tabloid with a circulation of hundreds of thousands so long as they meant we were great. We got quite a bit of coverage and most of it was positive in that kind of way. At Pandora’s Box a Belgian chap called Paul Delnoy asked if he could make a record with us on his label. He did not seem to have enough English to understand ‘no’ (we were tied up contractually) which is why we ended up in Brussels at the end of the year trying to make up another record from scratch that didn’t overlap with the material we were working on for our next proper album.

We were there a week in Paul’s studio and the usual scenario went like this:

Me: “What’ll we play guys? That thing I showed you last week or shall we jam on something new?”

Tony: “I don’t ‘jam.”

Brett: “I’m feeling concave. I need a burger.”

Boris: “Get the guy a burger. I’ll have one too.”

Tony: “Does it have to be a burger? They’ll put onions in mine for sure. They always put onions on when I specifically ask them not to in the English-speaking world so I haven’t got a hope here.”

One hour later, after everyone has eaten:

Brett: “I’m too stuffed to play. Let’s go to a bar.”

For about half an hour of that week the band managed to be in the mood to play something and the tape happened to be running. It was rough as buggery but in my humble opinion there was enough power and feeling committed to tape in that time to make up for the rest of the dicking around. That session became the Demolition Derby 12 inch.

Images I have in my mind from the time are: Peter Weening from the Vera in Groningen with loads of plastic bags full of Indonesian takeaway for us to eat on our first visit, our next visit and the one after that (and hopefully my next visit – it wouldn’t be the Vera otherwise); Boris, in a fit of pique, smashing up his amplifier into pieces so small they could fit into a jar backstage at the ‘Opera Night’ gig in Paris; Tony’s account of an elderly concierge lady bursting into his room with a blow torch to thaw out the pipes; endless riders of Grolsch; endless ratatouille provided by a procession of Dutch and Belgium promoters; standing behind Joe Strummer every week in the Barclays Bank queue watching him deposit thousands of pounds at a time; the rabbit warrens a band had to find its way through to get to the stage at those bigger London venues just like in Spinal Tap; and Boris, Tony and I getting into a fight with some abusive Dutch yobs who persisted in calling us kangaroos outside the Melkweg in Amsterdam. These ‘yobs’ turned out to be the club bouncers and we ended up being turfed out onto the exit bridge in the middle of the snow whilst having the fire hoses turned on us. I still have the burgundy satin shirt with it’s ripped tail from that incident.

This is how I remember some of what happened to me, Boris Sujdovic, Tony Thewlis and Brett Rixon as members of The Scientists from the beginning of 1982 to the close of 1984.

The Martin C who doesn't clean out squat toilets

May 3, 2010 at 10:04 pmYES! The Scientists were fucking brilliant (though I think their two greatest moments were ‘Swampland’ and ‘Atom Bomb Baby’). Thanks for posting this.

Mark

May 5, 2010 at 12:10 amI got my copy of “This heart doesn’t run on blood…” for 50p when the local record shop shut down in the mid 1980s.

It took me a long time to meet anybody else who liked The Scientists – a few acquaintances had booed them at Banshees and Sisters Of Mercy gigs, I used to use that 12″ to get people to leave my house when it was getting late…

pOoTer

May 20, 2010 at 3:04 pmSaw them countless times and loved them big time, still play their records today and rate them highly. The Hammersmith Clarendon (RIP) was the fantasticly filthy shithole (best small venue in London I always say !!!) where I saw them the most, sweat running down the walls, people sprawled all over the stairs, the floor flexing, toilets awash with detritus and piss and these guys on stage, heads down, legs astride and giving it some……..amazing and never forgotten 🙂